God won't shut up as Good Omens pops opens "The Book"

Look, it’s not Frances McDormand’s fault.

McDormand is an immensely talented performer, of course, capable of bringing even the most unlikable characters to some flavor of sympathetic life, and if you were casting God in anything, she’d be a hard pick to beat. It’s not her fault that Good Omens seems bound and determined to stick her with roughly twice as much narration and exposition as any given scene warrants—and even then, she’s able to make the most of lines like the wry “Most books on witchcraft are written by men.” It’s just that, nearly every time her God cuts in to spell out some plot point in the show’s second episode, it’s one that’s already been covered by the visuals or the dialogue—one of those nifty tricks you can pull off when you’re working in television, instead of books.

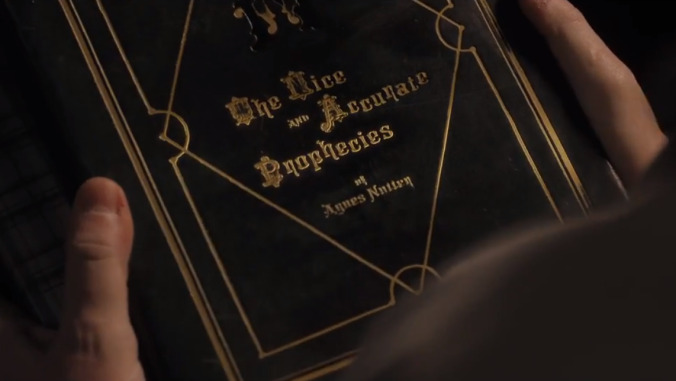

To be fair to Our Heavenly Biggun, though, that obvious second-guessing of the audience’s ability to follow along doesn’t confine itself to the show’s divine narration. It’s all over the place in “The Book,” whether it’s the two visual reminders inserted to make sure we understand that the woman running the paintball game management course in modern day is the same Sister Mary Loquacious from “In The Beiginning,” or—in the episode’s most baffling moment—the repetition of one of Agnes Nutter’s perfectly accurate prophecies literally a single minute after it was first read in its entirety (with accompanying on-screen text!) in a previous scene. Was screenwriter Neil Gaiman really expecting audiences to glower confusedly at the first reference to Apples, 1980, “Jobbes,” and investments, only to have their faces clear up into joyful smiles when the puzzle was spelled out for them 60 seconds later? And the less said about the show’s soundtrack—and especially those damned (but gentle!) acoustic guitars that kick in every time Adam and the idyllic Tadfield kids show up on screen—the better.

All of which is a shame, because when “The Book” gets out of its own way, there’s still a lot of fun to be had with its various apocalyptic shenanigans. The opening scene—in which Jon Hamm digs even deeper into his “smiling asshole manager” take on the angel Gabriel—is an especial highlight, with Hamm’s happy cries of “Pornography!” highlighting just how dopey the forces of Heaven actually are. There’s also the very funny punchline to Agnes’ execution—either premeditated mass murder, poetic justice, or both, depending on how you feel about ungrateful, filthy peasants—and the snide commentary from Josie Lawrence’s Agnes to her persecutor, Thou-Shalt-Not-Commit-Adultery Pulsifer.

The actual plot of the episode, meanwhile, mostly concerns itself with those two enemies’ descendants, tracking Anathema Device (Adria Arjona) and her efforts to hunt down the Antichrist, and Netwon Pulsifer’s efforts to…hang out with Michael McKean? Not that we can blame him, but Newt’s adventures in job-seeking end up serving as little more than table-setting, establishing that he’s bad with computers, kind of a pushover, and otherwise pretty bland. (Ditto our brief introduction to the horseman War, whose major power appears to be smirking at people for fun and bloody profit.)

The meat, as ever, is Aziraphale and Crowley, who go on a road-trip/date out to the countryside in order to try to track down records of Adam’s “birth.” The soul of the show remains the interplay between these two ostensible opposites, whether it’s David Tennant rolling his (serpentine) eyes at Michael Sheen’s declaration of the Velvet Underground as “bebop,” or the way Aziraphale silently begs Crowley to use magic to fix his paintball-afflicted coat. The content of the scenes isn’t terribly important—which is good, because they accomplish bugger all, aside from nearly killing Anathema and stealing her family’s most precious heirloom—but they play off each other so well that you can’t help but find yourself wishing that this whole Armageddon thing would cool off for a minute so we could just get a Sheen and Tennant hang-out show.

Speaking of the End-Times: They are certainly a-endin’. As the episode comes to a close, we’re less than a day out from the end of the world, Adam seems to be having some troubled sleep as his hour comes ‘round at last, and Aziraphale gets a very unsettling reminder about his cocoa. The Antichrist has been found—or at least phoned—and it remains to be seen whether anybody can stop him. Or, more importantly, if the show can finally start shutting up long enough to make stopping the end of the world even seem like it’s worth it.

Stray observations

- So far, the scenes with The Them have been less obnoxiously cloying than one (i.e., I) might have worried, mostly because the young actors have better comic timing and presence than you might automatically assume. (Amma Ris is especially good as Pepper.)

- In terms of changes from the book, the biggest alteration is that Aziraphale finds Adam much earlier, giving this episode its big cliffhanger ending moment. (Also, the kids use a tire swing as a torture implement, instead of a dunking stool.)

- Cannot over-emphasize how awful the CGI looks when Crowley shows his “real” face.

- That bit where he pins Aziraphale against the wall is just begging to be GIF fodder, though, no?

- Tennant’s best work in the episode is selling the “talking to plants” bit; it’s a weird little digression, but he makes it work.

- Oh, and the slow-burn on the “Ducks!” joke.

- All of the prophecies that pop up on the screen (except the Apple one, since Steve Jobs was off in NeXT land in 1990) are lifted straight from the book.

- I’m just going to assume Newt knows Sgt. Shadwell is actually Michael McKean and wants to get his autograph, because otherwise, his immediate decision to sign off of a vaguely misogynistic crusade would be kind of hard to swallow.

- British-isms: Jeffery Archer is a disgraced conservative politician who also wrote novels with names like A Matter Of Honour; Dick Turpin is an English folk hero and famed horse thief, whose significance to Newton’s car will presumably be explained when someone actually asks him about it.

- Ineffable count: 0. This episode was entirely effed.