Frida

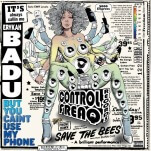

Since few lives can be squeezed neatly into a three-act structure, screen biographies are a daunting challenge, but biographies about artists are next to impossible, because any attempts to explain away an artist's inspiration are doomed to seem banal and inadequate. If anyone were qualified to tell the story of Frida Kahlo, the vibrant and iconoclastic Mexican painter, it would be director Julie Taymor, whose conceptual audacity lifted the Broadway version of Disney's The Lion King into the unlikely realm of pop art. Judging from her debut film Titus, a dark and boldly theatrical adaptation of Shakespeare's least-loved play, Taymor's taste for quixotic assignments suggested that she might find a way into Kahlo's bright, feverish artistic vision. But save for two spectacularly impressionistic sequences, Taymor brings little of that imagination to Frida, a turgid and conventional biopic that skips through the major incidents in Kahlo's life without giving them any special resonance, or even much visual panache. After numerous obstacles, including a competing Kahlo film, actress Salma Hayek finally ushered her dream project into production, but her impassioned lead performance lacks the necessary gravitas for the role, mistaking empty energy for wild fits of inspiration. Kahlo's free-spirited reputation gets a full workout in Frida's early scenes, when she bursts into young adulthood with an uninhibited mind and body, equally consumed by her devotion to art, love, Marxist politics, and wry provocation. In a cruel twist of fate, a bus crash shatters her back and pelvis, leaving her bedridden with an uncertain future while her weak-willed boyfriend (Diego Luna) slips off to another destination. But Hayek's excruciating pain and nightmare visions, realized by Taymor in a terrifying rush of skeletons and other surreal figures come to life, leads to an artistic breakthrough that commands the attention of the great Diego Rivera (Alfred Molina), a man 21 years her senior. Aware of Molina's shameless womanizing, Hayek embarks on a tumultuous open marriage that's littered with dalliances by both parties, including her trysts with Josephine Baker and the exiled Leon Trotsky (Geoffrey Rush). A trip to New York inspires the film's second eye-popping sequence—a magazine-cutout collage of the cityscape, with a nod to King Kong—before settling into an episode in which Nelson Rockefeller (Edward Norton) commissions the Marxist Molina to paint a mural inside the Rockefeller Building. As with many artist biopics, the connections between life and art in Frida are either too plain or too obscure, with few insights into Kahlo's artistic process and even fewer attempts to burrow into the troubled psychological corners that call her imagery to life. Taymor seems primed to break out into glorious abstraction at any moment, but hampered by a battery a screenwriters, questionable accents (Ashley Judd is not Mexican, Rush is not Russian), and tiresome shouting matches between Hayek and Molina, she rarely gets the chance.