Fragments Of An Infinite Memory traces the decline of the internet through one man’s eyes

What did the internet used to be like? I’m not sure I remember. The conventional wisdom is that, even six or seven years ago, it was more fun and less serious. The dismissive claim that “the internet is not real life” seemed more true than not. Social media platforms were black holes for people’s free time, and that was the major knock. This all seems inconceivably naïve now that things have so severely deteriorated, now that the rapidity with which misinformation and society-altering conspiracy theories spread is so clear, and people spend more time logged on than ever.

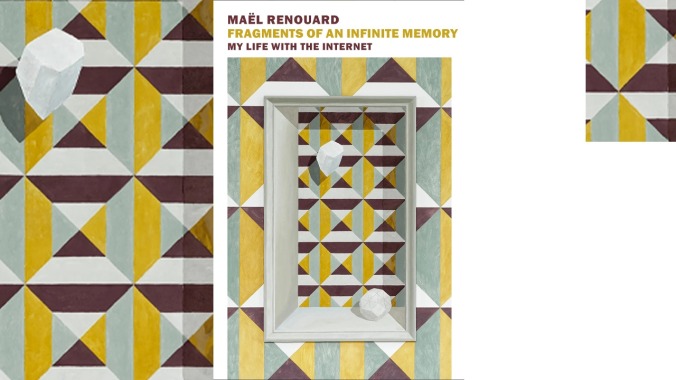

Fragments Of An Infinite Memory: My Life With The Internet by Maël Renouard—a French writer who, among other things, served as a speechwriter for François Fillon when he was prime minister—was published in France in March 2016, as the online experience was rapidly worsening via algorithmic timelines, unmoderated harassment, and growing alienation. The book is, as the title suggests, written in a series of discursive segments exploring the ins and outs of Renouard’s time on the internet. Now, nearly five years later, it has been translated by Peter Behrman de Sinéty into a very different world, which logs on to a very different internet. The delay in publication situates the book oddly. Not new enough, with the speed at which the internet changes, to feel quite like it represents now and not old enough to seem prescient, as with 1981’s Within The Context Of No Context by George W.S. Trow or 1985’s Amusing Ourselves To Death by Neil Postman.

The difficulty in reading this book as a work that is neither new nor old appears early on, when Renouard describes the internet this way:

[A] space in which to explore everything that crosses our minds—curiosity, worry, fantasy. Hence the ethical questions that were born along with it. Plato condemned the tyrant as someone who has the possibility of enacting his darkest passions—of actually living his dream which should have remained the only theater of those passions, in the secret recesses of sleep. Morality is what stands in opposition to the dream of exposing others absolutely to our passions.