Genius makes the old-fashioned fresh again, at least for awhile

There’s a reason we make movies about tempestuous artists. Their outsized and larger-than-life personalities are a natural fit for the big screen. Quiet, reserved types don’t elicit the same reaction: It’s exciting to depict the life of Ernest Hemingway, less so homebody Don DeLillo. In Genius, an account of novelist Thomas Wolfe’s literary career as seen through the eyes of his editor, Maxwell Perkins (and based on the biography Max Perkins: Editor Of Genius), the standard biopic filter of seeing a spitfire soul through the lens of a more reserved and relatable associate succeeds to a greater degree than usual. It’s a case of the straight man getting his due, a film praising discretion as the better part of valor—to tweak the old gendered expression, behind every great writer lies a great editor.

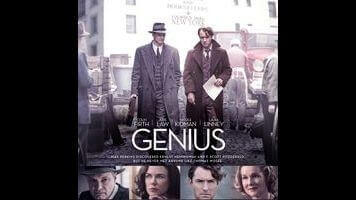

Genius wants to show its audience how the literary sausage gets made. Here, that means following the life of Perkins (Colin Firth, who can do this kind of role in his sleep), a quiet and proper family man and editor at Scribner’s, though already a giant in the industry by the time the film begins in 1929, due to having discovered and edited both F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway. (Both men make appearances in the film, the former via an understated but excellent Guy Pearce, the latter as a more traditionally garrulous interpretation from Dominic West.) Perkins meets Wolfe (Jude Law) and agrees to publish his first novel, only to discover that the flamboyant writer brings with him an intimidatingly overdriven creative process. When the massive pile of papers that would become Wolfe’s debut novel, Look Homeward, Angel, are first plunked onto Perkins’ desk, he apprehensively murmurs, “Double-spaced, I hope?” We follow the two men as they struggle to edit Wolfe’s first book and then spend years chopping down his second, even as the author continues to produce endless new pages throughout the ordeal.

Inevitably, there comes a reckoning, followed by a falling out, and the two men part ways, with Wolfe abandoning Perkins and Scribner’s for a more lucrative deal. The movie carries us through all of this with the usual array of significant moments, jazz-inflected montages of the two men working and butting heads over the business of art and the unfortunately marginalized roles of the women in their lives. Nicole Kidman dazzles, perhaps a bit too brightly (she shines like a silent-movie star, even in the midst of soot and smoke from train exhaust), as Wolfe’s long-suffering and adulterous lover, Aline Bernstein. And Laura Linney is given little to do in her too-brief scenes as Max’s wife, Louise. But the meat of the narrative is the way these two men defined one another. While almost every scene is boilerplate great-artist biopic (Wolfe’s the live wire who pulls Perkins out of his shell; Perkins is the honest family man who eventually makes Wolfe realize the cruel immaturity of his behavior), screenwriter John Logan (Gladiator, Skyfall) keeps things lively, his fleet wit enlivening the formulaic nature of the story, much as he does in another period piece, Penny Dreadful.

Or at least, he does at first. Viewers experience the rise and fall of this artistic relationship the same way the characters do: It’s fun on the way up, dreary on the way down. A turning point comes during a visit to a jazz club, where Wolfe’s analogy of his writing to the black musicians playing onstage comes across more like clumsy racial appropriation than inspired invention. From there, things begin to deflate. The mercurial Wolfe eventually leaves Perkins, the writer’s ego outstripping his loyalty. Law imbues Wolfe with a touch of The Talented Mr. Ripley’s Dickie Greenleaf, a charismatic center of attention who carries everyone along in his wake. Perkins, the “only real friend” Wolfe says he’s ever had, feels the sting of this rejection. We know this because the film resorts to having Pearce’s Fitzgerald explicitly tell us so, as the back half loses itself in soggy cliches that even Logan’s dialogue can’t rescue. (When Wolfe’s firing of Perkins is preceded by a shot of Law, standing in the rain, looking resignedly up at the Scribner’s sign, the entire narrative feels beaten down by that symbolic weather.)

Thankfully, for us and the movie, Wolfe dies before we have to sit through any scenes of reconciliation or last-act lesson-learning. First-time helmer Michael Grandage is an actor’s director in the Sidney Lumet vein (and took a similar path through theater en route to feature film), forgoing visual razzle-dazzle in deference to capturing his actors’ performances from the most effective distances. The film is never more alive than when Wolfe and Perkins are arguing over the nature of art—Wolfe’s logorrhea is a perfect counterpoint to Perkins’ belief in minimalism, and the fire-ice dynamic develops a buddy-picture ease over the course of the film. Genius may eventually be a little too comfortable with its own formula (unsurprising, considering its full-throated endorsement of Perkins’ traditionalist mien), but in its early going, it captures a little bit of the magic of artistic creation—and like any good creation myth, the best stuff happens in the beginning.