Four Columbia House insiders explain the shady math behind “8 CDs for a penny”

In entertainment, an awful lot of stuff happens behind closed doors, from canceling TV shows to organizing music festival lineups. While the public sees the end product on TVs, movie screens, paper, or radio dials, they don’t see what it took to get there. In Expert Witness, The A.V. Club talks to industry insiders about the actual business of entertainment in hopes of shedding some light on how the pop-culture sausage gets made.

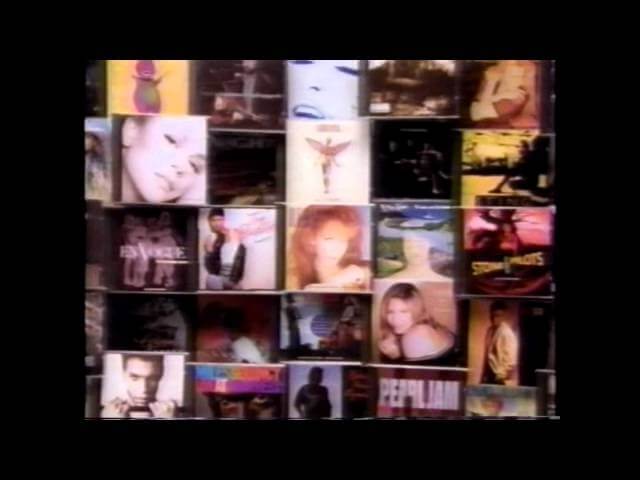

Any music fan eager to bulk up their collection in the ’90s knew where to go to grab a ton of music on the cheap: Columbia House. Started in 1955 as a way for the record label Columbia to sell vinyl records via mail order, the club had continually adapted to and changed with the times, as new formats such as 8-tracks, cassettes, and CDs emerged and influenced how consumers listened to music. Through it all, the company’s hook remained enticing: Get a sizable stack of albums for just a penny, with no money owed up front, and then just buy a few more at regular price over time to fulfill the membership agreement. Special offers along the way, like snagging discounted bonus albums after buying one at full price, made the premise even sweeter.

By the mid-’90s, too-good-to-be-true deals such as eight (or more) CDs or 12 cassettes for a penny had codified into pop culture lore. So what if these CDs were way more expensive than ones purchased in stores, after factoring in shipping? After all, gaming the system by joining under fake name(s) or addresses—or sending back unwanted albums or accidental orders by scrawling “return to sender” on the box in which they arrived—was a snap. Whether buyers were allowance-challenged, wanting to replace fusty vinyl with shiny plastic CDs, or simply not within driving distance of a store that sold music, Columbia House was clearly addressing consumer demand.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, record clubs such as Columbia House (and its rival, the BMG Music Club) were an incredible driver of CD sales: In 1994, 15 percent of all discs in the U.S. sold because of these clubs, while a 2011 Boston Phoenix article, “The Rise And Fall Of The Columbia House Record Club—And How We Learned To Steal Music,” reported that 3 million of the 13 million copies sold of Hootie And The Blowfish’s Cracked Rear View were sold this way.

Filmmaker Chris Wilcha captured what it was like working at Columbia House during this boom time in a low-key, first-person documentary called The Target Shoots First. Wilcha—who started off in the marketing department as an assistant product manager and was soon promoted to product manager—took a camcorder to work and captured the absurdity and mundanity of the company at that moment in time. He filmed scenes not just in the company’s New York offices, but also at the massive Terre Haute, Indiana, manufacturing, customer service, and distribution center (which employed 3,300 people in 1996) as well as an amusing Aerosmith in-store appearance and a trade-show rendezvous with David Hasselhoff.

Incredibly, few people seemed to bat an eye at the camera, which allowed Wilcha to capture the weird tension between the freewheeling creative department and responsibility-burdened marketing team, the old-guard music executives and the younger employees versed in the nascent alternative music culture, and a corporate environment not quite sure what to do with the next generation. Today, Wilcha, who co-directed Knock Knock, It’s Tig Notaro and directed/co-executive produced Showtime’s version of This American Life, calls The Target Shoots First “a weird, pre-internet document of that moment [in time], like The Office before The Office,” which is a good assessment; if anything, it’s an unselfconscious (and often quaint) look at a time just before technology revolutionized both office culture and the music industry.

Twenty years after it was filmed, what’s incredible about Wilcha’s documentary is how the experience of working at Columbia House informs (and, at times, even parallels) the modern media landscape. That comes up time and again when Wilcha and several of his Columbia House co-workers—former New Yorker pop critic/musician Sasha Frere-Jones, author/teacher Alysia Abbott, and journalist/editor/content strategist Piotr Orlov—hop on a conference call with The A.V. Club for a roundtable discussion. The quartet immediately jumps into conversation, covering the quirks of their time at the company with plenty of laughter (and, on occasion, some cynicism). Each participant in the call had a hand in producing the colorful catalogs that were mailed to members, the ones listing hundreds and hundreds of CDs and cassettes available to purchase in a given month. They also reminisce about all the characters they worked with, including one man (featured in The Target Shoots First) whose windowless office featured stacks and stacks of paper printouts, piled haphazardly on every available surface. That’s the entry point into the below conversation.

