That our lives have an effect on total strangers is hardly news to ethicists, economists, or practitioners of the Golden Rule. But if goopy, everything-is-connected movies like Dan Fogelman’s Life Itself are to be believed, this simple fact of living in a world full of other people attests to nothing less than the fuzzy special-ness of being—and that its cumulative consequences have the potential to absolve our traumas and losses of their pointlessness. Admittedly, M. Night Shyamalan has been peddling this theme with panache for most of his career, and one finds roundelays of cause and unintended effect in everything from Charles Dickens to Max Ophüls to early Guy Ritchie. But Fogelman, who’s found TV success with this formula as the creator of NBC’s This Is Us, brings neither style nor substance to his second feature, a vapid exercise in narrative kitsch that spans two languages and multiple decades and love stories.

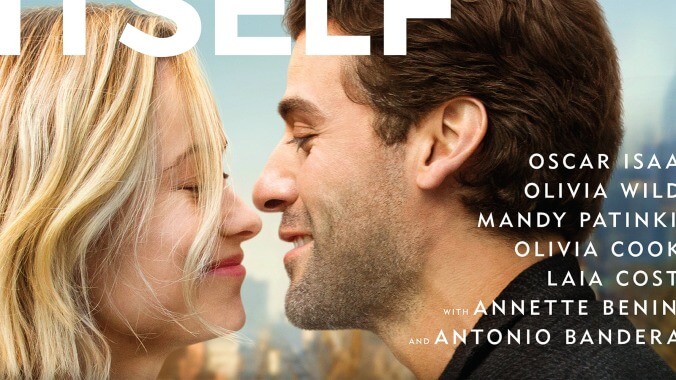

Worse still, it belongs to the dubious subgenre of pseudoliterary meta-somethings that, like The Words or The Third Person, raise serious questions about whether the filmmakers have, like, ever actually read a novel. (For whatever reason, these movies always co-star Olivia Wilde; she must have a soft spot for this crap.) It begins with a fake-out prologue narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, soon revealed to be the opening scene of an unfinished screenplay written by Will Dempsey (Oscar Isaac), a seriously bummed-out dude. Whatever diagnostic manual exists for movie clichés about hitting rock bottom, Will has all the symptoms: He’s unshaven, popping unspecified pills, drinking booze out of those little bottles they stock in hotel minibars. He’s spent some time in an institution, is now seeing a therapist (Annette Bening), and generally comes off less as a lost soul and more like a time-bomb creep. It all has something to do with his wife, Abby (Wilde), who left him six months ago. Or so he says.

But this story is just the first of several morbid twists in a multi-generational, multi-chapter saga of schmaltz, set into motion by a Manhattan bus accident, à la Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret. (Bizarrely, the central theme is that of Lonergan’s follow-up, Manchester By The Sea: the inheritance of grief.) The plot of Life Itself covers an inordinate time frame, from the 1980s to sometime in the 2070s, though Fogelman’s idea of the future looks and sounds exactly like the present day. Not that the overlapping chronologies or the ages of the characters actually add up. Throughout, we are treated to changes in point of view; skips back and forth in space and time; multiple versions of Bob Dylan’s Time Out Of Mind track “Make You Feel My Love” (just like in, uh, the 1998 Sandra Bullock vehicle Hope Floats) and discussions of said song; cutesy-poo dramedy hijinks involving Pulp Fiction-themed Halloween costumes and a dog named Fuckface; and some of the least convincing depictions of comparative literary studies or punk rebellion in the history of cinema.

There is also “The González Family,” a Spanish-language story about a lonely olive oil magnate (Antonio Banderas) who lives vicariously through his working-class foreman (Sergio Peris-Mencheta)—the most compelling and, in some ways, strangest chapter of the film, in part because it feels like it’s set in the 19th century. And that deathless profundity, “the ultimate unreliable narrator is…. life itself,” which is repeated in enough variations to merit a drinking game. The funny thing about this line—besides the fact that it sounds like something a 15-year-old would write and underline—is that it has diddly-squat to do with Life Itself; with the exception of a couple of showy scenes (almost clever in concept, but badly executed), the movie plays its dopey, death-obsessed mawkishness at face value. Unless, of course, the “life itself” refers to the film; its omniscient voice-over keeps telling us that what we’re seeing is romantic, meaningful, or moving, despite ample on-screen evidence to the contrary. Fogelman’s directorial debut, Danny Collins, starring Al Pacino as an aging crooner, was a sentimental but respectable piece of work. Based on the evidence presented here, he should probably stick to playing it straight.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.