Geoff Johns reckons with his DC Comics legacy in Doomsday Clock #10

What is the point of Doomsday Clock? It can be read as a treatise on hope and optimism overcoming despair and darkness in the superhero genre, but it really leans into the despair and darkness in the execution. If it’s supposed to pave a path for the larger DC Universe, the paving is taking a very long time. After a year and a half, the rest of DC’s line hasn’t shifted anywhere closer to the events of the miniseries, which has slipped from shipping every month to every two months to every quarter. The creative team is succeeding if the point of Doomsday Clock is to cash in on Watchmen’s popularity to drive interest for yet another continuity-juggling event comic, but as the series continues, a fascinating new dimension emerges in the shadow of real-life events.

No, I’m not referring to anything involving the USA and Russia, a political conflict integral to the Doomsday Clock plot. I’m referring to writer Geoff Johns’ relationship with DC Comics and Warner Bros, which is in a very different place now than it was when the seeds for Doomsday Clock were first planted. DC Universe Rebirth #1, the one-shot that shut the door on the New 52 and brought Watchmen into the core DC Universe, was released in May 2016. Two months later, Johns would be named President of DC Entertainment. Doomsday Clock #1 was released in November 2017, and eight months later, his tenure as President was over. The success of the Wonder Woman movie was rapidly spoiled by the failure of Justice League, and in the shadow of Marvel Studios’ unprecedented success, the weak performance of a movie starring Batman, Wonder Woman, and Superman doomed Johns in his leadership position.

Johns excels as a creator, and once he left his roles as President and Chief Creative Officer, he was quickly rewarded for his writing. He co-wrote the story for the surprise smash Aquaman, and his first writing credit for a DC feature film grossed over a billion dollars worldwide and helped rehab the studio’s image. But reading Doomsday Clock #10, you get the impression that Johns doesn’t look back at recent years fondly. This issue is steeped in resentment and regret, with Johns emphasizing the dark side of Hollywood fame and the mistakes that were made when DC launched the New 52 and used it as a template for its cinematic efforts. There isn’t a one-to-one correlation between reality and the events in this superhero comic, but if Johns is going to introduce the idea of a “Metaverse,” in this issue, he’s asking readers to ponder how the story speaks to the circumstances of its creation.

Much of Doomsday Clock plays like standard DC vs. Watchmen fanfiction, but the book has become much more compelling as it builds a metanarrative about being the architect of a superhero universe. Johns has felt the rush of leaving an indelible mark on IP that reaches a massive audience, but he’s also experienced the backlash when that audience rejects his ideas and costs him his job. Doomsday Clock #10 is a tragedy about having the power to change the universe and discovering that you’ve used it to create something worse. Like Johns, Doctor Manhattan sees how the “Metaverse” has been altered in the past and decides that he wants to be part of that legacy. Manhattan feels more connected to Superman in the new timeline, but the “Metaverse” fights back, first by bringing back Wally West, then rallying all of the world’s heroes against a common foe.

One of my initial concerns with the Doctor Manhattan revelation in Rebirth, beyond the ethical minefield that comes with using any Watchmen characters, was the idea that an entirely unrelated property would be blamed for DC’s publishing missteps. Implying that Watchmen’s influence was responsible for the New 52 didn’t jive. A line can be drawn from Watchmen’s bleak take on superheroes to the grim and gritty superhero comics of the ’90s, but the New 52 was far more beholden to the latter, particularly on the art side. But as Doomsday Clock continues, my interpretation of the Doctor Manhattan arc significantly changes. He’s stopped being an avatar of the Watchmen universe and has instead become a stand-in for writer Geoff Johns, who uses the character to look at the rush of altering superhero universes and the agony of screwing them up.

DC Universe Rebirth #1 revealed that Doctor Manhattan caused the New 52 by altering the timeline, and three years later, Doomsday Clock #10 reveals how and why he changed it. After the last issue’s big showdown on Mars, the miniseries switches gears to move in an introspective direction for #10, which is split between three storylines: The primary thread is Doctor Manhattan arriving in the core DC continuity, seeing how it is changed over time, and choosing to alter it himself. The second thread follows Carver Coleman, an aspiring actor in the Golden Age of Hollywood whose life is changed when he meets Doctor Manhattan. The last story is the myth of Superman, told over and over again with slight variations. These all come together via Doctor Manhattan’s time-bending perspective, jumping across the timeline as he tries to acclimate to the curious temporal dynamics of this dimension.

The creative team of Doomsday Clock has been working together for over a decade, beginning with Geoff Johns’ run on Action Comics before The New 52. Artist Gary Frank’s work strikes a balance between classic superhero exuberance and more modern grit, and Brad Anderson’s coloring heightens those tonal shifts while matching the sharp detail of the linework. He makes powerful use of red and blue to build up to the life-changing meeting between Doctor Manhattan and Carver Coleman, and his color palettes play a vital part in distinguishing between different superhero eras as Doctor Manhattan sees Superman’s story change with each timeline shift. The last two issues have been especially strong showcases for Frank and Anderson’s versatility, with #9 giving them the opportunity to present large-scale superhero spectacle while #10 zooms in on specific characters for a story that still has huge implications, but is visually more contained and intimate.