On physical media

Sasha Frere-Jones: Compared to what life is like now, every office—there was so much fucking paper everywhere.

Chris Wilcha: Paper and CDs. There were so many objects.

Alysia Abbott: Everything was in material form. It was all this piling up of media, boxes of CDs: The hoarding of CDs that was going on, and the monthly clearing out of CDs from the creative department, and everyone coming around picking through them. It was very weird.

SFJ: It was amazing to think there was a moment when you could be covetous of CDs. It’s such a strange feeling now to think, “Oh man, I think Chris has an extra copy of that Definitely Maybe. Maybe he’ll lend that to me?”

On Columbia House’s parallels with (and differences from) modern music industry innovation

CW: One of my friends who was part of one of these streaming services, he recently asked to see The Target Shoots First for the first time. And I lent it to him, and his mind was boggled by how many of the same issues he was dealing with starting a streaming service.

Piotr Orlov: I too started a streaming service for MTV [URGE], and it was very, very humorous watching everything from metadata to rights. My ability to actually navigate that world in the ’00s, starting URGE and then working for Rhapsody, was helped by the fact I had already done so at Columbia House.

CW: Right. You had to find the voice, and [figure out] how much content are you going to generate versus just being a listing service? Those kinds of questions. But anyway, Sasha, The Target Shoots First showed in Brooklyn about a year or so ago, and [you] very generously set [the screening] up. And one of the things I remember you and I talking about was how the music business back then also had so much fat. Like, Columbia House employing 20 and 30 writers to write the little blurbs. There was this whole fat middle, right? Just how that’s been erased.

SFJ: There’s a lot to talk about in that it mirrors the larger economy… You know, all the mergers that happened at the corporate level are now happening at the musical level. I was talking to someone who was handwringing about Spotify, a fellow musician who wrote an editorial, and when we were talking about the whole thing, he said, “You know, there’s no reason to yell at any particular party, because they all have equity in each other. It’s all one thing, and they’re completely aligned against the artist in every case.”

What we had in the ’90s was… what another very famous, huge record executive [said to me] in a very, very hilarious way. We went to his Fifth Avenue townhouse, gorgeous space, and he said—maybe I’ll give it away if I can do his accent properly—but he said [Affects accent.], “You know what this is? This right here? It’s stupid money. It’s CD money. That’s the kind of money that made dumb people feel smart.” You have the biggest fucking markup in retail history, and somehow in one winter, the music business—with Phillips leading the way—said, “Hey, that $7.99 album you love? Guess what? Your lucky day: You get to buy it for $18.99, it’s going to sound worse, and you have to buy fucking pieces of equipment.” And everyone said, “Great, I’d like to buy more of them please.” And so there was this incredible surplus of money. And then musicians like me [Frere-Jones played in the post-rock/punk-funk band Ui at the time. —ed.] get a day job doing very little at Columbia House, and go on tour, because those jobs existed.

PO: I will also add that’s why when Napster came along, and everybody essentially had a digital master in their home—or hundreds of digital masters in their home—that they could upload very, very easily, I cried not a single tear for those motherfuckers. All of a sudden, by thinking, “Shitty format, we’re going to mark it up 180 percent, and everybody’s going to buy them.” Well, yeah, they did, and they ripped them and decided to share those files. The thing about that CD format that I still find to be hilarious is it’s, like, they basically gave the bullets for the people to shoot them down once a new platform came along.

SFJ: It was an amazing combination of “We are ripping you off like no one has ever ripped anyone off as a per-unit basis,” but ”We are also building a time bomb that’s going to flatten us forever.”

On day-to-day Columbia House life

SFJ: Chris is the one who got me the job, by the way. I was lucky enough to have him befriend me and basically underwrite my band by giving me this job. None of us had very much to do. We would basically work for a few hours, and then just fucking joke around.

AA: [Laughs.] We just hung out in each other’s offices.

SFJ: [A co-worker] and I would just sit there cracking up for hours, and then we would go to the cafeteria and come back and crack up some more and go to some weird meeting, and somehow it would produce this catalog.

CW: There was this way in which it was remarkable how much manpower there was to make something so small. That those music catalogs required 30, 40, and 50 people to proofread them and write the content. You think now how few resources you use to do something equivalent. It is sort of breathtaking there was so much time on our hands.

AA: There was so much money floating around.

On producing the catalog

SFJ: There was a part of [Chris’] assignment which was somehow to make the catalog seem like a magazine, as if we were really going to fool people into thinking, “Oh, what a hip magazine about alternative music! And I also have the option to buy things!” As if it wasn’t obviously a catalog. That was one of the most hilarious things: We were trying to almost read like Raygun or Spin, but nobody was fooled. They came in the Columbia House envelope; they knew what it was.

