Five episodes that showcase some of Mad Men’s major minor players

In 5 To Watch, five writers from The A.V. Club each make the case for a favored episode from a favorite show. The reasons for their picks might differ, but they can all agree that each episode is a must-watch. In honor of Mad Men Week, in this installment: We each picked an episode featuring a minor but key character in the Mad Men cast.

Yes, Mad Men is mostly about Don Draper, but it’s not all about Don Draper. As magnificent as Jon Hamm is, the show would not be as enjoyable without the vast cast of characters that surround Don, from coworkers to his family to his relationships to neighbors. Below we’ve picked five of our favorite minor Mad Men players and the episode that perfectly spotlights each one of them. In the richness of the Mad Men universe, even Miss Blankenship gets a moment to shine.

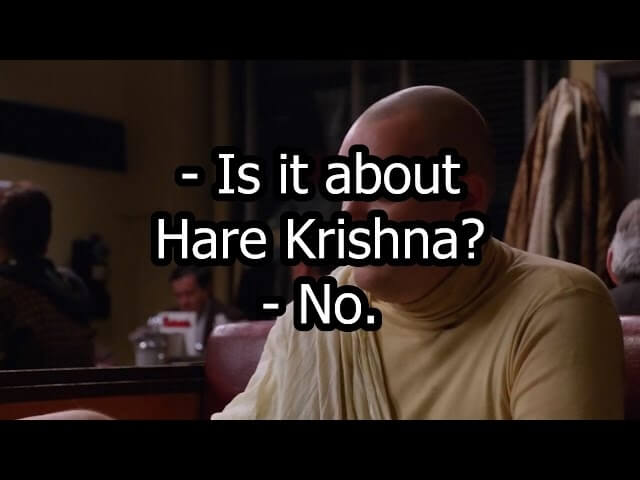

Erik’s pick: Paul Kinsey, “Christmas Waltz” (season five, episode 10)

Prior to getting ground up in the “Shut The Door. Have A Seat” bloodbath, Paul Kinsey was Sterling Cooper’s man of a thousand affectations. The beard, the pipe, the black girlfriend he showed off like an accessory—even in a world of stuffed shirts, Paul’s had the least substance behind it. But he longed for substance, which explains how he’d wind up sucked into that ultimate net for lost souls of the ’60s, the International Society For Krishna Consciousness. Simply dressing Michael Gladis in Hare Krishna garb is enough for a punchline in “Christmas Waltz,” but the bittersweet satire hiding among season five’s more wicked surprises hones in on the person beneath the sikha, the guy who’s still as anxious, insecure, and terrified of living life as he was when he dropped a Twilight Zone allusion into Peggy’s first tour of the office. He’s since moved on to Star Trek (and written a spec script to go with that new obsession), and is sent on the path to new writerly pretensions with a generous Christmas gift from Harry Crane, one of the pretenders who stayed behind while Paul sought enlightenment.

Libby’s pick: Miss Blankenship, “The Beautiful Girls” (season four, episode nine)

Although Mad Men was forever populated with quirky background characters that could be the center of their own shows, this was particularly true for veteran secretary Ida Blankenship. Arriving on the scene in season four, Blankenship served as the antithesis of the typical Mad Men secretary, a fact that made her a perfect match to work Don’s desk in the wake of his troubled history with secretaries. Brilliant comic relief as portrayed by Randee Heller (who earned an Emmy nomination for the role), Blankenship was the opposite of a fish out of water. She was big, it was the office that got small. With her history as Bert Cooper’s longtime secretary and historical fling with Roger Sterling, who remarked in his taped memoirs that she was the “Queen Of Perversion,” Ida was a magic mirror held up to the face of every woman working at Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce. She used to be just like them. Soon they’ll be just like her. Blankenship may have been comic relief, but time always gets the last laugh. In “The Beautiful Girls,” an episode about the trials of womanhood at every juncture in life, Ida Blankenship offers her usual hard-hitting wisecracks, helping Bert with a crossword puzzle, correctly pegging Peggy as a masochist. But by the end of the episode, Miss Blankenship exits this world as she lived in it, sitting at her desk, outpaced by the world to which she’d given her livelihood. In the end, she served not only as a perfect character, but a perfect portent for those who outlived her.

