Fred Willard on playing boobs and the occasional authority figure

Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

This piece originally ran in July 2012. The A.V. Club presents it updated and in its entirety in honor of Fred Willard, who died Friday at the age of 86.

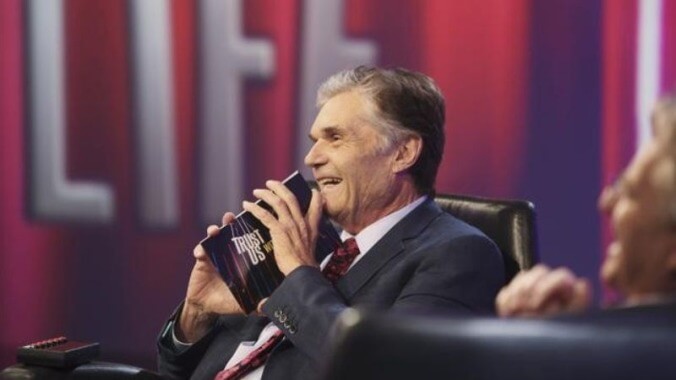

The actor: For more than five decades, Fred Willard has channeled his affable comedic presence into numerous boobs and buffoons, in addition to the occasional authority figure. (He ran a country on Lois & Clark: The New Adventures Of Superman and advocated for Method Man and Redman’s Harvard matriculation in the 2001 stoner comedy How High.) The alumnus of Chicago’s famed Second City is a key player in Christopher Guest’s stable of comedic performers, a collaboration that stretches back to his cameo as a military officer in This Is Spinal Tap. Willard can currently be seen as the host of ABC’s Trust Us With Your Life, where his interviews with celebrity guests like Ricky Gervais, David Hasselhoff, and Jack and Kelly Osbourne inform the improvisations of Wayne Brady, Colin Mochrie, Greg Proops, and others.

Trust Us With Your Life (2012)—Host

The A.V. Club: How much prep work went into the interviews that form the basis for the show’s scenes and games?

Fred Willard: The producers would interview the celebrities, and they would pick out parts of their interview that they thought would lend themselves to the improv. Then they’d come in and talk to me about it, and I would do a run-through with an assistant, who’d sit in for the celebrity. The improv actors were another group—not the guys you see on TV, a different group that would come on. The real improvisers—Wayne Brady and Jonathan Mangum and others—didn’t want to hear the stories; they didn’t want to know anything. Which just amazed me, because I’ve done some improv, and to me, the more information you have—I like to kind of mull it over in my mind.

I think they coaxed the celebrities to stay pretty much on the script, and if they got off the script, I would lead them back in, which was tough, because sometimes they have such interesting stories, and it was my job to say, “That sounds very interesting, now tell us about your senior year in college, an incident that happened…” And they would get back into it.

AVC: Did you get a chance to mix it up with the improvisers?

FW: Ah no, luckily. I had no desire to, because they were doing stuff that just amazed me. The celebrities did occasionally; they would get the interviewee up, and he’d have to either play himself or another character, but he didn’t have to say anything. They made it easy for him, they’d have one of those improv games where one of the actors would speak for him.

AVC: You have a history of playing hosts in fictional and nonfictional capacities. What is it about Fred Willard that says “host”?

FW: [Laughs.] The strange thing is, if I go to a party, I’m very quiet. I guess a lot of actors are that way: You just sit and take in characters. But that’s overcome by my basic interest in what makes people tick. I love to talk to people about when they got started, how they first knew they were funny, when was their first this and that. That overwhelms my reticence, my shyness. I don’t mean to say I make a great host, but that makes it easier for me to host. Another thing I hate to do is man-on-the street interviews, those I dislike. Or talking to an audience when you have time to kill: “All right, get up and fill.” I think the hardest job in show business is the audience warm-up guy at a sitcom. These guys have to keep the ball in the air for, sometimes, hours a night, and just play games with the audience, and do “hey where you from” and “is that your girlfriend” kinda stuff. I want to be a million miles away from that.

Tim And Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! (2007-2009)—“Tragg”/“Mancierge”

AVC: You’ve had a chance to work with a younger generation of comics in recent years. Do you feel a kinship to the Adam McKays, Judd Apatows, and Tim And Erics of the world?