CW: That’s true, but one of the things we were doing… It was that curating model. They would send you this thing that almost looked like a tax document. It had lists and numbers, and we would invent features and curate things and collect things and organize things thematically. That was an innovation in that world, that we imposed a sense of taste…

PO: It’s consumption as curation. In that way, it too was mirroring what has become a standardization on the internet. What you have is ways to buy shit that tries to pretend that it’s not just ways to buy shit.

AA: We had a lot of fun doing it. We had a lot of creative, overeducated, overqualified people who were just dicking around having the best time with each other, and coming up with these crazy headlines and spreads. I got into writing factoids. We’d have theme issues. This is before we had the internet, so I would go to the local library and look up factoids. [Laughs.] Which is just crazy to me that I would spend afternoons at the branch library in midtown Manhattan coming up with the origins of Valentine’s Day to put in the music catalog. So much of that attitude made its way into the catalog. None of us thought we were producing high art, but we were having a lot of fun doing it. Looking back, it’s amazing we got away with that for so long.

SFJ: I always say it’s the best day job I ever had, because it was, for some reason, incredibly low-pressure and high-fun. A lot of that stuff felt, in a not-negative way, [like] gaming the system. We would end up having a conversation along the lines of, “I don’t know, I really like the new Cell record.” And nobody was buying the Cell record, but they were Sonic Youth’s roadies, so I really liked it. We would put it up front with a goofy graphic, and maybe that helped move two, three thousand copies. Sometimes we would really push the stuff we cared about. And who knows how it affected consumer behavior? But there was an aspect to it of a completely goofball endeavor that we weren’t taking 100 percent seriously, but underneath it was this love of music.

CW: That was completely the goal. We found a way to organize our activities around all the people we liked. We got in a room, and we started to make this thing. We all did love music; that was an organizing principle, and the fact we could go deep into this catalog and recover things and revive things and highlight things in interesting ways. Or bands that maybe wouldn’t have gotten attention. We didn’t have any real power. It’s not like any of us were high-level executives making lots of significant decisions.

On generational clashes

AA: You were pretty young when you became a product manager, Chris. You were, like, 24.

CW: [Laughs.] It was ridiculous that I had any responsibility or power. Do you remember that at a certain point, people started to envy us? I remember there used to be, like, 20 meetings to get anything done. You’d have to talk to 10 different people. What we used to do is, we would get in a room and we would sit in there for literally six or eight hours sometimes, order lunch, and every single part of the process would get done in that room. We would pick things; we would decide things; we would organize things. And then we would also be having a good time doing it. I remember at a certain point there was some envy and resentment, like, “They’re laughing too much.”

AA: Oh yeah—I had some emails with [a former co-worker] before we met today, and she was like, “Remember when they wouldn’t let us have meetings in [another co-worker]’s office anymore, because we were having too much fun?” They actually were like, “You’re not supposed to be enjoying yourself this much,” even though we were incredibly productive. We were also given some degree of leeway because we all were young and were supposed to be kind of more “in” with the music than a lot of the executives. I felt like we were given some room to be sort of entrepreneurial. At one point, I think we were launching or proposing the website. Do you remember that, Chris?

CW: I bailed at a certain point when all that was starting to be conceived.

AA: Right. But there were these older ’80s music guys who were like, “I don’t know what you kids are doing, but you’re doing great!” But they gave us this space. In a way, the stakes were low, because it was just a catalog. We weren’t working at a music label. There was something so uncool about being at Columbia House.

CW: We were not breaking new bands; that risk was incredibly low.

On Columbia House’s business model

SFJ: The negative option—that’s what we called it, right?

CW: The whole business was premised on this concept called negative option. Which just sounds so creepy and draconian and weird, but the idea that if you don’t say no, we’re going to send you shit. It’s going to fill your mailbox, and we’re going to keep sending it unless you panic and beat us back. That was how the money was getting generated.

SFJ: Most times when you’re trying to get somebody to buy something, you are actively trying to get them to go and buy the thing, even if now it’s clicking or subscribing and subscription. Columbia House had this brilliant, perverse method which was [that] you sign up and then all you have to do is tell us not to send you things, and if you don’t remember that, we are going to sell you something and you have to pay for. And enough people will like that? Okay. And it was a profitable business. Could you ever get anyone to do that again?

PO: You can get a free trial of software, and if you don’t deal with turning it off, you’re going to get billed for $49. Again, all these things are precursors to how business is being done on the internet.

CW: You guys remember how mind-numbingly complicated the deals were? And they were always [trying to] squeeze an extra dollar out of everyone. It would be like, “2 for $3.99 gets you 4 for $4.99 and then a free CD on top of your $8.99.” You would look at these things, and nobody could rationally decode these deals. They were so gothic and complicated.

PO: My most mind-numbing moment was when I graduated up to the marketing department, and all of a sudden I had to start proofing all those deals. And all I wanted to do was just fucking help sell, like, more Yo La Tengo records. I was like, “Nooooo, I do understand what you’re getting at, but I don’t want to have to understand this needle in the haystack percentage argument.”

