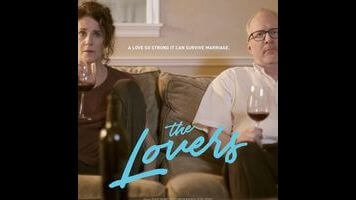

For the dead-end couple of The Lovers, even breaking up is a compromise

Azazel Jacobs’ The Lovers is set in the sort of unremarkable, average, suburban America that is rarely depicted in American movies in anything but a negative light, usually as a place where dreams go to die. So one of the unexpected virtues of this small, thoughtful film is how it resists treating these surroundings as soul-crushing or as a symbol of the failure of middle-class mores, all while telling a story about disaffection and the yearning to escape—a ballet of ordinariness that uses a nostalgic, waltzing score (by longtime Jacobs collaborator Mandy Hoffman) to reveal the internal melodrama of middling lives and longings. Its central characters, Mary (Debra Winger) and Michael (Tracy Letts), are fiftysomethings whose dull marriage reached a dead end long ago. Both are carrying on affairs—she with writer Robert (Aiden Gillen), he with dance teacher Lucy (Melora Walters). And just as they are about to finally leave one another for their respective paramours, they find themselves re-sparking their relationship. Jacobs—who had an indie breakthrough with Momma’s Man, but hasn’t directed a feature since Terri—gives the movie the classic structure of a comedy of remarriage, pulling off an apt ending that transcends irony without exactly transcending the film’s badly strained third act.

Despite the implied symmetry (two quasi-bohemian lovers, a reversal of attractions, etc.), much of what makes The Lovers so compelling is the way it observes the differences between Mary and Michael, two people who are escaping the same marriage in the same way for different reasons. Besides being a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright (adapted in the likes of August: Osage County, Killer Joe, and CBS’ Superior Donuts), Letts is an accomplished actor, and in his first film leading role, he brings a wonderful believability to Michael’s pathological detachment as well as his mundane habits. (His loud, over-emphatic “phone voice” is a great character detail in itself.) One quickly gets the sense of a man who longs for self-determination, but can only understand it in terms of relationships and responsibilities—a man who lies to both his wife and his mistress. He feels oppressed and burdened by others, but, given the free time, would probably do nothing. In subtle contrast, Winger finds in Mary a touch of unglamorous, inhibited sensuality; it’s a very perceptive performance, but because Mary is the more easily relatable and less contradictory character, she comes across as less dramatically compelling.

Her dilemma is her rekindled attraction to Michael; Michael’s dilemma is his reluctance to either commit or let go of both Mary and Lucy. She might love both of the men in her life, and it’s possible that he doesn’t really love either of the women in his. Or, to put it another way, she’s looking for pleasure while he needs to please, and the simple truth is that these aspects of their personalities aren’t complementary, but are in fact incompatible. If there’s a broader theme that Jacobs is trying to develop here, it’s that every relationship involves a compromise. (However, he never questions the relationship between Mary and Robert the way he does Michael and the lonely, short-tempered Lucy.) Employing a clean camera style, he treats the office parking lots, dens, and kitchens where so much of the movie unfolds as intimate blank spaces—beige boxes, akin to the classic black-box stage of a small theater, with Hoffman’s score as the counterpoint that, like a play, asks the audience to imagine what the characters see. The Lovers isn’t a movie of flashy camerawork; in keeping with its air of banality, the closest thing to a stylized camera movement introduced by Jacobs and director of photography Tobias Datum involves specks of dirt on a mirrored closet door.

But the low-key pragmatism sours into staginess with the climactic arrival of Michael and Mary’s temperamental college-age son, Joel (Tyler Ross), who comes to visit with his girlfriend (Jessica Sula). Voices are raised, teeth are gnashed, fingers are pointed, and a wall is punched through. One might read Joel, the product of this largely loveless marriage, as an angry, accusatory manifestation of all of its wrongs. But just as Michael and Mary only rediscover their attraction to each other when it becomes illicit—when they’re so emotionally involved in their affairs that sleeping with each other qualifies as cheating—The Lovers can only find a memorable expression for its characters’ complicated and conflicted feelings when they are unspoken and hidden behind facades of suburban boredom. The noise doesn’t amplify the movie’s most suggestive qualities. It drowns them out.