FW: The Tim And Eric experience was very strange. I was not familiar with their show. The first one I did, I just did. It was done in pieces, and for about a year afterwards, I’d be somewhere and some 18-, 19-year-old would come up to me and say, “Oh you were on the Tim and Eric show, you were wonderful.” So I called my agent and said, “Listen, if Tim and Eric ever ask me to be on the show again, say ‘Yes’ immediately, because they’re doing something that appeals to young people.” So they called me back in to do another one, but I still had no idea what I was doing. I seemed to be reading from a phonebook and ordering Chinese food. I don’t think I ever met Tim and Eric. I think they were on the set, but it was just very strange. I’d be there for an hour, and they pieced it together.

Anchorman: The Legend Of Ron Burgundy

(2004)—“Ed Harken”

Wake Up, Ron Burgundy: The Lost Movie (2004)—“Ed Harken”

FW: As far as Adam McKay and Judd Apatow, good comedy never ages. It’s not like, “Wow, what people are doing now!”—except people can get away with more on TV and movies than they did 30, 40 years ago. That’s the only change, but it’s still funny. You gotta have something funny, something that appeals to the audience.

AVC: Will you be coming back for the Anchorman sequel?

FW: I haven’t heard. I doubt that I will because if they’re going to write a script, I think what they do is call and say, “Do you want to be part of this?” I don’t know, everybody is asking me that—I had a great time doing it, I love working with Will Ferrell, but who knows?

[Anchorman] was one of the few times I ever broke up on camera—the scene where he’s just, “Go fuck yourself, San Diego,” and then he’s completely oblivious to what he said. The way he reacts to it—“good show guys, good show”—and I was the one who has to come up to him, and, as he leaves, I’ve gotta follow. I started to laugh, but he suddenly stopped and said, “Okay, let’s do that again.” Honest to God, I was laughing so hard—by the fourth take, when the scene got to me, I could do it without breaking up, because you just hate to break up a take by laughing. But that’s one of the few times—one of the other times was on Waiting For Guffman. People always ask me, “How do you do it without breaking up?” But it’s like laughing in church: You can’t do it, you shouldn’t do it, but that makes it all the funnier. And I found the best thing—I’ve tried to think of sad things, but it just keeps coming back—the best thing is to stop the cameras, and just let me laugh for five minutes and get it out of my system. Then I say to myself, “Do you want to be here at 1 in the morning doing this scene, or do you want to do it and be home by 9 o’clock?” So that’s how you sober up.

Waiting For Guffman (1996)—“Ron Albertson”

Best In Show

(2000)—“Buck Laughlin”

A Mighty Wind (2003)—“Mike LaFontaine”

For Your Consideration

(2006)—“Chuck”

FW: Christopher Guest, he’ll call and say, “We’re doing this movie, and I’d like you to play—” and he gives you the character, then I always like to enlarge on the character. Best In Show, he wanted me to be the Joe Garagiola part—he was the color man. So I said, “That’s what I’ll do, I’ll be an ex-athlete, who thinks that the whole world is watching a dog show, but would be fascinated by his own personal, physical triumphs.” So that’s how I played it, and I got into Joe Garagiola’s speech patterns, the way he would—[Affects staccato sports-broadcaster voice.] sports… announcers… have… a… rhythm… like… that [Ends affectation.]—and I copied a couple of the ways he would tell jokes. The movie before that had been Waiting For Guffman, and Christopher had filmed so many hours of material and so much of it got cut. I [thought], “I’m the color commentator, I’m gonna be off-camera or end up on the cutting-room floor, so I’m gonna say everything that comes to my mind. I’m not going to hold back if I have a thought, I’m gonna do it.” Surprisingly he left a lot of it in, which was great. So it’s a triumph to me when you go see something you’ve done, and most of your stuff is left in. Doesn’t matter if the movie was good if you were good. At least they left my stuff in, because a lot of times, things are left out, and you say, “Oh damn, that was my best line, that was the best moment.” I remember I once talked to Harvey Korman, and he said, “I’ve done movies just because of a certain scene, and they ended up cutting that scene out of the movie.” So I think the key from that is you’ve got to produce your own films.

