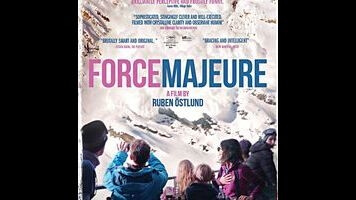

Force Majeure is a darkly comic study of male ego in collapse

For a fleeting moment, one could reasonably mistake Force Majeure for a disaster movie. Certainly, its characters might wonder, through their panic and fear, if they’ve somehow stumbled into one. The pivotal scene arrives early, on the second day of a blissful family vacation. Seated for a relaxing lunch on the terrace of a French ski resort, married Swedish parents Tomas (Johannes Kuhnke) and Ebba (Lisa Loven Kongsli) are alarmed by the rapid approach of snow, tumbling down the adjacent slope in their general direction. As the wall of white seems to close in on them, expanding outward with menacing speed, Thomas makes an instinctual flee for safety, completely abandoning Ebba and their two young children. The avalanche, as it turns out, is controlled; what looks like certain doom is just a false alarm, a dramatic billow of powder. But as the smoke clears, so too does any illusion Ebba might have held about Tomas and his paternal instincts. There’s no going back from such a flagrant act of self-preservation, however involuntary it might have been.

Force Majeure, in other words, is a kind of disaster movie, one in which buildings are left standing while a marriage—and a fragile masculinity—buckles at its foundation. The film’s director, Ruben Östlund, ticks down the aftermath in days, showing how Tomas’ failure of nerve—which he vehemently denies for as long as possible—reverberates through every subsequent scene. Ebba, frustrated by her husband’s refusal to own up, begins confronting him about it in mixed company, turning polite dinners into gauntlets of social awkwardness. (In a particularly shrewd touch, many of the bystanders to these spats rationalize Tomas’ actions, even as they assure themselves that they’d respond differently.) The film recognizes a fundamental split in how its protagonists approach what happened: For Tomas, skirting personal responsibility is a way to avoid thinking of himself as a coward; for Ebba, the problem runs much deeper. How can she love a husband who would leave her, and their children, to die alone? (A mid-film monologue eloquently addresses that question, the film earning points for delaying the inevitable cut from Kongsli’s poignant delivery to her co-star’s sheepish reaction shot.)

Many have compared Östlund to famed Austrian scold Michael Haneke, with whom he shares a command of escalating tension and a chilly formal control. But whereas Haneke hasn’t a funny bone in his body, Östlund locates a fair amount of black humor in the material. The acting helps: Kuhnke, in a superbly funny performance, gradually reveals the pitiful, wounded pride beneath his character’s defense mechanisms. But the unlikely comedy is also built into the structure of the movie, which allows for a brief but inspired switch in perspective when the tension between Tomas and Ebba seems to pass like a virus to another couple. Furthermore, Östlund earns laughs through sly sideline details: a gruff janitor who seems to always be watching, judgment and accusation inherent in his silence; a strategically placed chicken sticker; a remote-control toy that creates a tension-breaking punchline.

At its core, Force Majeure is about the false equilibrium gender roles sometimes create in relationships, and what can happen when that balance is disrupted. The film smartly teases such interests in its opening scene, in which Tomas, Ebba, and their adorable moppet kids awkwardly pose for a pushy photographer, looking like some model of the traditional, nuclear family. If there’s any fault to find in this expertly directed, frequently hilarious study of imploding male ego, it’s that Östlund basically arrives upon a perfect ending—one that brings the movie full circle, both dramatically and visually—and then bypasses it in favor of a more muddled one. But as climactic missteps go, it’s not exactly disastrous.