SFJ: When I worked there, people would say, “So, how does it work?” and I would just say, “I don’t know. I have no idea.” They were like, “Can you get me a free CD?” and I was like, “I think so.” That’s how bad I was, and still am, with anything to do with money.

On scandalous selections and “selective morality”

AA: Chris, were you there when there was that scandal around Van Halen being the selection of the month, for their album Balance? It was on the cover, and it had these Siamese twins boys. It was a huge deal.

The A.V. Club: Why?

CW: People wrote in and freaked out, right?

AA: Yeah, people were like, “This is pornography, you shouldn’t be putting this in the mail,” because there are these two naked sort of Siamese twin boys who are sitting on a seesaw. I don’t know who chose it, it was probably the rock and alternative selection of the month, and I remember it being this big deal because it was going into the Christian homes.

CW: I remember there was an understanding back then that a lot of the people receiving these catalogs were so… These were people in the middle of nowhere. That was part of the idea of it: You had to order music through the mail, because you had no access even to a record store. Therefore the audience was often perceived as infinitely more conservative than maybe they were. But I also remember there was this selective morality. They wouldn’t put a record on the cover, but all of a sudden Snoop Dogg’s record would come out, and they knew that thing would be huge as a selection of the month. They were very selectively moral. [Laughs.] Their morality was kind of random. That Van Halen one—they got a lot of letters about that one, right?

AA: Yeah, they did. That’s what I forgot. You couldn’t buy music online, so people really relied on Columbia House if they lived out in nowhere.

On indie rockers as Columbia House fans, and personal recollections

PO: I totally remember having conversations when I started bringing indie labels to sell their wares at Columbia House. The one that I remember specifically was [Stephen] Malkmus, right around the last Pavement record, being like, “Yeah, I got my Creedence records through Columbia House, so why should I give a shit that I’m getting paid less? I like being in this thing.” [Yo La Tengo’s] Georgia [Hubley] and Ira [Kaplan] got into Columbia House when the Matador [Records] deal went through Atlantic, and I was basically lobbying Matador to sell their stuff there. Georgia and Ira were like, “Yo, think about this: We’re going to be in front of people who don’t know where you can buy a Liz Phair or a Jon Spencer Blues Explosion or a Yo La Tengo record. Why not do it through them?”

SFJ: Scattered through many musician interviews and oral histories, you hear a lot of stories of people early on who really did have no other way of getting music, and how important it was to them. And, even as a kid in Fort Greene [in Brooklyn], I subscribed to Columbia House because I wasn’t allowed to go buy things on my own yet. I would wait and wait for my ELO record. One of the most disappointing moments of my life was [when] I came back from vacation knowing that Kiss’ Alive II was going to be in my mailbox, and for some reason the son-of-a-bitch mailman, as if he didn’t know what he was doing, folded the fucking thing in half and put it through the slot.

All: [Rousing chorus of everyone groaning and saying, “Nooooooo!”]

SFJ: Or that might’ve been Aerosmith’s Rocks. You’d wait and wait and wait, and if you were too young or too anything, it was, in some ways, the only way to buy records.

PO: When I came to the States, Columbia House and whatever at the time it was called—it wasn’t called BMG Direct at that point—but whatever the other one was, that’s how I got my first records when I was trying to understand the difference between Led Zeppelin and Rush. I fully, as a young immigrant, got all my first rock records through them.

CW: There’s also a passage in one of the Kurt Cobain biographies about how he too got his first Black Sabbath records through Columbia House. But I remember one disappointing thing, because I was also an early Columbia House member: Do you guys remember that sometimes the artwork, it sucked? It would only have half the artwork and no liner notes. I still have a weird copy of, like, Pete Townshend’s Empty Glass on cassette that doesn’t have the liner notes and has a weird white border around it. I think it was a way, at the time, to say, “This is different, this is generic, this has been through mail order.” [But] when they were owned by Sony and Time Warner, they owned their own CD pressing plants.

On contracts and the bottom line

CW: Piotr, you talking about interacting with bands… When I first got there, I felt very far from the music business itself.

PO: The thing that drew me there… I was in a miserable job before that. I helped build this database called Muze that turned into All Music Guide. So in some ways I’ve been fucking selling records on the internet since I got out of college. [Laughs.] I kind of was done with that, and I was doing more and more freelance writing.

One of my co-workers at Muze was hired to do A&R at Columbia House for the classical music catalog. And he said, “They’re looking for somebody who knows jazz and alternative and whatever independent label stuff is going on.” I went in there on a lark, and interviewed. In some ways, I had a lighter version of what Sasha’s describing, which is trying to write and figure out who the hell I wanted to be on one side, while going in and designing the jazz and alternative catalog right after Wilcha left. But Chris and I worked together when he came back.

At the end of an interview with The Grifters, or whoever, they would be like, “Well, what do you do besides writing for indie rock fanzines?” I’d be like, “Oh, I work at this thing called Columbia House.” The foreigners were like, “What the hell is that?” And the indie rock people were like, “Oh shit, seven CDs for a penny!” At some point, they were completely, completely interested and fascinated [by] how it worked, and [wondering] why aren’t there more indie rock [bands included]? Or, why isn’t the Drag City catalog inside Columbia House? That’s when I would be like, “That’s funny you should ask, because part of the reason I got hired was to see if I could get the Drag City catalog, and whether it’s even worth anybody’s while.”

