Godard pits a noir detective against a proto-HAL

Every day, Watch This offers staff recommendations inspired by the week’s new releases or premieres. This week: For The A.V. Club’s Artificial Intelligence Week, we’re focusing on sentient computers and computer programs, a.k.a. our future overlords.

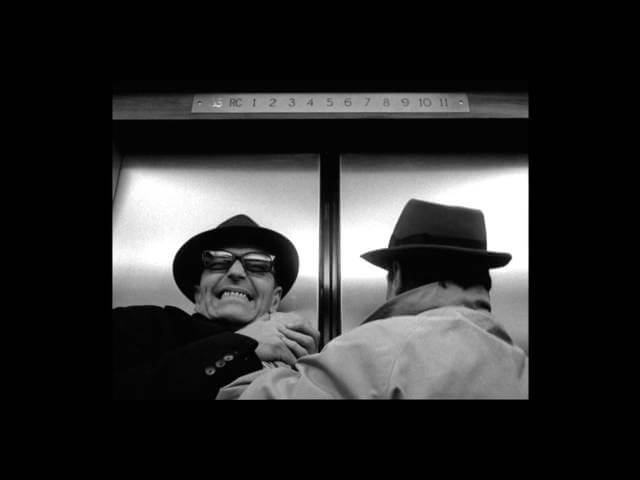

Alphaville (1965)

Playfulness has always been one of the most endearing—if easily overlooked—qualities of Jean-Luc Godard’s work. In recent years, especially, it’s become easy to miss the French filmmaker’s sly sense of humor, obscured as it often is by the sheer density of images, information, and polemical outrage he packs into his essayistic features. That’s probably why casual Godard fans received last year’s Goodbye To Language so warmly (it has a dog and fart jokes!) and why they tend to gravitate to the “cooler,” simpler films he made in the ’60s. Alphaville, Godard’s ninth feature, isn’t as popular as Breathless or Contempt, to name two other milestones of his New Wave period. But it’s surely one of his funniest, most entertaining movies—a stylish pastiche whose typical headiness doesn’t detract from the joy Godard plainly takes in mashing together disparate genres.

Noir is the first of said genres to reveal itself, as Alphaville opens with a secret agent (Eddie Constantine, reprising an iconic role he played in several earlier French thrillers) traveling to a shadow-drenched Paris, where he adopts the unconvincing disguise of a photographer on assignment. As it turns out, the city isn’t what it seems to be either: Paris plays not itself, but the futuristic backdrop of the title, a dystopian metropolis where all art has been banned, all displays of emotion are illegal, and logic reigns supreme. The ruler of this oppressive society is Alpha 60, an advanced supercomputer that lectures the populace through a citywide speaker system and in the guttural groan of a mechanical voice box.