Garth Brooks’ comeback album is rooted in midair

Garth Brooks’ name is nearly synonymous with the nouveau country of the early- to mid-1990s, which primed the gravel road to Nashville for a more pop-driven twang. But Brooks was never really just about the music—he was at heart always an entertainer. His outsize, exuberant performances were crucial to his early ascendance, and he made sure that everybody could witness it: Brooks openly supported Pearl Jam’s 1994 federal complaint against Ticketmaster, and in his early tours, insisted on lower, more accessible ticket prices, even in sold-out stadium shows. Brooks’ two most famous songs illustrate the kind of range that endeared him to ropers and made him, if not beloved, at least well known to the mainstream: 1990’s raucous drinking song, “Friends In Low Places,” and 1989’s “The Dance,” a bittersweet love song driven by a simple piano tune. And at every point between those extremes, across eight studio albums and 12 years, Brooks had a goddamn blast.

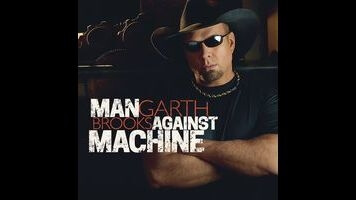

So on his first full-length in 14 years, it’s troubling that Brooks just doesn’t seem to be having fun. Coming out of semi-retirement, it’s understandable that he wouldn’t have wanted to deliver a vintage Garth album—after all, he was 27 when his first hit, “Much Too Young (To Feel This Damn Old),” reached No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Country chart in 1989, and times, and country music, have changed. But neither does his new album, Man Against Machine, capture the spirit of his earlier days, instead trying to court a new generation of country-music lovers with bland, watered-down songs that seemingly throw in some slide guitar as a countrified afterthought. Brooks hasn’t entirely lost his touch—it’s surely no coincidence that the three best tracks on the new album have his name on the co-writing credits. The first of those, “Man Against Machine,” sounds more Chris Gaines than Garth Brooks, belying the rest of the album’s sound. Underpinned by a catchy minor-key tune and mechanized war-cry backing vocals, there’s a vague whiff of patriotism in his reference to an African-American steel-driving legend: “John Henry’s ’bout to blow off some steam / In this war of man against the machines.” It builds to an anthem predicated on the fear that humanity will lose itself to automation—this isn’t the Garth Brooks of the ’90s, not by a long shot, but maybe this is how he sees the Garth Brooks of the 2010s. It’s a visual echo of the cartoonish sunglasses-and-cowboy-hat portrait on the album cover: He’s a country boy, but he’s tough enough to take his schtick to the city. It would be laughable if he wasn’t so earnest.

Brooks does still have a knack for the poppy twang that carried him to fame. Man Against Machine’s standout track, the swinging “Rodeo And Juliet,” is pure old-school Brooks, who, at 52, still has a twinkle in his eye and an infectious exhilaration. Haters of puns won’t even make it past the title, but Brooks sells the cheeseball lyrics with a wink and a grin: “Into our scene of fair Verona / rides a queen from Arizona.” This is the same Brooks who co-wrote the chaotic “Papa Loved Mama” and who gleefully covered Billy Joel’s “You May Be Right.” It doesn’t matter if it’s a little silly, because it’s too much fun to stop.

With the exception of the middling “She’s Tired Of Boys,” which Brooks also co-wrote, the rest of the album veers between maudlin and moralizing, unsure where on the country-pop spectrum it’s aiming for. “Cowboys Forever” attempts to capitalize on the false nostalgia for the Wild West, and the album’s first single, “People Loving People,” is an insipid paean to peace and tolerance. The album’s lowest point is the mawkish “Mom,” a surely well-intentioned but unbearable song about a conversation between God and an as-yet-unborn baby. Nowhere in these mostly forgettable ballads and midtempo tunes does Brooks find the simplicity that he artfully unraveled in early ballads like “The Dance” or “The River”—schmaltzy, sure, but delivered with sincerity and a pretty melody.

For a man who helped lead the charge of bringing country to the mainstream, Man Against Machine relies neither on Brooks’ country backbone nor his love of rock. If he’s just warming up for future albums, there’s some hope buried in these tracks, as long as Brooks takes his own advice from the sloppy “Fish,” a song about leaving the daily grind to just do what you love. Instead of building on Brooks’ strengths, Man Against Machine is firmly rooted in midair.