The one from A Mighty Wind, I also enlarged on that character. Christopher said I managed this group, and I thought it might be funny if I had been on a television series—maybe one season 20 years ago—and thought everyone remembered the catchphrases and all. That’s always a funny thing, when people think they’re known for every little thing they ever did, and they’re really not. So I had a lot of fun with that.

AVC: Was an additional part of “enlarging” that character the hairdo that you wore for the role?

FW: Ah, yes. That was my wife’s idea: She saw an old rock group like Journey or Foreigner, and she loved the fact that one guy had his hair dyed blonde—but he still had black roots. So I was going to ask Chris about it, but I knew from working with him that it’s not a good idea to run an idea by him first. So I just went out and did it, and when I went in to shoot it, he did a take—like in the old cartoons when they jump back—and he said, “Oh, I don’t know.” The hair lady was there, and she said, “We can dial that back, dial that down.” I’d seen these suits—I was in Cleveland doing something, and I saw a store where they had these great suits, and I thought to myself, “I wish I could wear a suit like that sometime.” Then I said, “I’ll wear it as this character in A Mighty Wind,” so I bought the suits, and Chris didn’t quite like them. But the costume people said, “We can fix the suits,” and I said I would like to have a little earring in my ear, a little like a Barry Bonds cross in my ear, and Chris says, “No, no, I don’t want an earring.” Cut forward to the next movie we did, which was For Your Consideration, he said, “Fred, I think I’d like you to have a little earring.”

AVC: So after making all these films with him, it’s still hard to predict where Christopher Guest’s head will be?

FW: I’ve always said that the best way to approach Christopher is to say, “Christopher, I liked that idea you had about me wearing—” so he thinks it’s his own idea. But he can be very supportive, too. A lot of times I’ll ask him about something, and he’ll say, “Yeah, yeah—” He’s another improviser that amazes me. We were doing an improv scene for Waiting For Guffman, and I decided to tell him what I was gonna do, and he says, “Fred, I usually don’t want to know what another actor is going to do in an improvisational scene, but in your case I’d like to make an exception.”

WALL-E (2008)—“Shelby Forthright, BnL CEO”

AVC: Was that a role you auditioned for, or was that was offered to you?

FW: It was amazing; they called me, and it was like they were trying to woo me to convince me to do it. They said, “We’d like to bring you up to San Francisco and have you tour Pixar,” and I said, “Gee, my grandson is a huge fan of all the Pixar movies.” So they said, “Bring your whole family up.” They flew us up, they took me to their offices, and it was like they thought I had to be won over. I was thrilled to be up there. They took my grandson on a trip to see how they make the films, and then I went there twice to film this stuff. It was a very easy day, but they hadn’t even finished the film then, and they wouldn’t tell me anything about it. I couldn’t be told the plot, and they asked me to do no publicity for it until like a week or two before the film. So that was a very strange experience. But it was wonderful, I just loved working with them. Pixar is like a cartoon itself: The writers can design their own offices—it’s like a fun factory. And [the film] won an Academy Award. It was the only time I went to the Academy Awards, and I was sitting way back, behind the people who did Slumdog Millionaire. Every time they won—and they won every category—the guys in front of me would stand up, with their arms up cheering. I wanted to say, “We get it—you’re winning every Academy Award.” I was like in the right-field bleachers. Finally, they got to Best Animated Film, and I thought this could go any way. When they said Wall-E, I was thrilled. Because Pixar are such great people, and I thought it was such a wonderful message, that movie, for kids, without hitting them over the head about making the Earth a safe place and all. Maybe when they grow up, and they’re 30 years old, subliminally they’ll remember that message, and think twice about throwing trash or cigarette butts away.

Fernwood 2Night (1977)—“Jerry Hubbard”

America 2-Night (1978)—“Jerry Hubbard”

FW: They called me in and said, “We want you to play the Ed McMahon, the co-host.” I said, “I just got a pilot for a sitcom”—I didn’t know if it was going to go or not—“I can think of a lot of people who are better.” I started naming people, and they said, “Wait, don’t tell us. We’re interested in you. Would you just come in for a week? We could do dry runs for a week just while we work it up before we go into production.” So I met Martin Mull—I couldn’t believe how funny he was, his dry sense of humor, and the targets he would have. At the end of the week, I went to the producer, Norman Lear, and I said, “You know, I’m enjoying myself. I think I’d like to be part of this; I didn’t realize how sharp a show it was gonna be.” We really stressed that it was not a take on The Tonight Show, because, as Martin Mull put it, that would be a one-joke thing. And it wasn’t, it was just a take on the whole attitude of a small cable TV show trying to struggle by, and we tried to do it as real as possible. A lot of people thought it was a real cable-access show from this little town in Ohio.

