Fort Tilden is a funny and compassionate skewering of millennial culture

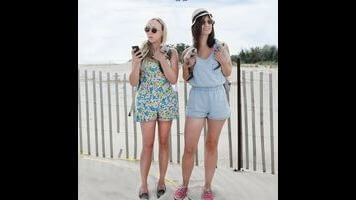

“It’s authentically distressed,” says Allie (Clare McNulty) of the barrel she and her friend Harper (Bridey Elliott) find lying in the sand near the end of Fort Tilden. Like so many lines in Sarah-Violet Bliss and Charles Rogers’ caustic comedy, it’s a sharply double-edged observation. Not only is the chipped wooden container in question more genuinely weathered than the one the women had already purchased as a conversation piece before beginning their trip to the beach, but Allie’s observation also stands as a piece of inadvertently pointed self-analysis.

Harper and Allie are indeed damsels in distress, and not just because they can’t efficiently navigate the way from a Brooklyn loft to the Rockaways (a disastrous, distended day trip to hook up with some boys, which makes up the film’s entire plot). They’ve been shaped by a parentally subsidized lifestyle that permits neo-bohemian arrogance without the threat of actual starving-artist poverty; their family ties simultaneously insulate them from harm while rendering them defenseless against the smallest challenges to their egos and routines. Far from the exercise in vicarious hipster-voodoo-doll skewering its basic setup suggests, Fort Tilden is at once less sentimental and more incisive about privilege and its discontents than the recent films of Noah Baumbach.

It’s also funnier. The screenplay’s numerous running jokes are thoroughbreds, starting with Allie’s post-graduate plans to join the Peace Corps in Liberia (“That’s the worst place in the world” says one helpful friend). Instead of merely needling their heroines’ aspirations (Harper claims to be a “mixed-media” artist despite never producing any work) Bliss and Rogers try to penetrate their perfectly appalling exteriors. The point isn’t that these status-conscious, endlessly texting fashionistas are shallow, but rather that their rather remarkable narcissism and strident self-pity are bound up in a bone-deep insecurity—the kind that even audience members who will hate the characters from the word go might just find relatable.

This is not to say that Fort Tilden goes easy on its characters. One of the script’s structuring motifs is that Harper and Allie end up throwing out every item they acquire over the course of the film, culminating in an absurdly awful bit of business involving a litter of stray kittens. (Though it’s a measure of the film’s intelligence that it’s possible to see these lost little furballs as analogues for the human characters who discover them rather than their victims.) Even when Bliss and Rogers stray perilously close to the edge of generational portraiture—the sort of urban-ethnographic satire practiced weekly on Girls—they manage to keep things specific and complex, aided by their stars’ expertly modulated double act. A long interlude featuring four topless female characters offers up the sort of smartly confrontational staging that Lena Dunham often attempts but only rarely brings off.

The idea of literally and figuratively exposing Harper and Allie in the final scenes might not be subtle, but it’s still effective—a sight gag with some bite. For all its exquisite theater-of-cruelty viciousness, Fort Tilden is finally a work of empathy about people whose own supplies are running on empty.