SFJ: [Drag City’s] not even on Spotify now.

CW: Business-wise, a lot of people found the agreement sort of deplorable, right? For every one that you were ostensibly selling, Columbia House was allowed to give one away.

PO: It’s not just that. When they were selling them, the royalty rates were a percentage of what even the crappy major label royalty rates were at the time. Basically, it is so Spotify, it’s a joke. As you have mentioned, [some of the labels] were part-owners. The labels would get this enormous advance against all this product. And then, of course, that advance didn’t slide down the hill to the artists. And so they would line their pockets with it. Then they also, in exchange for the advance, allow for Columbia House to print as many copies of something as they wanted to.

AVC: There was some stat that Hootie And The Blowfish’s Cracked Rear View sold 3 million copies via record clubs.

PO: Hootie And The Blowfish! Another perfect example. Matchbox fucking 20. It’s called product, product, product, product, product. On the one hand, I absolutely agree with these guys: It was a fun job, I met the three of them, I met other people that I think are really, really smart, and had fun with it, and have stayed in touch with [people] on one level or another inside the music business or in writing, for a long time. But the deeper I got into the business aspect of it, the worse I felt about it. Fuck, I use Spotify and I know how evil on some level it is for my friends who are musicians.

But at least Spotify, that’s technology. This is personal belief: On some level, yelling about technology is like yelling about the weather. Either adapt to it, or try to create a rain machine. But with Columbia House, I could absolutely do something about it, which is not participate in it. And so when I stopped participating in the game, as a job it stopped being fun.

SFJ: All of those rates, we knew all of that stuff at the time, and it made us feel weird. Coming into the Spotify era, my label Southern has all my band’s records, [and] they just straight-up never wanted to participate. But because of the way the world works, the labels make the money first, and maybe a band sees something. My argument with them was like, “Look, I don’t care what platform it’s on. We never made a single royalty.” No Ui record ever made any money from sales. None of them. We had our 1,000 loyal fans, that’s it. And so I was like, “Put them on the internet for free, I don’t give a fuck.” The artists are the ones who are screwed, because right now the labels have equity in these streaming services. We’re getting back to all the stuff that monopoly laws were supposed to break up.

There is an alternative to that, in getting outside of it, but only if we have net neutrality. If they really fuck with net neutrality, then I don’t know what independent musicians are going to do. Right now, you can go up on Bandcamp and you can put out your record, and they take their 15 percent cut, and you can make a fair amount of money selling a couple hundred CDs. You can do okay. But if that kind of freedom is taken away, then it’s going to be a really strange game. For right now, you can post it to YouTube, you can do whatever you want, put it on SoundCloud. But once they go after that stuff, I don’t know what’s left. Carrier pigeons? What are we going to do?

On returning to Columbia House

CW: So here’s what happened to me. I was there super-early, like ’93 to basically ’95. And then I left. I went off to graduate film school and made The Target Shoots First. When I came back to New York, I was like, “How am I going to make a living?” I just went to film school, blew all this money. I came back to New York, and I was staggered how I was not welcome anymore on the island of Manhattan. I sound like grandpa here, but you could live a semi-bohemian life and still be on the island itself. When I came back in 2000, I was like, “Holy fuck, I am not welcome here anymore.” You needed five, six, eight grand just to get an apartment’s first month’s, last month’s rent.

AA: That was right before the crash of 2001.

CW: I got a job at a dot-com called Insound. This was during the harrowingly delusional dot-com era, when these guys, who were really great guys, were convinced their record-selling website in a loft in SoHo was going to be valued at $100 million. I worked there for a grand total of like two weeks when their money fell through, and all of us were let go.

I found myself jobless and semi-terrified. Just because I had gone to graduate school and made a first-person documentary meant absolutely zero in terms of my ability to generate any income and actually live in New York. So there was this brief moment, I don’t even know if it ended up being a full year, when one of my old employers at Columbia House called me and said, “Hey, we’ve got a position. Would you be interested in this?” And it was with incredible, tortured ambivalence I went back. But I went back with this idea that I am going to use this time to work here, but I’m also going to try to get this film out in the world. The crushing, weird irony of that second time going back to Columbia House, is I would spend my entire time sending out VHS copies of The Target Shoots First to film festivals, and writing letters to film critics in Portland and Chicago and trying to get them to write about [the movie].

PO: And then is when I met Chris. I got there [originally] right after he left.

AA: I was always in the creative department; I left very soon after getting promoted to the marketing department, because it was sort of a wasteland and felt kind of lonely. I left to go to someplace in Silicon Alley. I had been an intern at Columbia Records in college, and I moved back to San Francisco, moved back to New York in ’94. I started temping at Columbia Records and temping at Columbia House. The first job that opened up was at Columbia House, and I met Chris then. I distinctly remember having conversations with Chris, because there was all this drama going on with turnover of people.

