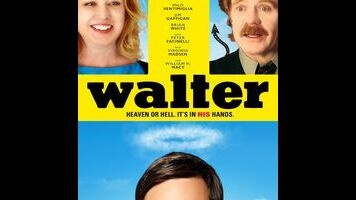

Ghosts, religion, and quirky mental illness blend poorly in Walter

Throughout Walter, the title character (Andrew J. West), who believes that he decides whether each living person in the world will go to heaven or hell, is haunted by a ghost named Greg (Justin Kirk). Greg sardonically presses Walter for a judgment after the fact, and at one point late in the film, Walter tries to run away from him. Greg warns that it’s a pointless exercise to run away from a ghost, which seems consistent with the movie’s depiction of ghost behavior to this point. But the movie shows Greg running after Walter anyway, in apparent belief that—logic aside—there’s emotional catharsis in a slow-motion foot chase scored to the surging strains of imitation Mumford & Sons.

This mismatch of quirk and emotion brings to mind a question raised by Walter’s therapist (William H. Macy) earlier in the movie: “What kind of crazy are you?” It’s meant as the kind of cutesy dialogue that screenwriters give to therapist characters to show how unconventional, irreverent, and relatable they are. What’s not to love, after all, about a therapist who calls a mentally unbalanced man crazy to his face? But it’s also an appropriate response to both Walter the movie and Walter the ridiculous construct of a movie character.

The former places the audience in the hands of the latter when the movie opens with Walter’s narration. He quickly explains that he’s another son of God (not the one with the beard, he clarifies) and, as such, must make the heaven/hell call about every person he meets. In part because the movie unfolds from Walter’s point of view, it offers no particular religious justification for conflating God’s son with the task of eternal judgment. (There is a heavy-handed thematic rationale, to be revealed later.)

Walter’s sacred duty supposedly requires that he live simply, at home with his mother (Virginia Madsen), maintaining a low-level job taking tickets at a movie theater, which places him in steady contact with a variety of people to classify as bound for heaven or hell. Fitting for a movie about a movie theater employee, director Anna Mastro provides shorthand for Walter’s life by combining Wes Anderson miniaturist perfectionism (Walter’s possessions are neatly laid out; he even has a tiny cleaning kit for keeping the ticket-stub box tidy) with Darren Aronofsky-lite close-ups of ritualized preparation for a day’s work.

When Greg starts appearing to Walter, disrupting his carefully calibrated routines, the apparition also sends the movie scrambling from oddball character study to melodrama. Along the way, it hits plenty of padding; Walter was expanded from a short also written by credited screenwriter Paul Shoulberg. Those origins are clear, as even multiple versions of the same scene (Greg surprises Walter out of nowhere; Walter gets flustered and frustrated; Greg disappears) and some strange detours (like a single point-of-view break that follows Walter’s mother to the grocery store) can’t get the story across the 90-minute mark.

Walter still feels plenty long, though, thanks to a premise that’s both elaborate and underdeveloped. Mastro melds together memory, fantasy, and reality with some music-video-style invention, but the script undermines her efforts with its earnest but painful emoting, as when Walter’s love interest Kendall (Leven Rambin) jumps straight from a total lack of characterization to insights like “we’re all broken, Wally, and maybe that’s okay.” Maybe it is okay, but much of Walter’s behavior resembles, at very least, a movie version of mental illness, only to have the story reclassify it as a coping mechanism. This unwittingly makes the character seem as affected as any Sundance stereotype—and the movie disturbing for all the wrong reasons.