NBC lost its nerve when it lost Friends

It's 2004 redux here in 2024—only now it seems all networks are NBC, keeping low-risk shows on the air, year after year

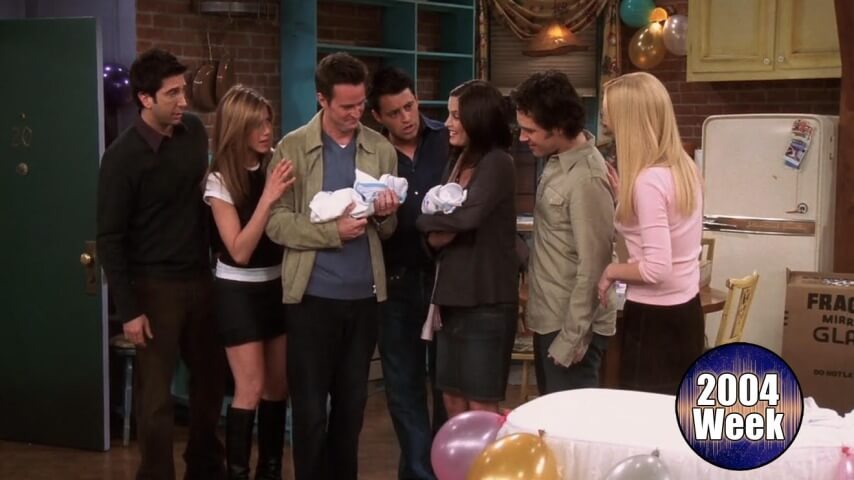

Let’s get real: There probably shouldn’t have been a tenth season of Friends. Heck, there probably shouldn’t have been a ninth, either.

This isn’t a value judgment—not entirely. Like a lot of long-running sitcoms, Friends arguably peaked around season five. It then had two or three more very good years and was pleasantly forgettable thereafter, aside from the occasional snappy episode or big event. Creatively, the show had more or less run its course by season eight. But that’s not why Friends should’ve ended then. It should’ve ended because the creators and cast had signaled, repeatedly, that they were fine with moving on. Instead, they kept the party going for a variety of reasons—but mainly because NBC kept making offers that were hard to refuse.

Before season eight debuted in 2001, there were rumors it might be the show’s last, given that the cast was already moving into movies and their contracts were expiring. But then 9/11 happened, the nation craved comfort TV, Friends’ ratings surged, and well….

Remember that 30 Rock line about how NBC’s core business strategy in the 2000s was “Make it 1997 again by science or magic?” That was more or less the network executives’ approach to Friends for its final two seasons. Keep the cash cow fed—even when it became unprofitable to do so.

In Bill Carter’s excellent early 2000s TV history Desperate Networks, he describes the state of play for NBC circa 2004. For 20 years, the network had dominated Thursday night with an unbroken string of popular, Emmy-winning sitcoms (with The Cosby Show and Cheers in the ’80s giving way to Seinfeld and Friends in the ’90s) and dramas (with L.A. Law giving way to ER). The NBC executives had built their whole schedule around that night, producing lineups that collectively outpaced their competition. Then ABC, CBS, and Fox started catching up at the start of the 21st century, with a mix of reality shows like Survivor and American Idol and exciting new dramas like Lost, Desperate Housewives, Grey’s Anatomy, and CSI. Suddenly, even Thursday nights were back in play.

NBC’s Thursday night juggernaut (so imposing that the network coined the term “Must See TV” to describe it) had been challenged before. In the early ’90s, Fox took on The Cosby Show with The Simpsons; and in the mid-’90s, CBS moved Murder, She Wrote to Thursdays to counter-program Friends. But pre-2000, NBC had always been able to pass the torch cleanly from one set of popular shows to another. That wasn’t so easy by 2004.

When Seinfeld signed off for good in 1998 (after Jerry Seinfeld rejected the kind of massive payday the Friends cast would later receive), NBC plugged that hole for a couple of seasons by moving its Tuesday night hit Frasier into the Seinfeld slot. But the network soon found it hard to develop its seemingly endless supply of “good enough to kill 30 minutes” sitcoms into modest hits—a formula they’d relied on throughout the latter half of the ‘90s. The Suddenly Susans, Just Shoot Me!s and Veronica’s Closets were replaced by the likes of The Weber Show, Inside Schwartz, Leap Of Faith, and Good Morning, Miami.

To be fair, NBC’s Thursday night lineup in the early 2000s also included, at various times, Will & Grace and Scrubs. But there was a distinct lack of zeitgeist-defining hits in the pipeline when Friends ended its eighth season in 2002. So NBC gave the show’s cast a raise (reportedly to $1,000,000 per episode) for season nine, then renewed that contract for an abbreviated season 10. Production costs rose to the point that they ate up a lot of Friends’ considerable per-episode revenue. But at least the network still had a guaranteed Top 10 show to anchor their Thursday night.

Did this decision pay off? There are three ways to break that question down.