I was only at Columbia House for three years, but it looms much larger in my mind, probably because it was my first real New York job. Moving up from working in creative as a product coordinator first… going on these wild missions. Chris would get these ideas for layouts: It would be a layout of hippie music with the headline “Taking Birken-stock!” Instead of “Taking Stock” or something. I would have to go get Birkenstocks and scan them. Do you remember that?

CW: Oh, classic.

AA: I’d also deal with the labels and have to get art from their publicity departments because you couldn’t get art online. I’d have to get the publicity stills or any weird photos. Sometimes we’d have to find CDs at the last minute that we didn’t have access to, that I had to scan the cover of. I would go all over Midtown to these record stores. I was on the ground doing that, then moved up into editorial.

I would hang out in Sasha’s office. He was turning me onto Cat Power and so much great music. I was so young at that time, and there was music piling out of everyone’s office, and people playing music. In my office, we’d have the TV going all day long, so we could be up on who [was] on the charts, because that was our job. I shared an office with this woman Sharon Russell. In the afternoons, we’d watch My So-Called Life and then her talk shows and stuff. It was like, “I can’t believe we’re getting paid for this!” It was so shocking.

I moved up to be a product manager. Marie [Capozzi, featured in The Target Shoots First] had jumped over to BMG, because BMG was a big competitor, and they were poaching people. [At one point I recalled the person who hired me was] just sitting in this big, huge office with really expensive stereo equipment, like, a wall of CDs. It just felt dead to me. Like, there was nothing creatively happening, it felt like. I had this idea that there’s all these internet startups that were starting to get attention, and I left to go to this place called iTraffic and to do advertising for CDNow. Before Amazon was selling music, CDNow and Music Boulevard were where you could get CDs online. I worked there for a total of six months. [Then] I did a total about-face and ended up at the New York Public Library doing events and development writing. I’d always loved music, but when I was at the library I started an MFA in the evenings, worked on the book that I eventually published a couple years ago [Fairyland], which is my life now.

On balancing work and side projects

AA: Sasha, when you were working—you had Ui going on, you were writing music reviews for the New York Post, you had all these side projects you were able to do at the same time.

SFJ: One of the millions of reasons that I’m probably almost on the verge of leaving New York and being yet another person in L.A. is the intensity here to just make rent. Especially looking at my younger friends in their late 20s, I feel bad for them, because they’re grinding. They’re working their asses off. They’re working so much harder than we did, and they’re barely having time for their own projects. One thing about the fat, Clintonian, CD money years, is that in New York, you could still skim off some of the industry money and be an artist. Now, the financial demands of the city are so absurd that it is squeezing people left and right, even people who make reasonable money.

AA: When I was working at Columbia House, I was sharing an apartment on Seventh Avenue South off of Bedford Street, so the West Village. I was sharing a small two-bedroom for $1,200 a month.

CW: Everyone, especially in that creative department had other things going on. [Some people would] be writing for music magazines, when you could still make a little money writing record reviews and criticism. Piotr, you did that, right?

PO: Totally.

On business now versus business then

PO: I’d known of Columbia House since my second year in the United States. It was a big company; it was a company that would not go away. When I took a job there—and Muze was at the time a startup, and it was growing—but I was like, “Columbia House, that’s a real company. I’m going to work for a real company.” That was my first realization that absolutely everybody is making it up as they go along. They have no fucking idea. The more they say to you, “This is how it’s going to happen, this is how the world works,” the more they are actually faking it.

I absolutely felt that way at Columbia House. The only people I trusted there were the people who were kind of like, “Okay, I’m going to go write over here,” or “I’m going to go make some music,” or “I’m going to go make a movie,” or “Hey, I just started DJing down at Ludlow Street,” or “Hey, do you want to go to a party in Bushwick?” which at the time was kind of a big fucking weird deal. The whole notion of making it up as you go along came from there. The people that I thought knew what the hell was going on and how the world worked, obviously did not.

SFJ: This is more about the economy in the ’90s and labor and all of that, but one thing that’s sort of crushing about this moment for everybody who used to have a reasonable quality of life, is now… Let’s say we were all engaged in any of the stuff we were talking about: outside writing, film, or writing a book. I don’t know what the analog to Columbia House would be now, but on top of it all, you’d be asked to hand in a blog post, and you’d be obliged to tweet about it, and you’d be obliged to do some other thing. And your work day would just be filled with all of this pointless content creation, and the pressure. The fun would be crushed out of it. You wouldn’t go home thinking, “Oh, ho ho, that was a goofy fun day,” because there is a point at which the human being gets stretched beyond its natural limits. A lot of people right now are wondering, “What the hell did I get myself into? I can’t do this much work.”

