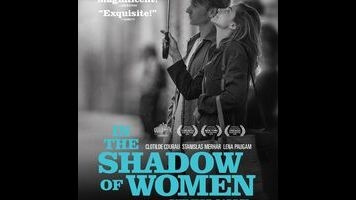

French master Philippe Garrel goes light with In The Shadow Of Women

Philippe Garrel, France’s ex-junkie film poet of doomed relationships and ghosts, has gone and made a comedy, or at least a movie that could pass for one. Invested with the ironic tenor of classic short fiction, Garrel’s unexpectedly funny In The Shadow Of Women is a cautionary tale of sexual double standards, about a self-centered documentarian who cheats on his wife and directing partner, but can’t stand the thought of her with another man. Once a fringe filmmaker who made movies about bohemians in nightshirts riding donkeys around Morocco, Garrel (Regular Lovers) bottomed out in heroin addiction and mental illness in the late 1970s, and subsequently re-emerged as a visionary of tender, haunted mini-tragedies of alienation and oblivion. There’s no denying that his early work was personal; it was too obtuse and coded to be anything else. But since making a clean break into drama, Garrel has developed a unique gift for creating movies that seem autobiographical even when they supposedly aren’t. Barely over an hour long without credits, In The Shadow Of Women is lighter than anything he’s done before, even if it does boast the most toxic protagonist since Listen Up Philip: a male chauvinist who might not be a stand-in for the director (though who really knows?), but is sketched like knowing self-caricature.

Employing droll third-person narration (read by the director’s son, actor Louis Garrel) and a sparse score, In The Shadow Of Women follows step-by-step as Pierre (Stanislas Merhar, who looks like a Slavic Mads Mikkelsen) sabotages his personal and professional life on the principle that he is entitled to both infidelity and jealousy, and his wife isn’t. Though they’re in their mid-40s, Pierre and Manon (Clotilde Courau) still live in consensual poverty like a young artist couple, their dumpy Paris apartment both a symptom and a symbol of their relationship. While working on their latest documentary, Pierre meets film archive intern Elisabeth (Lena Paugam) and begins an affair with her, only to discover that his wife has been cheating on him—which stirs up the worst of what the narrator terms “typical male equivocation.” Pierre, a pouty-faced Goofus of interpersonal relationships, is a character the movie keeps at arm’s length, poking fun at his entitlement and obliviousness. Perhaps, having made so many movies that feel like ghost stories, Garrel deserves to take it easy for once.

Still, one can’t help but miss the moody poetic intensity of his best work; though light on psychology, his films have often been emotionally claustrophobic, which has its payoff in euphoria. (Few are better at directing scenes of people dancing at parties.) Given that Garrel and his frequent writing partner Arlette Langmann—who previously wrote and edited movies for Maurice Pialat—are behind some of the best films ever made about hopeless relationships, In The Shadow Of Women inevitably comes across as a lesser work by big-time talents. (Also involved: cinematographer Renato Berta and legendary Luis Buñuel screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière; the latter shares the screenplay credit with Garrel, Langmann, and Garrel’s wife, Caroline Deruas.) And it’s true that it’s a clearer, more conventional movie than Garrel is known for making; for once, it’s actually possible to tell how much time is passing between scenes. But while this wry take on the attrition warfare of the sexes might not rank with Garrel’s best, it still has the marks of his well-developed intimate style, in which scenes are staged as though from memory, and every turn seems obscurely personal. Shot on black-and-white film that has the luster of hard coal, In The Shadow Of Women is often quite beautiful—and it has some jokes, too.