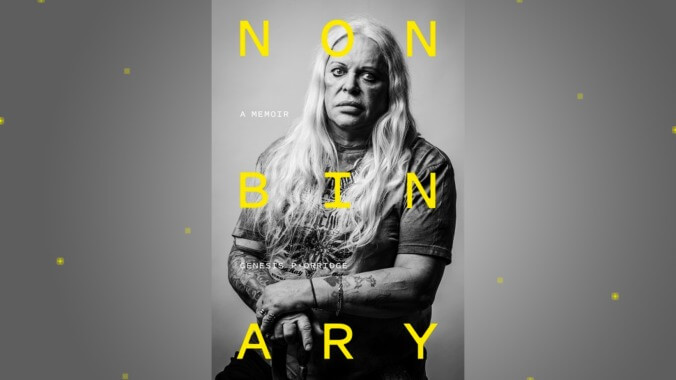

Genesis P-Orridge’s Nonbinary chronicles a singular life and counterculture

The memoir arrives one year after the Throbbing Gristle lead singer's death

There’s a concept prevalent among esoteric traditions called “spiritual transmission” wherein a teacher is said to pass down their state of enlightenment to their student. From Western hermetic groups to certain sects of Buddhism, one could trace the dissemination and evolution of their teachings. One could do the same with the spread of the counterculture in the 20th century, drawing a line from ’90s rave culture back to the psych-rock revolution and the Beat Generation and so on. If any person could be the physical embodiment of that chain of cultural transmission, it’s Genesis P-Orridge.

A musician, writer, and visual and performance artist, Genesis P-Orridge cast a wide shadow over the underground before dying at the age of 70 in 2020 from leukemia. Like their mentor William S. Burroughs, P-Orridge was a gifted raconteur; spend any time in a used bookstore’s counterculture or occult section and you’ll find a book with a Genesis interview in it. For someone so eager to recite their back pages, it’s surprising it’s taken this long for the late Throbbing Gristle singer to pen their memoirs.

Written while P-Orridge was struggling with chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia, Nonbinary arrives a year after the artist’s death. Shifting between “we” and “I” throughout the text, P-Orridge’s first-person voice is theatrical yet accessible—one moment they’re calmly relaying the pleasures of eating unleavened bread with honey, the next they’re describing Edwardian ghosts walking out of their squat with flashlight-under-the-chin relish. The memoir clocks in at 350 pages, which doesn’t seem like nearly enough space to cover P-Orridge’s life and career. Indeed, it takes 140 pages before they begin talking about their work in the performance art troupe COUM Transmissions. Those pre-infamy pages are the most fascinating part of Nonbinary, as P-Orridge describes in great detail what life in postwar England was like.

In one particularly vivid chapter, the author recounts their father’s harrowing experiences at Dunkirk—debilitated by burst ulcers and carried on a stretcher as bombs exploded around him. Anyone who finds the English boarding school system romantic thanks to Harry Potter should have to read P-Orridge’s descriptions of systemic abuse at the hands of teachers and upper-crust bullies (one of whom befriends P-Orridge after the young Genesis stabs them in the belly with a penknife). At times their childhood tales of cortisone-induced near-death experiences or jerking off with a group of neighborhood boys feel plucked from a Burroughs novel.

Much like their Beat idol, P-Orridge has a fondness for recycling stories. For those who’ve read a few P-Orridge interviews in RE/Search books or their long-form pieces in Sacred Intent or Thee Psychick Bible, much of Nonbinary will be familiar. The memoir does double duty as a greatest hits of anecdotes and occult musings. Where the book really shines is how it paints a picture of a pre-digital counterculture. P-Orridge spells out all the ways that art was transmitted back in the day, through channels like pirate radio, cheap printings, and the communion of buying hash from hippies at sketchy bars. P-Orridge also rhapsodizes about the dole, emphasizing how so much art in the U.K. was only possible because artists like themself could pursue their ambitions full-time thanks to weekly welfare checks.

P-Orridge devotes the book’s latter half to chronicling their time in COUM Transmissions, pioneering noise band Throbbing Gristle, Psychic TV, and Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth. Then the satanic panic that caused their exile from England; their lawsuit against Rick Rubin (P-Orridge immediately spent the small fortune they won); and meeting their life partner, Lady Jaye Breyer. The pair would collaborate on their Pandrogyny project, in which both Breyer and P-Orridge underwent significant plastic surgery operations to resemble each other and identify as a single being.

While P-Orridge takes great pains to acknowledge artistic ancestors like Burroughs, they are not nearly so generous when it comes to their bandmates and peers. This is where Nonbinary becomes an uncomfortable read. In Cosey Fanni Tutti’s 2017 memoir, Art Sex Music, the Throbble Gristle co-founder accused P-Orridge of being physically and emotionally abusive—depicting her one-time bandmate and lover as a controlling, manipulative figure who was quick to steal credit from others. At the time, P-Orridge denied the accusations in a New York Times interview with a dismissive “Whatever sells a book sells a book.” P-Orridge presents themself in Nonbinary as more victim than victimizer, surrounded by people who betray or disappoint them. Lovers, bandmates, even their ex-wife go from being kind and gracious on one page to inexplicably turning into complete assholes the next. The immortal words of the character Raylan Givens come to mind: “If you run into assholes all day, you’re the asshole.”

P-Orridge’s Throbbing Gristle bandmates are repeatedly framed as status-obsessed, money-hungry hangers-on. When the artist Monte Cazazza suggests to P-Orridge that “Cosey, Chris, and even Sleazy would be happy to see (Genesis) die onstage,” P-Orridge agrees. P-Orridge implies throughout that they were the heart and soul of the band, never acknowledging that their bandmates later went on to do vital creative work on their own. This erasure goes so far as to entirely omit the band’s re-formation in 2004, with P-Orridge declining to talk at all about its follow-up albums or tours.

The singer’s persecution complex becomes even more apparent when they describe their admiration of Brian Jones from The Rolling Stones and their friendship with Joy Division’s Ian Curtis. P-Orridge describes meeting the former in an early chapter, seeing them as the true genius of the band surrounded by jealous hacks like Mick Jagger. The latter is cast in a similar light as a kindred spirit and close “secret friend” to Genesis, who shared P-Orridge’s frustration with being the misunderstood genius under the thumb of greedy bandmates. “The other six members of our two bands just going through the motions, waiting for their two lead singers to get over their little art kick and become the usual moneymaking spectacles again,” P-Orridge writes, sharing a plan the two singers had to dump their respective bands onstage at a future gig in Paris that would never come to fruition.

For someone who has written moving passages about collective effort and the need to question convention, P-Orridge was awfully fond of the “great man” theory when it came to making art. While P-Orridge is right to feel proud of themself, considering the depth and breadth of their accomplishments, the self-aggrandizement gets wearying and at times absurd: When P-Orridge talks about their Pandrogyny work with Lady Jaye, they grandly state how they saw the rise of trans culture coming—intimating that the work they and Jaye did helped speed it up. It’s ironic that P-Orridge casts a skeptical eye on Aleister Crowley in their book considering how prone they are to making the same kind of sweeping, aeon-ushering pronouncements that the Great Beast loved to dish out. Forget sympathy—this devil could use a little humility.