This is all so much more work than anyone dreamed of doing five or 10 years ago. Because there’s this mad scramble to be like, “What do people want to read? What do people want to subscribe to? What do they want to click on? So let’s make all of it. Let’s do all of it. Let’s make every version of everything. Let’s make an app.” We didn’t have any of that kind of pressure. This is all about what human labor is worth, and how far people are asking other people to go. Right now, I see everyone around me, including me, being asked to do seven times the amount of work we were being asked to do, and they don’t know what to do.

AA: It’s true. People are getting burned out. People work too much now. They constantly have to be reading online at their desk and doing updates on their desk. We would take lunch breaks.

SFJ: And the cafeteria was pretty good. [Laughter.]

AA: The Time-Warner cafeteria was the really good one. We could sneak into that one.

The AVC: Why did you have to sneak into that? Didn’t Time-Warner own the company?

SFJ: Chris was able to get me in, because he was an executive.

CW: Oh, please. Blogga, please. [Laughs.] For some reason, the marketing department held more sway there.

AA: Oh my God, there was so much stratification between the two floors [marketing and creative].

SFJ: I had absolutely no power. I was just a writer.

AA: The creative department was definitely the lowest of the low. The dress code on the different floors was really drastically different. On the business floor, the marketing floor, you had to look pretty put together. Even if you were a product manager, you had to look pretty good. Even though you had Karl Groom in his socks going down the hall.

On stupid but iconic questions

CW: By the way, this is a stupid, iconic Columbia House question that I don’t think I ever got a satisfactory answer to: Every person who would find out that I worked there—every relative, every friend—would be like, “Oh, I signed up as Hugh G. Erection” or “Patty O Furniture,” and they never caught me. I feel like I remember asking, and someone saying, “There’s a percentage of that built in, there’s a percentage of fraud that happens, and it’s not significant enough to matter to the bottom line.” Did you guys ever remember asking that question?

PO: Isn’t there a loss leader in every business?

CW: I just remember that was such a feature of “I scammed Columbia House”: “I was Abe Lincoln” or whatever.

AA: We’ve just been talking about how Columbia House scammed so many people, how they were scamming artists and how they had such a huge mark-up. They could totally afford to be scammed many times by Hugh G. Erection.

All: [Laughter.]

AA: The launch of the alternative catalog that Chris, you oversaw, was this big deal. We were actively always reading these letters from people, responding to see if they really liked the catalog. I remember one kid saying, “Whatever you guys choose as your erection of the month!” [Laughs.] I thought was so great, because it was the selection of the month—but it was the erection of the month!

SFJ: Chris, I remember we caught up again after you had come back from Cal Arts with the movie. This may be a complete reconstruction that is not true, [but] I have this memory of at one point Playboy.com was the most popular website in the world, and for some reason I have this idea in my head that the Columbia House website was huge for a moment.

CW: I remember that too. It was one of those functional things. Piotr, maybe you can speak to this. Because they had such a high membership, and it became this way that you could use this tool that had such vast reach. It was almost like the library going online. The population of people using it spiked so profoundly.

PO: I almost know why. This is after I left to pursue writing full-time. As their music business was dying, their DVD business was still going strong.

AA: Oh yeah, and TV shows, too! There would be TV Shows on DVD.

PO: Basically, for a minute, they [pioneered the] idea in some ways of Netflix—not with streaming, but with subscription to getting movies. Probably with the same markups that the music club had. For some reason, I have the memory of the DVD club doing very, very well, dovetailing with the time when the website was a huge website.

CW: That makes sense, because that was that exact same moment, like when I first got to Columbia House, where had basically they had convinced everyone to re-buy their record collection again at double the price. So to then, all of a sudden movies became, “Hey higher fidelity, get rid of your VHS [tapes]. You have to own everything on DVD.” It was the fumes of being able to re-sell stuff in a digital transition, all over again.

On small victories

SFJ: One thing about the culture there that bears mentioning, is that it somehow was not in any way a noxious or a bitter culture.

AA: It was very open because the stakes were low. A label would be more cutthroat, people would try to keep each other down. That wasn’t the culture at Columbia House.

CW: Piotr brings up Yo La Tengo; Sasha, you talked about Cell. I even remember Teenage Fanclub. You’d say, “I like this record, I’m going to pluck it from the listings and highlight it, and maybe that band will see a hundred, a thousand, three thousand more sales because of this decision.” Even though the label agreements were so onerous and the band were getting fucked in all these ways, you did feel the tiny little corner of influence you had. That every once in a while you were trying at least to do something to [help] the people you were the most behind, the bands and the artists.

SFJ: Erika [Anderson], who’s now EMA, she lives in Portland. She grew up in South Dakota, and there are places where you could not just drive to a bookstore. You could not drive to any record store. It wasn’t even an option. The ability to get the Liz Phair record from Columbia House wasn’t minor; that was a big deal. And it meant a huge amount to somebody, even if, say, four years later the internet changed everything. A lot of people, their first record they bought with their own money was something like [Liz Phair’s] Exile In Guyville or [Sonic Youth’s] Daydream Nation or [A Tribe Called Quest’s] Low End Theory.

The AVC: How did working at Columbia House inform how your lives are now? Is there anything specific you can pinpoint?

