Fox’s Bordertown struggles to find its place—and target

Now that there’s a real-life blowhard pushing a border wall as a “solution” for immigration, we find ourselves longing for the days when such a scheme was relegated to cartoons (namely, The Simpsons in 2009). That brand of blatant nativism isn’t going away anytime soon—certainly not before the last votes are tallied in November 2016—which means it’s currently being lampooned in the more, let’s say, liberal niches of the media and pop culture. That’s ostensibly the mission of Fox’s Bordertown, from creator Mark Hentemann, which purports to examine—and skewer—the cultural shift in the parts of the country undergoing the most notable demographic change. But Hentemann, who executive produces with Seth MacFarlane, cuts too wide a swath along the way—despite having a sizable target, Bordertown sprays its pot shots all over the place.

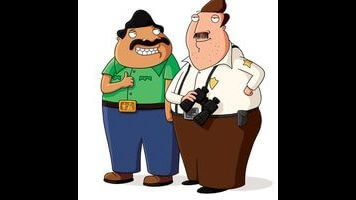

The titular bordertown is the fictional Mexifornia, which sits at the U.S.-Mexico border, a literal (if not cultural) divide. It’s home to many families, presumably, but the show focuses on the Buckwald and Gonzalez households and their patriarchs. The bigoted Bud Buckwald (Hank Azaria) is a border patrol agent whose career is going nowhere except on the occasional stroll through the desert. Frustrated by his stagnant position in life, and threatened by the seemingly unhindered progress of his neighbor, Bud mostly sits and fumes about the way things used to be, as well as all the ways the country’s going to hell. He blames immigrants in general, but directs most of his ire at one in particular—his neighbor, Ernesto Gonzalez (Nicholas Gonzalez, in one of multiple voice roles).

Bud’s an amalgam of flawed TV dads, but most of his reactionary DNA seems to have come from Archie Bunker, with plenty of Peter Griffin’s oafishness tossed into the mix. He resents the success of immigrants like Ernesto, who’s the proprietor of a landscaping business, because he thinks it’s robbed him of his own. In the second episode, Bud experiences a reversal of fortune (though that slate is soon wiped clean) that seems to encompass all of his fears. His complaint to his wife that “the Mexican has become the man, and I’ve become the Mexican,” is among his more restrained gripes, but it also echoes the sentiments of the real-life xenophobes that inform his character. But immigrants aren’t just stealing good, American jobs from good Americans—according to Bud, they’re ruining this country (though, as he notes later, this country will eventually ruin their children).

Bordertown’s counterargument rests with Ernesto, a good-natured, hard-working Mexican immigrant who lives next door to Bud with his wife and their 4-year-old son, who physically resembles Stewie Griffin, but limits himself to pranking instead of outright malevolence. It’s never explicitly stated that Ernesto’s journey to the United States was made via all the proper channels, but that can be assumed given how easily he travels across the border, even after Mexifornia passes the country’s strictest “show me your papers” law. And the landscaper doesn’t let any of the political snafus, including the aforementioned border wall, get in the way of his work, but his industriousness isn’t applauded or otherwise acknowledged by Bud.

Aside from his work ethic, Ernesto’s most prominent quality is that the dude abides—he hears Bud’s hateful comments but doesn’t take them personally, despite his father’s goading. His tolerance is seemingly propped up as the appropriate response to bigotry, because the writing certainly isn’t backing young idealists like Ernesto’s nephew J.C. (Gonzalez again), a recent college graduate who’s depicted as an effete liberal. He makes ridiculous statements like, “If I believed in fighting, I’d be making a fist right now,” while cheering on a Bill Maher stand-in who’s “standing up for the little guy while on the channel that costs $50 a month.” Hentemann and MacFarlane continue to trade in extremes here, and so J.C.’s bleeding heart is mocked right along with Bud’s hate speech.

It’s not clear why the show’s producers and writers settled on that particular binary, which deems J.C.’s leftist views almost as reprehensible as Bud’s Tea Party dogma. Although Bud is a protagonist in the series, destined to eventually surrender to progress, he’s also very much a part of the old guard. He represents the anti-immigrant stance that the show doesn’t so much criticize—at least, not in the two episodes made available for review—as shrug off as oblivious and creeping toward obsolescence. People like Bud (read: bigots) are dying out, Bordertown wants you to believe, so let’s laugh at their ignorant ways on their way out.

And if that were the only position that the show took, the humor would be more focused, but it also wouldn’t be a Hentemann-MacFarlane product. The pair has spent years making it clear that no topic is taboo, no entity too vaunted or pitiable to remain off limits. Which is why Bordertown is open for “equal opportunity offense,” sending up everyone from poor whites (who are mostly depicted as inbred and slovenly) to famous actors (there’s a Philip Seymour Hoffman joke thrown in for not-so-good measure). There are also plenty of cutaways and a running alien probe gag that’s just one long, awful rape joke. After setting up a target like Bud, the show just diffuses its satire by making digs at progressives and the less fortunate.

Because Bordertown takes the time to mock everyone, it takes the sting out of the more pointed irreverence, such as when a border patrol agent describes former President George W. Bush’s career trajectory after bottoming out. The show’s writers include prominent Mexican-American political cartoonist Lalo Alcaraz, who also serves as a consulting producer, so there’s hope that the show will eventually find a voice that’s not a mere echo of Family Guy.