From the writer of Sicario comes the terrific, flavorful Hell Or High Water

Hell Or High Water is the kind of movie that makes you fall in love again with the lost art of dialogue, getting you hooked anew on the snap of flavorful conversation. Whenever one of its characters opens their mouth, you’re reminded of how flatly expositional or distractingly florid so much movie dialogue is, even (or perhaps especially) when it’s aiming for the wiseguy patter of Tarantino or Mamet. But in Hell Or High Water, everyone speaks with a plainspoken wit that provides even the most functional of scenes—say, an interview with a bank teller who’s recently been robbed—a charge of pleasure. “Black or white?” asks the officer investigating. “Their skins or their souls?” the victim retorts. These are cops, robbers, and struggling wage slaves, not poets or philosophers. But they all have a way with words, and hearing them exercise it is like guzzling a gallon of water in the desert.

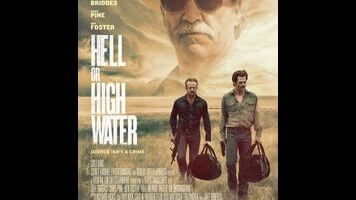

Two men do a good portion of the talking. They are Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner (Ben Foster), brothers heisting their way across sleepy, one-horse Texas. The Howard boys are not your typical bank robbers. For one, they hit only the registers, pocketing a modest few thousand from every score. For two, they’ve targeted a specific bank—a local company with a few branches scattered across the state. The regional nature of the crime spree keeps it out of federal jurisdiction; it falls instead on the desk of grizzled Texas Ranger Marcus (Jeff Bridges, because who does grizzled better?) a few days out from retirement. Marcus spots the pattern and suspects a motive beyond money. He and his partner, Alberto (a terrific Gil Birmingham), take chase.

Audiences have been down this dusty backroad before. The thrill of High Of High Water is in its skillful, offbeat execution. Some of that credit belongs to director David Mackenzie, a Scottish jack of all genres whose been going his own way for years now, dabbling in everything from apocalyptic melodrama (Perfect Sense) to gritty prison drama (Starred Up) to Ashton Kutcher sex comedy (Spread). To the neo-Western he adds a muscular confidence, beginning with a casually virtuosic opening shot that circles the empty parking lots of a depressed small town, before landing on that aforementioned bank teller (character actor Dale Dickey) just as she’s held at gunpoint. The robbery scenes and getaway chases are pressurized pockets of tension, more thrilling for how low-key everything around them feels. (The fact that plenty of the bank customers are packing heat themselves adds an additional edge of danger.)

The film’s other major architect—and arguably its chief visionary—is screenwriter Taylor Sheridan, who penned last year’s hellish cartel thriller Sicario. With just two films, the moonlighting actor, probably best known for his role on Sons Of Anarchy, has developed a singular authorial voice; he twists genre conventions into unpredictable new shapes, turning the Southwest into a moral gray area for cops and criminals alike. Hell Or High Water, like Sicario, betrays a blatant Cormac McCarthy influence: Its downtrodden Texas, an old world whose people and traditions are slipping quietly through the cracks, is no country for old men. That’s conveyed not just in the arc of Bridges’ aging lawman, resisting his one-way trip out to pasture, but in the plight of nearly every ordinary person the main characters encounter during their helixed journeys. Putting a lament for the left behind in the mouth of, say, a cattle rancher outrunning a massive brush fire helps mitigate the didacticism. Or maybe it’s just that hearing these eccentric bit players say anything is never less than entertaining.

It’s quite a feat, orchestrating a crime thriller that feels at once relaxed and urgent, that delivers an endless supply of comic banter without compromising its underlying tone of elegiac regret. The movie luxuriates in downtime, enjoying the company kept with its stars. Pine, as the sensible younger brother, and Foster, as the older, hotheaded ex-con, imply a novel’s worth of Tennessee Williams backstory in their contentious relationship. And in the jokey antagonism between the rangers—Marcus cracking constantly on the Comanche heritage of his partner—Bridges and Birmingham sketch a no less vivid portrait of brotherhood. Viewers may find, in that grand Fugitive tradition, that their sympathies are divided, especially once Hell Or High Water begins pulling its two plot strands together, clarifying its outlaws’ motives, and building to the fatalistic finale it absolutely earns. Never fear, there’s a villain to root against. And to paraphrase one of Sheridan’s best lines, it’s been robbing for 30 years.