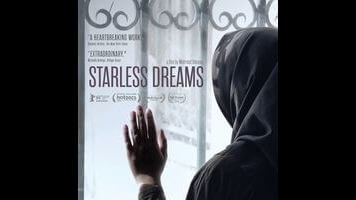

There’s nothing especially new about jailhouse confessionals. What sets Starless Dreams apart are the particulars of who these crooks are. They’re Iranian teenage girls, living in a stark Tehran dormitory while awaiting word from the authorities about when they’re going to be sent home. They don’t seem to know much about the vagaries of the Iranian justice system, but they do know that life on the outside has for the most part been worse for them than life behind bars. So there are curious wrinkles aplenty in Starless Dreams, from how reluctant the prisoners are to be set free to the way Oskouei’s camera lingers on sweet-looking young faces—framed in head scarves—as they talk about their pimps and pushers.

Iranian cinema’s reputation for sensitive, socially conscious neorealism has its roots in the country’s strong documentary tradition. Directors like Jafar Panahi and the late Abbas Kiarostami (the latter of whom made a handful of great docs himself) have often spoken about being influenced as much by nonfiction filmmaking as they were by classical drama and the avant-garde. The impulse of artists like Oskouei is both journalistic and empathetic. They want to take their viewers inside parts of their homeland that they generally avoid and ignore, forcing them to see poverty and desperate behavior as something other than remote problems, best understood through the twin lenses of politics and religion.

For American audiences, films like Starless Dreams can be even more revelatory, since we see so little of Iran beyond cable news images of angry mobs. Outside of the hijab, the girls in this movie don’t really fit any of the stereotypes of Iranians in the U.S. media. They come across like teenagers in any modernized country: alternately silly and moody, and preoccupied with boys and pop music. A lot of what happens in Starless Dreams could just as easily have been shot in some suburban U.S. high school. The kids spin a Sprite bottle to play Truth Or Dare. They greedily devour pizza. They get a lecture on AIDS from a health teacher and receive spiritual guidance from a religious leader who’s more condescending than helpful. They commandeer Oskouei’s microphone to sing songs and then playfully mock him by pretending to interview each other the way he interviews them.

It’s hard to say what’s oddest about Starless Dreams: that these girls are leading very ordinary-seeming lives while in prison or that they’re doing it in a prison in Tehran. Either way, Oskouei strikes a balance between the unfamiliarity of the location and the relatability of his subjects. In between the prisoners sharing their personal histories, the film shows them in supervised visits with the children they had very young and observes them as they deal with the peculiarities of their circumstances—as in one scene in which they bring in laundry that has frozen on the courtyard drying line in the dead of winter. Everything here is at once mundane and strange.

What distinguishes Starless Dreams is Oskouei’s voice, heard from off screen, getting these girls to be honest about where they’ve come from and why they’re less than anxious to return. He lingers over their scarred arms and hands and gets them to admit that they have family members who’ve beat them, raped them, drugged them, and sold them into prostitution. These details are heartbreaking, and yet the saddest moment in the entire film comes when one prisoner chides Oskouei for telling them he has a 16-year-old daughter. For a lot of the kids, it’s easier to believe that they’re bound by a society that’s stacked against them and everyone they know. To hear that some teens in Iran lead better lives is almost cruel. That’s another of this movie’s many poetic ironies. The people watching it need to see more of our planet’s rich variety. The people in it would rather keep their own worlds small, and locked.