AVC: That’s a mark of success.

FW: That’s exactly what they wanted. They would have a few guests from The Gong Show, and Martin would get very mad. He’d say, “We’re not The Gong Show, we don’t want these people, this is supposed to be real people from Fernwood who are coming on.” So he was very true to that, and we tried to use actors that weren’t recognizable from another role, so the audience would believe these are real people who just wandered onto the show.

Roseanne (1995-97)—“Scott”

AVC: You’ve worked again and again with Martin Mull, most notably on Roseanne, where you played a gay couple that was eventually married in the season-eight episode “December Bride.” While filming that episode, was there a sense that you were doing anything groundbreaking?

FW: Well, we knew we were one of the first gay marriages on television. And that episode was the wildest episode—Roseanne at that point could get anyone she wanted, she had Milton Berle and Norm Crosby, and we had Judy Garland impersonators and Liza Minnelli impersonators. It was amazing. My wife came to the show with a friend from Nashville, and at the end of the show, she said, “Now how am I going to go back to Nashville and describe what I just saw tonight?” Roseanne loved Fernwood 2 Night, she loved Martin. And she liked me, too; we never had a bad moment. I enjoyed some of her antics, and I just had a great time on the show.

Teenage Mother (1967)—“Coach”

FW: Oh boy, yeah.

AVC: Do you remember anything about that shoot?

FW: I remember a lot about that: I remember I did it mainly because it was my first movie, and I just wanted the experience. There’s a lot in movies where you memorize where you walk and where you stand. I remember I was the baseball coach at a high school, and there’s a sexy biology teacher who’s Swedish. There was a scene where I was walking down the hall, and some roughnecks had taken her into the boiler room and were going to sexually assault her. They were pulling off her clothes, and I come to the rescue—I burst into the boiler room, “Hold on, what’s going on here!” That movie came out in a very limited release. It was playing in Staten Island, and my wife and I took the ferry over to Staten Island, found the theater. And at the scene where the guys are tearing her clothes off and I burst in the boiler room, the audience booed. I was interrupting what they’d come to see. “Stay out of the boiler room! We’re having some fun in here.”

I think I was a guest on the Jay Leno show, and they hunted down that movie and made a copy of it. They showed a baby being born on camera. In those days, that was a big exploitation thing. You’d watch an actual birth; so they pushed the envelope as far as they could for the ’60s.

Get Smart (1968)—“Lundy”

AVC: You did a guest spot on Get Smart with your comedy partner at the time, Vic Greco.

FW: Yes, I did, and the pantomime scene we do, I thought of it when I saw one of these movies where a guy would have a gun on someone, and the bad guy would turn around and kick it out of his hand. I saw them once do a double kick where the other guy got it. So we carried it to an extreme. They wrote us into the show as two rookie policemen, and we did that scene. A week later Vic and I went into our agent’s office, and he said they’d offered us our own pilot to do these two characters. I said, “That’s great! When do we do it?” We didn’t—our agent turned it down. Our agent got very huffy [with the Get Smart producers], he said, “Look you paid these boys $800—which is just $400 apiece—for this job, you’re not gonna use that as a pilot.” It was not the first thing he’d turned down for us.

AVC: So how much longer were you with that agent?

FW: Well, he spared [us] the horror of having our own pilot and four-episode series, so—we had a lot of turns. It’s a tough enough business when you have people on the inside demanding that you don’t do something.