The continuity manipulation of Doomsday Clock #10 is total nonsense. Naked blue god-man sees that imaginary timeline has been repeatedly changed, decides to stop railroad engineer from grabbing magical lantern and changes timeline even more. Along the way naked blue god-man discovers that this superhero universe isn’t part of the Multiverse, but responsible for shaping all of those parallel worlds. It’s a “Metaverse” that rearranges the Multiverse every time it changes, and by making his own mark on the timeline, naked blue god-man becomes the villain that the heroes need to destroy. Doctor Manhattan is not all that different from villains like the Anti-Monitor and Extant who have previously changed continuity, but he carries the gravitas of Watchmen and everything that book represents, from the artistic liberty that makes it a seminal superhero text to the corporate greed that makes it a prime example of the industry’s exploitation of creators.

Scenes from Carver Coleman’s Nathaniel Dusk film, The Adjournment, have been sprinkled throughout Doomsday Clock, serving a similar function as the Tales Of The Black Freighter interludes in Watchmen. Nathaniel Dusk is a private investigator character introduced by DC Comics in the mid 1980s and erased from continuity after Crisis On Infinite Earths, and Johns uses Dusk to integrate the relationship between comics and film into the Doomsday Clock narrative. Warner Bros. made its name with gangster films, and by incorporating an established DC character into the movie studio’s Golden Age, he draws a cinematic parallel to the comic-book Golden Age begun by the debut of Superman.

Hollywood is at the foundation of Geoff Johns’ comic-book career. He broke into the entertainment industry as a production assistant for Superman: The Movie director Richard Donner, who would join Johns as the co-writer of Action Comics in the mid ’00s. Johns would build his career as a power player at DC Comics, revitalizing dusty properties and penning hit crossover events that reshaped the entire DC Universe, and that knowledge would prove very useful to Warner Bros. as superheroes surged in popularity in both film and television. Like Carver Coleman, Geoff Johns got ahead in Hollywood because superheroes helped him see the future, but once you reach a certain level of power, you become a target. Carver is killed by his mother when she bashes his skull in with his Academy Award. Johns is fired by DC’s parent company after being set up for failure with a troubled production.

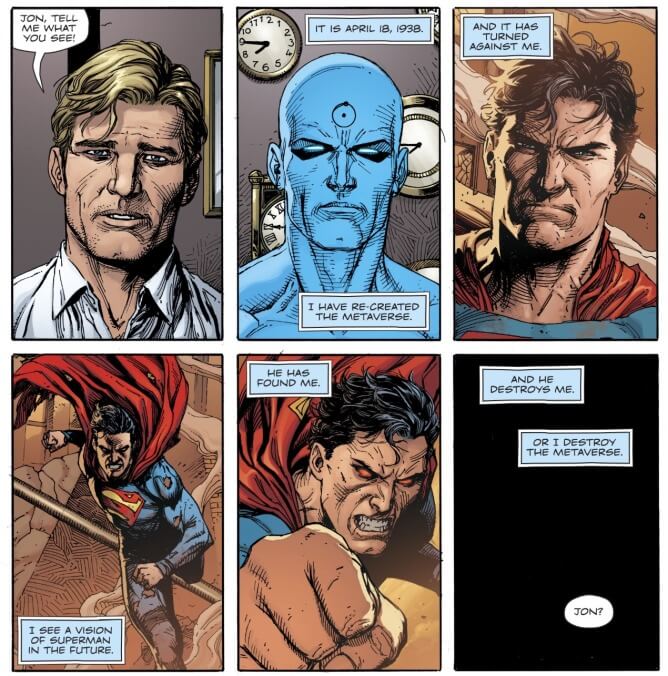

The roots of that troubled production start at Superman, and Zack Snyder’s Man Of Steel kicked off DC’s cinematic universe with a bleak, cynical worldview that was more distinctive than Marvel Studios’ work, but also not as appealing. As the first of his kind, Superman is at the core of the DC Universe, even if he’s not DC’s most profitable character (that’s Batman). There’s something particularly intoxicating about changing Superman, but if you go too far, there’s one hell of a come down. DC Entertainment felt it after Man Of Steel, and Johns felt it after the New 52. With all this context in mind, this narration from Doctor Manhattan gains autobiographical implications that makes Doomsday Clock more personal: “I have recreated the Metaverse. And it has turned against me. I see a vision of Superman in the future. He has found me. And he destroys me. Or I destroy the Metaverse.”

It feels like DC has turned against Johns in the past year, largely because of how it’s handled Wally West in the pages of Heroes In Crisis. Doomsday Clock #10 was released on the same day as Heroes In Crisis #9, giving readers some serious whiplash in how they present Wally West’s function within the DC Universe. In Doomsday Clock, Wally is universal antibody, fighting the Doctor Manhattan infection by remembering the world before the New 52. He’s situated as a beacon of hope, but in Heroes In Crisis, his trauma has driven him to mass murder. It’s a message completely opposed with what Johns is trying to say in Rebirth and Doomsday Clock, and seeing DC diminish Johns’ work while its still in progress is fitting given the book’s relation to Watchmen, a comic with a legacy steeped in conflict between publisher and creator.