The first is financial; and look, unless we have access to the accounting books for NBC and Warner Bros. Television, it’s impossible to say whether everyone involved with making Friends (aside from the cast and creators) made enough money off seasons nine and 10 to justify their expense. Friends has lived on in syndication and on streaming, so those episodes are still generating revenue. But an eight-season show might’ve commanded just as much in licensing fees in this modern era, where number of seasons and number of episodes don’t seem to matter that much to outlets like Netflix and Max.

So how about the creative side? Again, it’s hard to keep any TV show fresh for more than five or six seasons. Sitcoms are especially prone to ossification. Over time, characters stiffen into stereotypes and jokes get repeated so often that they become dryly liturgical—like the part of the church service where parishioners mindlessly mumble the creeds in unison. But also like a church service, watching the same sitcom week after week can be stabilizing, reassuring. This is why hit sitcoms run so long. Dramas have to keep coming up with stories and stakes. With a well-liked sitcom, all fans really want is to hang out with their friends (or their Friends) for 22 minutes.

Or to put it another way: If you were to ask all the viewers who flocked back to Friends after 9/11 whether they appreciated having the show still around, they’d rightfully wonder why anyone was questioning it. (One might also ask whether these fans reflexively stop on a season nine or 10 Friends rerun when they’re channel-surfing past TBS as often as they stop on one from season four or five. But that’s another matter.)

Perhaps the most revealing way to think about the latter years of Friends is culturally. Did NBC’s stubborn refusal to let Friends go cost it some momentum, right as American TV viewers’ tastes were changing? Shouldn’t the network have been developing its own answers to Survivor and Lost? (Heroes, in case you’re wondering, didn’t debut until 2006. And The Apprentice… well, we’ll get to The Apprentice.)

It’s worth noting that two other popular sitcoms ended their runs in 2004. NBC aired the final season of Frasier—though in a way Frasier felt less like a leftover ’90s show than like the last remaining link to NBC’s ’80s smash Cheers. But ABC’s The Drew Carey Show? The end of that sitcom definitely felt as much like the end of an era as the Friends finale. While NBC may have had the ’90s’ TV comedy ratings champs in Seinfeld and Friends, ABC had its own solid sitcom lineup throughout the latter half of that decade, with the likes of Spin City, Ellen, and Dharma & Greg. In a sitcom-heavy era, ABC held its own.

But ABC’s execs also had the savvy to bail early as that era started to close. Ellen wrapped in 1998. Dharma & Greg and Spin City shuttered in 2002. And while The Drew Carey Show hung on until 2004, the show had become such an afterthought for ABC by then that the final season’s episodes were burned off over the summer.

The ends of these shows—and the apparent lack of viable replacements—led to some think-pieces in 2004 about the demise of the sitcom as a major cultural force. And those essays weren’t entirely wrong, at least when it comes to the “’90s-style sitcoms” disappearing. NBC’s next big comedy hits were very different from Friends: The Office (debuting 2005), 30 Rock (2006), and Parks and Recreation (2009). ABC led its own sitcom revival with Modern Family and The Middle (both beginning in 2009). CBS connected with How I Met Your Mother (2005) and The Big Bang Theory (2007).

Only the CBS sitcom slate—including Two and a Half Men, which aired its first season the same year that Friends aired its last—consisted of “traditional” sitcoms, shot with three cameras in front of an audible studio audience, like a playlet. The other network’s hits were single-cams, often shot with a rough-hewn documentary feel and an edgier comic sensibility, beholden to some degree to Fox’s cult favorite Arrested Development (2003). And while How I Met Your Mother and The Big Bang Theory may have been popular for much of the same reasons Friends was—their good hangout vibes—they never felt like ’90s shows that someone forgot to cancel.

In other words: Change was in the air in the early 2000s, even if NBC was slow to adjust. By 2004—during that last stretch of Friends episodes—the network felt the TV-wide shakeup enough to make a change at last to their time-tested Thursday night formula of “four sitcoms, one drama.” The hour before ER was given over to a new reality competition series… and yes, here’s where we get to The Apprentice.

Leaving aside the one big, obvious way The Apprentice changed things, that show also ended up mattering to NBC’s primetime programming practices. Freed from the sitcom/sitcom/sitcom/sitcom/drama pattern, the network could experiment more with different kinds of shows in unexpected time slots. NBC had tested those waters a bit in the Friends years with “super-sized” episodes meant to keep viewers from switching over to Survivor (back in the days when people still “switched over,” rather than just setting DVRs). But the arrival of The Apprentice signaled a more profound philosophical change.

These days, NBC’s Thursday night lineup is all Law & Order, reflecting the major networks’ increasingly reactive approach to retaining viewers. Ever since streaming services made “binging” possible, first the cable channels and now the networks have responded by programming shows in blocks. Eight Friends in a row on TBS. Three Law & Order-branded shows in a row—or three Chicago-branded shows in row—on NBC.

So it’s 2004 redux here in 2024—only now it seems all networks are NBC, keeping low-risk shows on the air, year after year. Too much of TV these days is like Friends seasons nine and 10: fine, but largely unnecessary.