Getting started with Brian Eno, glam icon and art-pop pioneer

Pop culture can be as forbidding as it is inviting, particularly in areas that invite geeky obsession: The more devotion a genre or series or subculture inspires, the easier it is for the uninitiated to feel like they’re on the outside looking in. But geeks aren’t born; they’re made. And sometimes it only takes the right starting point to bring newbies into various intimidatingly vast obsessions. Gateways To Geekery is our regular attempt to help those who want to be enthralled, but aren’t sure where to start. Want advice? Suggest future Gateways To Geekery topics by emailing [email protected].

Geek obsession: Brian Eno

Why it’s daunting: As rock brands go, Eno is one of the most rarified. Although Brian Eno made his first mark in rock as the keyboardist on the groundbreaking first two Roxy Music albums, 1972’s Roxy Music and 1973’s For Your Pleasure, he left to pursue his mad-scientist explorations into severe, abstract art-pop. From there, he took a quantum leap; his pioneering work in ambient electronic music in the ’70s opened up whole worlds of sound for successive generations of aural explorers. At the same time, it placed him far above the mundane pop world, even as he entered into fruitful collaborations and production work with everyone from Talking Heads to U2 to the no-wave radicals of 1978’s epochal No New York compilation. His prolificacy has resulted in a sprawling catalog that often doubles back on itself stylistically, a solipsism that neatly mirrors some of the experiments with feedback loops he helped spearhead 30 years ago. It makes for an intimidating body of work, much like his austere image.

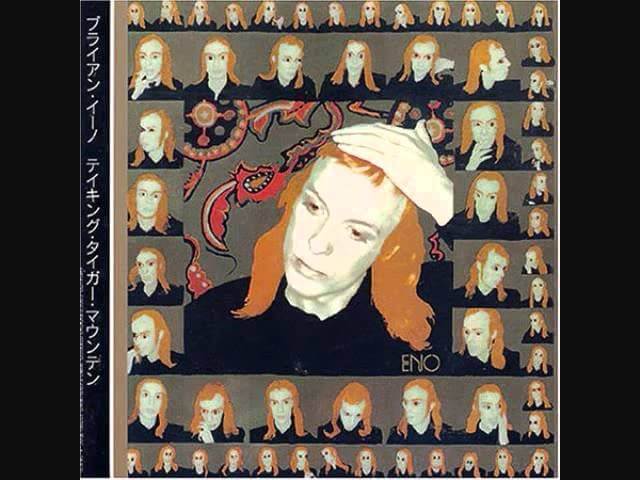

Possible gateway: Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)

Why: Eno’s second solo album, 1974’s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) is the sound of the frustrated Roxy Music sideman firing on all cylinders. And what a wheezing, slashing, elaborate contraption of cylinders it is: Settling into a semi-solid lineup of glam and prog backing musicians (including Roxy Music guitarist Phil Manzanera and Soft Machine’s Robert Wyatt on percussion and backing vocals), Taking Tiger Mountain makes both glam and prog seem quaint by comparison. From the clanging, robotically sentimental precision of “Burning Airlines Give You So Much More” to the Pink Floyd-on-a-hot-plate skittishness of “Third Uncle,” the album straddles everything Eno accomplished during his long ’70s peak—up to and including ambient music, which is presaged by the disc’s impressionistic, mantra-like title track.

Next steps: Few albums burst out of the gate with as much force, assurance, and vision as Eno’s solo debut, 1974’s Here Come The Warm Jets. The riff of the opening song, “Needles In The Camel’s Eye,” is like a can opener to the skull. Nodding to The Velvet Underground and krautrock while encasing those nervy sounds in plastic, the song sets the tone for Warm Jets’ minimalist pulse, clean edges, and Eno’s otherworldly vocals. The album ultimately doesn’t cohere with the same focus and accessibility as Taking Tiger Mountain, but it comes in a close second.

Another Green World follows Taking Tiger Mountain by a mere 10 months; his momentum at last uncorked, Eno began feverishly laying out the template for countless art-rock, post-punk, new-wave, indie-rock, and even goth bands to follow. In spite of that wide influence, there’s a narrow formalism to Another Green World as Eno started to curl inward. Using a Tarot-like methodology called Oblique Strategies to help guide the creative process, he let the album’s stark, shadowy, mostly instrumental silhouette take shape according to the whims of fate—not to mention guests such as John Cale, Phil Collins, and King Crimson’s Robert Fripp.

The relatively unsung entry in Eno’s inaugural five-album stretch is Before And After Science. Torn between Eno’s textural and melodic tendencies, it’s a murky disc that’s lush with hooks and angularity. This is where Eno’s studio work—most notably Devo’s debut, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!—began to influence his own output, such as in the Devo-like “King’s Lead Hat.” Before And After Science also sounds the most dated of Eno’s ’70s releases. Still, it’s a puzzling, yet inviting album.

Of all of Eno’s collaborations, his most lucrative and mutually rewarding was with David Byrne. After co-producing Talking Heads’ More Songs About Buildings And Food and Fear Of Music, he became an integral contributor to the group’s 1980 masterpiece, Remain In Light. That relationship spun off into My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, the 1981 album billed as Brian Eno and David Byrne. Suffused with spectral electronics, jittery chants, disembodied samples, and the Afropop underpinnings first heard on Remain In Light, Bush Of Ghosts is as much of a polyglot wonder today as it was over 30 years ago.

Where not to start: Eno’s knack for collaboration first bloomed with an unlikely partner, Robert Fripp. At the time of the release of Fripp & Eno’s 1973 debut, (No Pussyfooting), Fripp was a renowned prog virtuoso, while Eno was adding his luster to one of glam’s leading lights. The odd union resulted in some breathtaking excursions into early symphonic ambience, and it pushed both visionaries to tinker with their instruments both technically and conceptually. That said, this isn’t the best place for Eno newcomers to start—nor is his vast body of ambient work itself. Inspired by Erik Satie’s idea of, for lack of a better term, musical wallpaper, Eno began his career as an ambient artist with 1975’s Discreet Music. From there, 1978’s Ambient 1: Music For Airports dovetailed with Eno’s growing interest in the utility of music both as a postmodern statement about the colonization of the human psyche by background sounds, and a pleasant, mellow listen. The work is stunning and essential, but Eno’s art-pop records are a better way to become acclimated to his unique sensibility.