Salem’s Lot (1979)—“Larry Crockett”

FW: Tobe Hooper—he did my favorite horror movie, Texas Chain Saw Massacre. It’s still one of my favorite horror films. And when I met him for Salem’s Lot, he was the most mild-mannered guy—had a little beard, very quiet and laid-back. And I kept wondering, “How the heck did I get cast in this part?” In the first scene—I was a real-estate agent—I was supposed to leave my office and go across to this house. And Tobe says, “Now Fred, you run across the street using whatever funny little walk or run you’ve thought up.” And I go, “Oh, he wants me to be kind of a fussy little guy,” and I played it like that. The producer was talking to me once on set, and he says to me, “You know how you got this role? I saw you at St. Martin’s one Sunday.” I didn’t know what he was talking about. It was a Catholic church—my wife is Catholic—and we’d gone to church one Sunday morning. And he said, “You were sitting in the church, and light was coming through the window, it was shining on you, and I said, ‘Fred Willard, you’d be perfect for this role!’” I thought, “My God, I should have been going to churches and synagogues every weekend—maybe I would have gotten more roles.”

I later became friendly with Tobe Hooper, a very sweet man. We’d invite him over—he was coming over to a party one night, and I thought of a great idea. “When he comes, I’m going to turn on a chainsaw and meet him at the gate with a chainsaw.” But then I said, “I don’t know him that well, I better not do that.”

AVC: That’s a movie where you had to film variations on scenes, but not for comedic purposes—some scenes had to be altered because it debuted on network television.

FW: At the time, I guess it was a censorship thing. I was supposed to be in bed with the girl, and they said, “You can’t be lying on top of her for American TV, you can be lying with her. For the European version, you can be lying on top of her.” Later, when I’m being threatened with a shotgun, they said, “In the American version, he can point the gun at you—but in the European version, he’ll put the barrel in your mouth.”

D.C. Follies (1987-89)—“The Bartender”

FW: Marty Krofft told me, “Fred, you were our first and only choice,” and I was very flattered. He said—he had a very deep voice—[Affects Krofft’s gravelly voice.] “I wanna tell ya, you’re wonderful, the way you work with these puppets. Like they’re real people!” And I said, “Well that’s the only way to do it.” A month later, I was in Las Vegas, and who comes down the escalator but Louie Anderson. I said, “Hi Louie, Fred Willard,” and he said, “Oh, Fred, you’re doing a great job on D.C. Follies—you know, I turned that part down.” And I didn’t think anything of it, but later I thought, “Wait a minute, he turned it down. Who else did they offer it to before they got me?”

Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me

(1999)—“Mission Commander”

FW: I think I was just doing a countdown or something, wasn’t I? I still get checks from Austin Powers, and I feel like I’m stealing money. I was on the set for about 30 minutes! [Laughs.] People say, “Boy, you’ve been in a lot of movies,” but a lot of times they’re just little parts like that.

AVC: You were only on set for Best In Show for a few hours, correct?

FW: Well, no. The dog commentary was about four or five hours, but then the next day we came back, and I did an interview with Bob Balaban on the sidelines. Then the last night, I had to go and interview the old man whose dog had won the show. And I’ll tell ya, first they were going to do it that last night at like 8 o’clock, and then they changed it: They said it’ll be the last scene up. So I got there at 8, and by 3 in the morning, I was in my trailer, and I decided I did not want to be an actor anymore. It was 3 o’clock in the morning, they kept putting off my scene, and I’d keep thinking of jokes to do. Suddenly I say, “No, I don’t want to be an actor, I want to be at home.” We were in Vancouver. Finally they called me out to the set, and by this time I was like a bull coming out of the cage. I had so many jokes, and the scene went on and on. I don’t think it even ended up in the movie—it may be on the DVD, but the old guy couldn’t talk, and the plotline was they hadn’t told me that the guy had had a stroke and couldn’t talk. I told every medical joke in the world: There was the pretty buxom nurse and talk about anal thermometers. I told him I could bench-press him even in the wheelchair, and I asked the nurse, “How much does that wheelchair weigh?” And I was flirting with the nurse and doing lines, it was wonderful. Wrapped at about 5 in the morning, came home the next day—and, luckily, I didn’t quit show business.

AVC: How quickly did you go back on that decision?

FW: The next offer I got, the next time someone called, I said, “Oh, okay.” And now as I look back, I’ve done a lot of shows that you’re on the set until 5 in the morning—the only thing I hate is when the sun comes up, and you’re still there.