Four’s a crowd in Netflix’s involving deep-space survival saga Stowaway

Having already stranded Mads Mikkelsen in the Arctic Circle, director Joe Penna apparently decided that his next survival film would amp up the desolation, settling upon the only plausible option: outer space. This time, however, the struggle for resources involves a horrific moral calculus, to be worked out by a crew of four. As the title suggests, it was meant to be three; Stowaway opens with the launch of a rocket headed for Mars (the year is never stated, but there’s a colony in place), commanded by Marina Barnett (Toni Collette) and including biologist David Kim (Daniel Dae Kim) and medic Zoe Levenson (Anna Kendrick). They’re on a two-year mission, roughly half of which will be spent in transit, six months each way. Only when they’re some distance from Earth, however, do they discover that a NASA tech dude, Michael Adams (Shamier Anderson), got knocked unconscious while making a last-minute check of the ship’s innards, somehow failed to be noticed as missing, and so inadvertently came along for the ride.

Now, did they pack enough toothpaste for four people? Stowaway’s actual concern is considerably more urgent than that, and complicated by Michael turning out to be the nicest person imaginable. After an understandable initial freakout—this is the ultimate version of that old party-hard cautionary tale about passing out and awakening in another country—he declares himself ready to assist his crewmates in any way that he can, volunteering to do grunt work and eventually serving as David’s assistant for on-board experiments with microgreens. Penna and his regular co-writer/editor, Ryan Morrison, stack the deck further by giving Michael a younger sister who depends upon him (NASA, upon learning what happened, immediately assumes her care), along with a tragic backstory involving the two of them surviving an apartment fire that killed their parents. He’s pretty much the last guy in the world you’d want to politely ask to please stop breathing. But, then, none of them are “in the world” at all—and math is unforgiving.

Like everything else in Stowaway, this dilemma gets handled with a gratifying degree of verisimilitude. The launch sequence at the beginning involves enough credible-sounding jargon to make most such movie scenes feel phony by comparison; a dozen or so consultants get cited in the closing credits, and it’s clear that Penna and Morrison utilized them to fashion as realistic a depiction of manned space travel as they could, given their presumably modest budget. (One clever touch: a pendant hanging around Zoe’s neck indicates when the ship leaves Earth’s gravity and when artificial gravity kicks in.) Rather than pretend that human beings could reach Mars in one go, the film depicts how it might actually work, which involves the initial rocket docking with an ultra-long segmented craft that then rotates its way to the fourth planet, tumbling end over end. That layout figures heavily into the movie’s climax, which sees two crew members embark upon a truly dangerous 11th-hour effort to keep all four of them alive for the duration.

While ably orchestrated, this final stretch—featuring actors in spacesuits scrambling around a damaged ship—inevitably recalls Gravity, and lacks the technical facility to compete with Alfonso Cuarón at his most ingenious. Similarly, an initial solution to the problem involving David and his algae will feel familiar to anyone who saw Matt Damon struggle to expand his food supply in The Martian. That film spends half of its time on the ground observing NASA’s brain trust, but Stowaway leans into its small ensemble’s isolation. During all communications with Earth, we hear only the crew’s half of the transmission, and it’s quickly clear that nobody back home has any non-devastating answers.

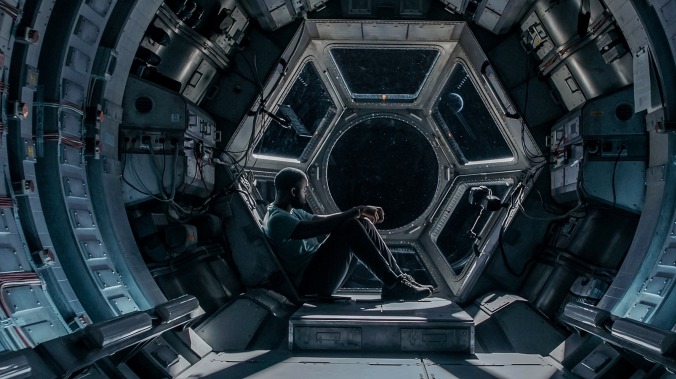

The film is strongest when simply exploring the terrible notion of triage among the healthy, with everyone involved fully aware of which individual will be deemed the most expendable. (While race is never so much as hinted at on screen, casting a Black man in that role nonetheless adds pointed subtext.) All four actors do fine work, with Anderson deftly avoiding pushing Michael’s vulnerability into the saccharine zone and the others spanning an emotional spectrum that ranges from hard-headed practicality to anguished denial. In the end, Stowaway becomes a full-fledged weepie, acknowledging the vast emptiness into which its characters have either willingly or accidentally thrust themselves. Nature doesn’t care.