By 1938, Frank Capra had won two Best Director Oscars, and was one of the few behind-the-camera talents that the public knew by name. And yet his career was in trouble. His relationship with his Columbia Pictures boss Harry Cohn was strained, due to the studio’s stinginess and Capra’s sudden interest in mounting expensive, muddled prestige projects like 1937’s Lost Horizon. Just when both sides seemed bound for a protracted battle in the courts, cooler heads prevailed, and Cohn made peace with Capra by restructuring his contract and offering him the chance to direct an adaptation of one of Broadway’s biggest hit comedies: George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s overstuffed farce You Can’t Take It With You. That film—the first to feature Capra’s name above the title—became a smash, winning him his third Academy Award. He followed it up a year later with Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, capping one of the most successful decades that any Hollywood filmmaker has ever seen.

In a way though, You Can’t Take It With You marked the end of one era for Capra, and the beginning of the next. It’s not his best film. (That’d be 1946’s It’s A Wonderful Life.) It’s not even the best movie he made in the 1930s. (That’d be a tie between Mr. Smith and 1934’s It Happened One Night.) But it’s a picture that shows Capra moving beyond his screwball roots to a more expansive—and not always rosy—vision of America. You Can’t Take It With You is an upbeat, uplifting film, but with some darker shadings added to Kaufman and Hart’s play by Capra and his screenwriting partner Robert Riskin. In the decade that followed, starting with Mr. Smith, the director would be drawn more and more to the idea that the world was populated by irredeemable villains, and that simple human decency sometimes comes at a high price. But first he had to tell the story of a family of kooks and the war profiteer they befuddle.

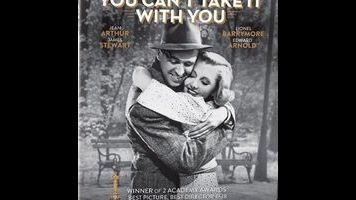

Lionel Barrymore stars in a rare non-crotchety role as “Grandpa” Martin Vanderhof, a big-hearted iconoclast who’s turned his enormous New York house into a home for like-minded eccentrics—most of which are his own children and grandchildren. Edward Arnold plays Anthony P. Kirby, a snobby, ruthless industrialist who’s buying up every property in the Vanderhof’s neighborhood to build a munitions factory. Jean Arthur and James Stewart are Alice Sycamore (Martin’s granddaughter) and Tony Kirby (Anthony’s son), whose love affair first threatens to tear their respective families apart, but then brings both clans together for a heartwarming big finish.

Capra and Riskin’s You Can’t Take It With You is at its most unwieldy the closer it sticks to the source material. The director and his cast are good at making the Vanderhof home look like something out of a children’s book, teeming with harmless wackos. But Capra has a harder time playing traffic cop with so many distractingly colorful characters, and as a result, a lot of scenes run on too long, with diffused focus. The play’s broader comic elements haven’t held up so well over the past 70-plus years; and while Barrymore gives a winning performance, and Grandpa’s “follow your bliss” philosophy remains appealing, the hero’s overall impishness is a little hard to take in large doses.

But the romance between Alice and Tony—greatly expanded from the original—is a charming precursor to It’s A Wonderful Life, with its naturalistic depiction of two bright lovebirds pecking at each other. Stewart’s adorable mumbling and Arthur’s affectionate barbs are so un-slick and un-Hollywood that they still feel fresh and engaging even now. And Capra does a moving early version of the populist set-piece he’d repeat throughout the rest of his career in a scene where the whole neighborhood comes together to pay Grandpa’s court fines when one of his family’s craft projects—manufacturing fireworks—turns out to be illegal.

The key sequence in You Can’t Take It With You, though, comes toward the end, as Anthony Kirby begins to understand Grandpa’s accusation that he’s wasted his life in the pursuit of money. The politically liberal Riskin likely had a lot to do with the harder edges of these scenes, which depict the big boss as lonely and dyspeptic. But it’s the conservative Capra who gives them their punch, doing some of his most expressive staging and framing. The shot where a defeated business rival dies of a heart attack in the extreme foreground—seen from behind, and slightly blurry—while Kirby and his lackeys are clustered together at the end of a long boardroom table, is a prime example of the despairing imagery that Capra would work with more often in the decade that followed.

The new Blu-ray edition of You Can’t Take It With You repeats the extras from an older edition: a commentary track by scholar Catherine Kellison and Frank Capra Jr., and a 20-minute featurette built around another interview with Capra’s late son. The younger Capra talks more about his dad’s sense of humor and his warm showbiz relationships than he does about his thematic preoccupations—although the featurette does mention that more creative freedom allowed the director to incorporate “ideas” into his comedies.

The real reason to watch the Blu-ray, though, is the 4K restoration, which makes each paused frame of You Can’t Take It With You look like a masterfully composed and precisely developed photograph. The vividness is especially noticeable in the climactic scenes where the Kirbys reconcile with the Vanderhofs, and everyone dances together to “Polly Wolly Doodle.” The characters are all so clear and distinct, even as the frame gets more and more crowded. This is one of Capra’s most hopeful tableaus: an eclectic group of Americans (and one visiting Russian) sharing a single space and a moment of joy. Characters would come together and support each other in later Capra films too, but more often as an act of defiance against the powerful and corrupt. Here, at the end of the director’s sunniest stretch of films, all remain welcome.