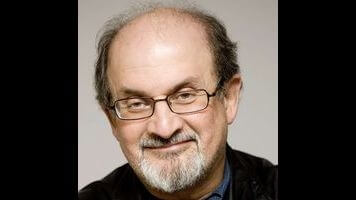

For a fantasy fable, there’s little fantasy and no fable in Salman Rushdie’s latest

Genre fiction has always been poking around the mainstream, but now more than ever it’s enjoying unprecedented success. Sci-fi and historical fiction, fantasy and bawdy romance, superheroes and dragons, are an integral part of the mainstream media diet, be it in literature, television, or film. Perhaps it’s no surprise that fantasy and sci-fi are enjoying widespread appeal. After all, most can relate to the way those genres explore class division, oppression, economic and moral collapse, and the constant fight between good and evil. Such themes feel particularly relevant and urgent in 2015, and the best fantasy and sci-fi writing isn’t an outlandish exploration of the future or some magical past, but a insightful examination of our current culture.

Salman Rushdie’s latest novel, Two Years Eight Months And Twenty-Eight Nights, is a fantasy fable, or at least its evocation of magic, colliding worlds, and sprawling timelines suggest that it is. Two Years largely tells the story of a jinn named Dunia. The jinn or jinni are “creatures made of smokeless fire”—which is Rushdie’s way of using flashy rhetoric to overcome the lack of mythology built into the story—and Dunia is one of their princesses. In the 12th century she falls in love with a human philosopher named Averroes, also known as Ibn Rushd (wink wink), and produces multiple jinni children. Those children, the Duniazát, disperse across the Earth and eventually lose touch with their roots and propensity for the supernatural. Much later, in contemporary New York, a great storm leaves many people with unexplained powers. There’s Mr. Geronimo, whose feet no longer touch the ground, and a baby nicknamed Storm Doe who ends up on the steps of City Hall and can sense which city officials are corrupt.

The line that separates the human world from that of the jinni is split open during the Storm, and a battle that’s been brewing since Dunia’s time is once again renewed. It’s a fine if unnecessarily elaborate setup, but the inventiveness stops there. It’s not so much that the tale is familiar and contrived, despite pulling from more Eastern influences, but that the prose and storytelling conflates detail with depth. Two Years is a wordy novel, and the result is not an elaborate text of interweaving stories and a rich tapestry of mythology, but rather a paint-by-numbers approach to world building. When Rushdie details the dark forces that Dunia and her cross-generational brood must go up against—Zumurrud, Zabardast, Shining Ruby, and Ra’im Blood-Drinker—the long-winded descriptions are often silly, and always frustratingly forgettable.

Essentially, Two Years thinks that the allure of fantasy fiction is the lengthy descriptions of attire, families, worlds, and philosophies. While that’s certainly part of the appeal, what grounds the elements of magical realism is the humanity at its core, and it’s a lack of humanity that makes Two Years feel so uninspired. Mr. Geronimo, like every other character in the novel, is defined by his new supernatural abilities and nothing else. The novel is filled with such glib, shallow characterizations.

More than just a mess of tired genre tropes and self-satisfied prose, Two Years ultimately fails because it’s fashioned as a fable but is unsure of its overarching lesson and never truly identifies the object of its scorn. Two Years touches on a number of interesting themes, from the tension between religion and rationalism, to issues of immigration, globalization, and the way in which capitalism runs contrary to the needs of the planet. Such themes are hastily explored, though. Rushdie’s inability to craft a compelling and perceptive underlying theme is indicative of the thematic and emotional emptiness of the novel as a whole.