Alex’s pick: Glen, “New Amsterdam,” (season one, episode four)

For an episode that’s largely memorable as the introduction of one of Mad Men’s oddest little characters, “New Amsterdam” is shockingly light on Glen (Marten Holden Weiner). The young son of the Drapers’ recently divorced neighbor Helen Bishop, Glen is a sporadic but indelible minor character. After getting roped into babysitting one night, Betty Draper heads to the Bishop house and meets the series’ strangest young character. Upon re-watching the episode, what’s amazing is how little time is spent with Glen. When she first arrives, Glen is playing the piano, normal as normal can be. But it’s Betty’s trip to the bathroom that unleashes Glen’s inner weirdo, as he insists on walking in on her in the bathroom. Betty is furious, of course, but her scolding of Glen quickly gives way to support when his tears and spontaneous embrace seem to jar her into a sense of…kinship? Affection? It’s unclear, like many of Betty’s emotions. But what’s not the least bit debatable is that Betty, after Glen compliments her hair and asks for a chunk of it, stands up, grabs a scissors, and cuts off a lock of hair—with almost no hesitation. This amazing scene helped clue the audience in to just how closely below the surface Betty’s buried qualities lay. Glen represents a break from the expected for the Draper women, first with Betty, and later with Sally. These two short scenes in “New Amsterdam” dominate the whole episode—and like many future scenes, the magical oddity that is Glen holds sway, delightfully so.

Kayla’s pick: Megan, “A Little Kiss” (season five, episode one)

When Don Draper proposed to his assistant Megan (Jessica Paré) at the end of season four, we knew very little about this woman and where exactly the show could go with a new Draper marriage. “A Little Kiss” is Megan Draper’s true character debut and a very clear signal that Don’s new relationship would be just as toxic as his marriage to Betty, but for very different reasons. Megan is the first woman in Don’s life to match his desire for control. When she throws him a birthday party in the fifth-season premiere, Megan moves throughout the room in her sheer sleeves and winged eyeliner, catching the eyes of most of the mixed company in attendance. Then she very intentionally demands for everyone to look at her when she takes the stage to give a sexy yet fraught performance of “Zou Bisou Bisou,” aimed directly at a very embarrassed Don. Commanding the attention of a room is Don’s job, but beyond shifting that power dynamic, Megan also pokes at her husband’s greatest fear by breaking his privacy wall. “Zou Bisou Bisou” is the first of many power plays by Megan throughout her marriage to Don, which sits in the spotlight of the fifth season. The surprise performance allows Megan to freely express her sexuality in front of Don’s coworkers and friends, showing them all that she’s her own woman, with her own personality, and not just some extension of Don’s dreams and desires. And on top of all that, the song is just catchy as hell. Megan Draper should drop a mixtape.

Gwen’s pick: Sal, “The Gold Violin” (season two, episode seven)

Of all of Mad Men’s now-departed characters, Sal, played by Bryan Batt, is one of the most-missed, as a gay man trapped in a world of heterosexuality. In the sexist offices of Sterling Cooper, Sal stood out with his compassion, his manners, his reluctance to degrade women, and the fact that he lived with his mother and spoke Italian (no wonder he was the subject of so many secretary crushes). But Sal finds it difficult to get ahead, is propositioned by clients and bellboys, tries to force some affection for his wife, and eventually loses his job after he refuses the advances of Lucky Strike’s Lee Garner Jr., following the two worst words Don Draper ever said (or sneered): “You people.” No episode painfully depicts Sal’s plight like “The Gold Violin,” when Sal and Ken from Accounts find that they have similar artistic leanings. Ken then gives Sal his new short story to read: “The Gold Violin” of the episode title, referring to a beautiful instrument that can’t be played. For Sal, Ken is the unattainable gold violin, and his admiration for his coworker only increases when he and his wife have the bachelor over for dinner. As the two men meet on every level but a crucially important one, Sal ignores his wife and cherishes the lighter Ken leaves behind. The openly gay Batt masterfully depicted Sal’s unrealized longing. His ultimate fate was left up in the air, but hopefully Sal fared better in the post-Stonewall, slightly more progressive ’70s.