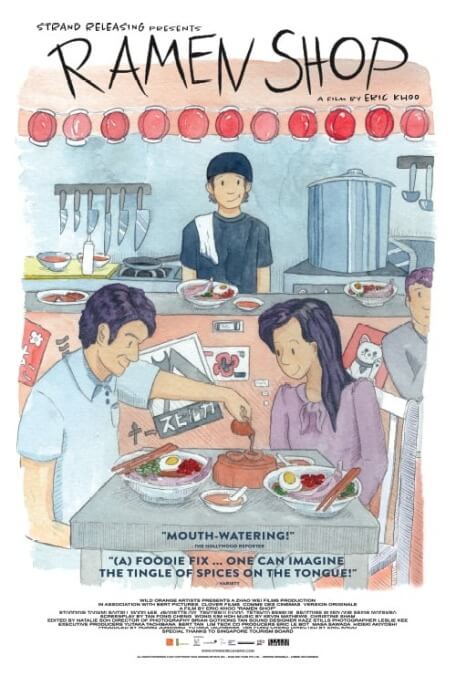

Food, family, and history combine in the sweet, thin broth of Ramen Shop

Food is one of the most powerful emotional forces on Earth. For many people, the smell and taste of a favorite childhood dish brings back vivid, nostalgic memories of a particular moment in time, often a moment when that person felt safe, content, and loved. For Masato (Takumi Saitoh), the half-Japanese, half-Singaporean protagonist of Singaporean director Eric Khoo’s Ramen Shop, the desire to recapture just such a moment becomes an all-consuming quest after his emotionally distant father literally dies doing what he loves: preparing for another day of work at the family ramen restaurant in a small Japanese town.

Food is also a great unifying force, with the ability to bring together people who otherwise have nothing in common. Cross-cultural communication is another important component of Masato’s quest, which takes him to Singapore to meet his estranged uncle, Ah Wee (Mark Lee). Masato’s mother, who died when he was just a kid, was disowned by her family for marrying a Japanese man, leaving her son with little more than a book of recipes handwritten in Mandarin and an intense longing to reconnect with the Chinese part of his heritage. Being a foodie type, he naturally seeks to do this through cooking—specifically, by asking his uncle to teach him the recipe for Bak Kut Teh, a Singaporean pork-rib soup served with its own special tea. Despite the fact that the men can only communicate in elementary English, Ah Wee agrees.

In press notes for Ramen Shop, Khoo cites being “crazy about good food” as a common thread between Japanese and Singaporean culture. (Japan, in particular, is known for its nigh-pornographic food TV.) The film, in turn, is permeated with passion for all things edible, frequently stopping for travel-series-worthy close-ups of chefs preparing toothsome delights like chili crab, fish head curry, and pork ramen. There’s even a supporting character, Japanese expat and food blogger Miki (Seiko Matsuda), whose primary purpose seems to be to go out with Masato and explain what they’re about to eat as the camera lingers lustfully. Mixed in with footage of Singaporean tourist attractions, Ramen Shop doubles as a travelogue. And that’s just as well, given that the drama portion of the film is slight, even when accounting for the heavy history behind why Masato’s elderly grandmother Madam Lee (Beatrice Chien) hates Japan.

That being said, no foreknowledge of the Japanese occupation of Singapore during WWII is necessary to understand Ramen Shop. And, in a testament to Khoo’s skill as a director, a brief detour to a museum exhibit explaining the horrors of the war only temporarily brings down the overall light mood. What may be harder for foreign audiences to digest is the film’s naked sentimentality, a trait that caters more to East Asian cultural tastes than Western ones. But if you can tolerate a little saccharine piano music and ethereal backlighting with your food porn, Ramen Shop is an appetizing little bite of multicultural foodie edutainment.