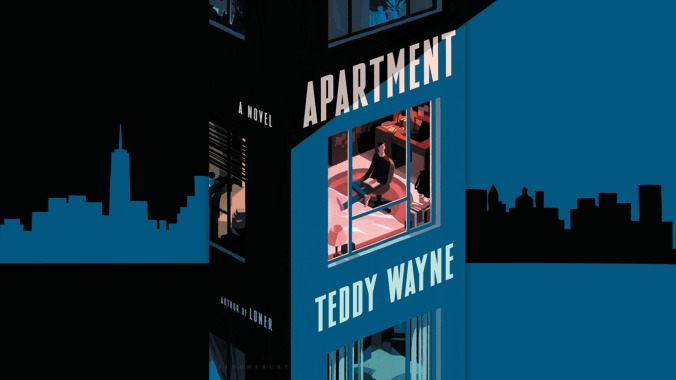

There’s perhaps no living writer better at chronicling the most crucial emotional flash points of the young modern male than Teddy Wayne. The Love Song Of Jonny Valentine, his 2013 novel about a child pop star in the mold of Justin Bieber, took an empathetic look at the erosion of an in-demand pre-teen’s trust, while his terrifying 2016 tale Loner tracked a burgeoning incel’s embrace of the dark side. Wayne’s knack for unpacking the fragility of masculinity continues to shine in his latest book, the slim, binge-worthy Apartment, especially when it’s bundled up in themes of artistic worth and privilege.

Apartment follows an unnamed, upper-class narrator attending Columbia’s MFA in creative writing program while shacking up free of charge in a rent-stabilized Stuy Town apartment belonging to his great-aunt, who’s out of his hair and living with a beau in New Jersey. He’s well-aware of his privilege and quietly ashamed by it, which is partly why he invites fellow student Billy to stay in his guest room for free. Billy initially resonates as the kind of character only a rich kid would write—a handsome, rugged Midwesterner unaware of his preternatural talent for writing about the hardships of small-town folk—but it isn’t long before this fetishization of the lower middle-class is revealed to be intentional. Our narrator sees himself as both above Billy in terms of class and status, and below him in terms of talent, and that fixation translates first into friendship before curdling into a co-dependence, one informed by school, city life, and an awkward living situation.

Apartment is foremost an exploration of male intimacy as told by a less sinister brand of loner than the one Wayne tracked in his previous novel. The narrator is not self-loathing or radioactive, but rather an unremarkable “interloper” who resides “on the borders of several crowds, never fully inhabiting them, voluntary or not.” Social interactions are a “performance,” a “canny mimicry of how I had seen others interact.” Billy, meanwhile, is the magnetic personality who brings out the best in everyone; a casual conversation for him is a revelation for the narrator. It’s easy to become possessive of a friend like that, especially once they begin flourishing outside the confines of your relationship.

Wayne uses the evolution of this friendship to explore a number of topics, from political tensions and family dynamics to artistic anxiety and the limits of privilege. What separates good artists from great ones? Are your convictions learned or ingrained? Can we become close to someone who challenges our established reality without growing to resent them? It’s a lot for a book that runs under 200 pages, and, unsurprisingly, not everything is unpacked as satisfyingly as it could be. The clash between the narrator’s casual progressivism and Billy’s center-leaning values, for example, feels glanced over, yet another rash of self-doubt for the narrator to itch. And though Wayne writes insightfully about the logic and workings of MFA programs and the existential question of what makes art meaningful, the book can’t help but feel as if it were written for other writers. That said, the narrator ruminating on the “egotistical delusion” that the artist’s “pain had more beauty, more holiness than the average person’s” will no doubt cut deep for many.

Apartment, like Wayne’s previous books, benefits from its immersive point of view. Wayne has a talent for burying us so deep in the psyches of his damaged characters that we only begin to see the true nature of their despair once it begins manifesting physically. The same goes for Apartment, which culminates in an act that would be inexplicable if we weren’t so immersed in the narrator’s justifications for it. It can feel claustrophobic, but it’s also indicative of the deep well of empathy Wayne has for his difficult, emotionally volatile characters. Longing, be it for a lover or a friend, can be as ugly as it can be beautiful, but it’s nothing if not human.