CW: I think one thing that was a generational obsession at that time, which I’ve been thinking a lot about, is we were always interrogating this idea of selling out, and thinking about what selling out meant, and how we were contributing to us selling out, or selling out our generation. One of the things I’ve been reflecting on a lot lately is, What did that mean? How did that evaporate? A band coming out [now], getting your music heard and cutting through the noise of everything and being in a commercial is completely acceptable. I still sort of hold dear to some of that stuff.

But the irony is, something from that era I had to reconcile was trying to figure out a way to make a living where you could do completely pure, creative things and then figure out another way to generate income. For me, that balance has been directing commercials and doing documentary projects as a sidebar, because those just don’t pay anything. I feel like some of that formed in that Columbia House era, where we all had that job, but were trying to figure out our identities and how to do other things that weren’t going to compensate us in a way that we could continue to live in New York.

It was a formative time of trying to figure out how to do what we wanted to do, but also to make a living. That continues to be a question that’s very, very central in my life. The commercial directing jobs, and how they buy me time to do these other things.

PO: That’s a central tenet in a lot of creative lives right now. I do an exact variation of that: I do commercial work for brands and creative agencies, while at the same time doing my little writing and my little journalism bit for people who are editors who I have created long-term relationships with. But the funny thing is that the middle ground, there’s a lot of people who can’t tell the difference between their creative work and their commercial work. I learned the difference [between those things] in places like Columbia House. I was a lot more naïve than the rest of the crew was, because I thought I was going to do some good. I was going to work for a real company, and I was going to help sell more Pavement records. That was going to make the world a better place. It was there I realized that’s not how it works.

SFJ: I’m in a kind of strange moment. In some ways, it’s like returning to the ’90s, because I’ve got a couple of different freelance jobs that will hopefully bring in some money, but the bulk of the work I’m going to be doing is either this extremely overdue book or beginning a really big recording project, the first one I’ve done in 10 years. And that thing is not going to bring in any money for a while, so I’m going to have to find a way, in a brand-new city, to cover my expenses.

But there is an extremely bright dividing line between one kind of work and the other. The recording project, we were joking about it the other day, the artist and I, she’s saying, “Don’t worry, you’ll get points on the album.” That means you get $75 or something; we’re not doing it because anyone can make money anymore. It’s going to be interesting to see how that world plays out, because at least in New York, trying to fuse my creative endeavors and my commercial endeavors just became too hard to pull off. I was happiest, frankly, when I had a day job and then I went and was in my band that I never, ever had dreams of making money, ever. The day we started the band in ’90, ’91, I was like: “This is a hobby, we’re not going to make money.” The only time I made money was when I licensed my own solo guitar record, which sold maybe seven copies.

AA: It’s amazing to think 20 years ago this summer I was working at Columbia House, obsessed with this guy named Jason Schmidt, who was the Jordan Catalano to my Angela Chase, who worked in the production department, and I was writing on the side hoping someday to write this book that I eventually went to grad school for and then finally published in 2013. It was always the project I was working on. I think Columbia House was probably the most fun job I ever had, and kind of ruined me for other jobs, in a way. I was at jobs for as long or longer, but I just felt I didn’t have as much freedom as I had at Columbia House, as well as access to so much music and culture that was just fluid. We had so much free music, it just didn’t have any value. It had value to listen to, but if I didn’t want to listen to it, I could just give it away.

One thing Columbia House made me good at was copywriting, and sort of packaging copy. I [worked] over at WNYC for a while working for this show called Soundcheck, and writing a lot of copy on the website. And now I’m involved with this project called The Recollectors, helping support and promote working with StoryCorps now on it, but it’s a project to remember parents that died of AIDS. Knowing how to package and make bright, succinct copy was something I learned at Columbia House.

After that experience working at Columbia House, I tried working at other companies. I didn’t want to be in a sort of corporate, unhappy job situation. I have a lot more freedom now: I am a freelance writer, I teach and I’m working on the Recollectors project, and I’m working on the film project of my book a little bit, because it’s been optioned. I’m a little bit more loose. I don’t think it informed me in this way of my creative work and my commercial work. [Later, Alysia emailed us with a few more thoughts: “One thing I should have added was that the music we were listening to then— Beastie Boys, Luscious Jackson, Beck—had this rough DIY aesthetic that we were emulating in our work at Columbia House, an organization that was cushy enough and cash-infused enough to support our wacky endeavors. I think this esprit did inform my work today, where I’m basically working for myself.” —ed.]

CW: I feel the way you’re describing your professional life is sort of the way we all do it now, which is this crazy collage of different things, and big and small, and things you care about and things that are more functional. That was a time when it was a lot more black and white, when you had a job and you had your benefits, and if you could squeeze in these other things. [What you describe] feels very… how work evolved. It speaks to what Sasha said earlier, that you’re available to tweet, to respond, to be looking at things at 10 o’clock at night and on weekends. There was such borders at Columbia House. You would leave at 6 o’clock, and you were done. We’d go out for drinks. There was so little drama there.