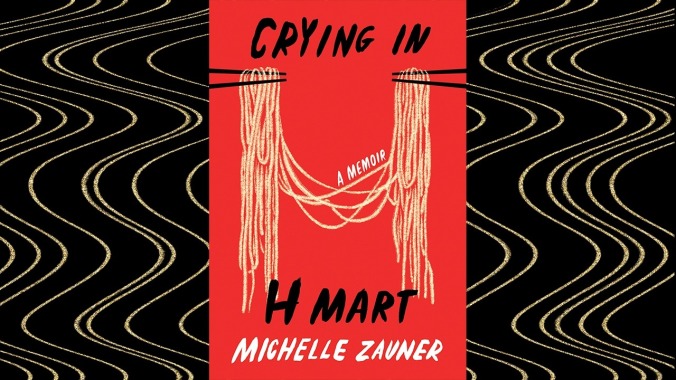

For Japanese Breakfast’s Michelle Zauner, food is both comfort and connection in Crying In H Mart

“Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart.” Wandering the aisles of the pan-Asian grocery store, Michelle Zauner sees the specter of her mother. She cries when she can’t remember which seaweed brand her family used to buy, and she cries seeing a Korean grandmother in the food court, picturing how her mother would’ve aged had she lived into her seventies. Representing “freedom from the single-aisle ‘ethnic’ section,” H Mart’s abundance of instant noodles, banchan, and snacks adorned with cartoons becomes an anchor to Zauner’s heritage. She writes, “I can hardly speak Korean, but in H Mart it feels like I’m fluent.”

As with Zauner’s viral New Yorker essay of the same name, Crying In H Mart is a heartfelt, searching memoir of a mother-daughter relationship prematurely ended by cancer. Zauner, the indie rock musician who performs as Japanese Breakfast, reflects on summers spent in her birthplace of Seoul and life as an only child in Eugene, Oregon. Her mother—adventurous in travel and appetite, yet strict at home—is an object of her obsession, and Zauner spends her childhood desperate for her mother’s affection yet intent on flouting her many rules.

A fissure forms in their relationship when an adolescent Zauner discovers music, which her mother sees as frivolous, and she runs away at the end of high school. Despite mending things with her mother in early adulthood, Zauner feels lingering guilt over what she considers her own ingratitude. After learning of her mother’s stage IV squamous-cell carcinoma diagnosis, Zauner moves back home, intent on becoming the perfect daughter as atonement. Living under her parents’ roof again revives dormant feelings of inferiority. Like many diasporic and biracial people, the Korean American Zauner alternates between pride and shame over her culture.

Zauner’s storytelling—and recall of her past—is impeccable. Memories are rendered with a rich immediacy, as if bathed in a golden light. As she and her mother drive from the infusion clinic singing Barbra Streisand songs while the sun sets, the clouds are “flushed with a deep orange that made it look like magma.” Zauner is also adept at mapping the contradictions in her relationship with, and perception of, her mother. While writing her mother’s eulogy, she feels conflicted over the idea that she may only be remembered as a mom and housewife. “Perhaps I was still sanctimoniously belittling the two roles she was ultimately most proud of,” she writes, “unable to accept that the same degree of fulfillment may await those who wish to nurture and love as those who seek to earn and create.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.