Francis Ford Coppola apologizes for starting trend of putting “numbers on movies”

Coppola accidentally began a Hollywood sequel trend while trying to get out of doing another Godfather.

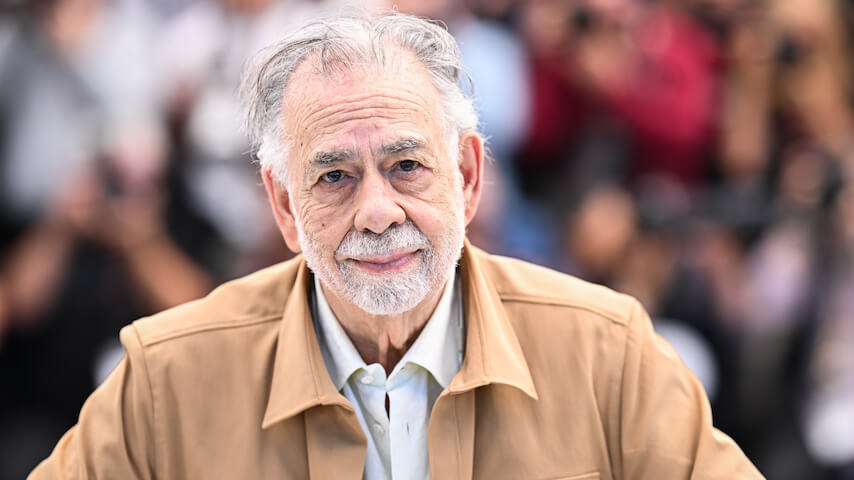

Photo by Stephane Cardinale - Corbis/Corbis via Getty Images

Sequel culture rules Hollywood today, but in the 1970s they hadn’t even begun tagging numbers on to titles yet. All that changed with the massive success of The Godfather, which made Paramount Pictures eager for a sequel. Francis Ford Coppola wasn’t particularly interested in making one, so he made a bunch of demands that he thought would be dealbreakers, like asking for $1 million dollars and to name the movie The Godfather Part II, which was inspired by the two-part Russian epic Ivan The Terrible. According to The Washington Post, the studio “thought he was nuts” and that audiences would get confused by the name, but Coppola threatened to walk, so they acquiesced. “So I’m the jerk that started numbers on movies,” Coppola now says to the outlet. “I’m embarrassed, and I apologize to everyone.”

Now, you can’t walk around a studio lot without tripping over a Part Two, although it can still be a tricky business. The latest Mission: Impossible has been rebranded with a new name after Mission: Impossible—Dead Reckoning Part One proved too much of a mouthful during Barbenheimer summer. And Wicked almost entirely hid its “Part One” designation from marketing materials, leaving some fans surprised when they got to the theater and saw the title card. Nevertheless, the trick of squeezing two parts out of one piece of source material (like how the first two Godfather movies cover Mario Puzo’s single Godfather novel) is one audiences are pretty used to by now. See: Harry Potter And The Deathly Hallows, The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn, and The Hunger Games: Mockingjay and their accompanying Part Twos.

The irony is that Coppola’s work has defined Hollywood, and now “Hollywood doesn’t want me anymore,” as he tells the Post. And the extra irony is that he says he “was almost fired on all of” his greatest films (“The lesson is that the same things that they fire you for are the same things that later they give you lifetime achievement awards for when you’re old,” he advises). Despite the decidedly mixed critical reception to his latest effort, it would seem Coppola is still an advocate for setting new trends, rather than following conventions. “Making movies without risk is like making babies without sex,” the auteur provocatively declares. “You can do it. It’s possible, but it’s not very fun.”