Robert Duvall looks back on The Godfather, and the offer he refused for Part III

The Oscar winner reveals what he learned from Coppola and Brando and dissects his complicated relationships, onscreen and off, with the Corleones

The Godfather trilogy featured a murderer’s row of incredible, even iconic actors, but it’s Robert Duvall who buried all of the bodies in the first two films. Playing Tom Hagen, Duvall was the outsider as insider, wrestling with loyalty to the family that took him in as a teenager as well as the arm’s length distance required while Michael Corleone consolidates and strengthens the family’s criminal empire. That tension feels palpable in Duvall’s performance, and it encapsulates the relationship between legitimate enterprises, the Corleone empire, and the underworld bosses they fight for control.

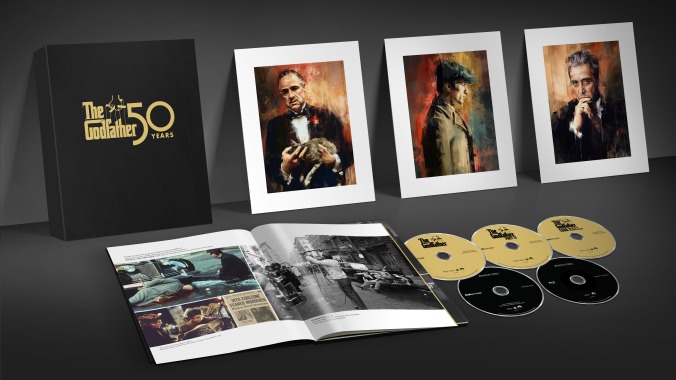

Duvall recently spoke with The A.V. Club about his work on The Godfather, which commemorates its 50th anniversary this month with a release on digital and on 4K UHD. The Oscar-winning actor discussed his relationships on and off screen with members of the Corleone family, the differences between his acting technique and theirs (in particular, Marlon Brando’s), and his relationship with director Francis Ford Coppola before and after the making of The Godfather Part III, which he famously passed on. Duvall also reflected on the lessons he took from Coppola and other luminaries as he moved into directing himself.

The A.V. Club: It’s hard to say that any character in The Godfather is better written than any other, but Tom Hagen is just so brilliantly crafted—so knowledgeable and skilled, but just on the outside of everything. As an actor, was there anything that you did to maintain that little distance from the rest of the family?

Robert Duvall: As an actor and a character both, you can’t step over the line. He’s an adopted son, so he is a member of the family, kind of; maybe not a thousand percent, but he’s very important to the family. And as an actor, you can’t step over that line either. You have to kind of keep yourself in the background a little bit and then be called upon when needed.

AVC: I understand that at least some of the rehearsal process involved the family sitting down for dinner. What did that teach you about Tom, whether it was where you sat at the table, or just your interactions with the actors playing the rest of the Corleones?

RD: Well, the thing I remember most was that with [Marlon] Brando at the head of the table, the family made sense because Brando was like the head of the family. And in life he was for the most part an actor that so many young actors looked up to in a very intense way. He was “the guy,” so to speak, and we all felt that about him, each in an an individual way.

AVC: The 1970s was just one masterpiece after another, but was there any sense while filming The Godfather that it would have this longevity and legacy?

RD: Well, I’ve only felt that twice. I felt that about a third of the way through Godfather I. I said, “we’re really doing something I think pretty special here that will live on for a long time to come.” I felt that we were making a really important film.

AVC: Do you have a favorite scene from the film?

RD: Well, I guess thinking of the stuff I was in, when I had to tell Brando about Sonny’s death, that was pretty important. And when I went to see the head of the studio, the Woltz guy. He yelled at me and I kind of held my ground against him, I can remember that. But it was a wonderful part to play. Because as an adopted son, you can’t step over the line. And as an actor, I couldn’t step over the line, I was always a little bit behind things.

AVC: You mentioned the reputation that Brando brought to the set was so exciting and intimidating—

RD: No, not intimidating. It always felt equal.

AVC: Well, he obviously had a well-documented approach that was unique. He was such a great actor, and yet he also used cue cards sometimes for his dialogue. Were there any adjustments you had to make or anything that tested your approach while you were working with him on scenes?

RD: No, not really because I tried that once. I didn’t go that route. I felt that if you know your lines perfectly, you can still be very spontaneous. He did that because he claimed it made him spontaneous, but I think it was partially that and partially laziness.

AVC: Francis admits in the commentary for the original cut of The Godfather III that the film suffered from your absence, and you’ve said you have no regrets about passing on the film. Was it a business decision that you both understood? And was there a reconciliation, because you worked together so many times?

RD: Oh no, we stayed friends and he helped me with the editing of certain things I did. I haven’t talked to him much lately, but for a while there we talked a lot and conversed a lot definitely after that. Definitely, definitely. I visited his vineyard and him and so forth. He’s an interesting guy, interesting guy.

AVC: You worked with him four times. Which of those did you enjoy the most, whether it was the process of making it or just the end result of the film?

RD: Both. Both. I enjoyed Apocalypse Now, working with him, but also I enjoyed the Godfathers I and II a lot, working with him, definitely.

AVC: It’s so interesting looking at your ’70s film work. It seems like you were hiding your Southern accent until Tender Mercies, and that has been a different persona that you’ve carried forward. Did you have to conceal that side of you, or was that a product of the opportunities you were getting?

RD: No, I knew a wonderful young lady that once told me that “you can do rural, but you can do urban, too.” But I saw a film two nights ago that I had forgotten about called Convicts. It’s one of the best performances I’ve ever given. It definitely was very, very rural, by Horton Foote. You see, when I was coming up, Coppola and Horton Foote from Texas were very helpful in getting my career going and keeping it going. And then Ulu Grosbard, the film and stage director on the East Coast, I did like four theater pieces with him in one film. But whenever I’d get a script that I wanted an appraisal of, I would send it to Ulu and he would read it right away. So those three people were very instrumental in my developing as an actor.

AVC: One of my favorite films that you made is The Apostle. It’s one of the best movies I’ve seen about faith, and it’s such a remarkable film overall. Are there lessons that you’ve taken from filmmakers like Coppola when you tell your own stories?

RD: Yeah, you take from them. I can’t put my finger on concrete things pertaining to that, but you definitely do learn, because Coppola was the kind of director, and I tried to be too, that stood back and waited to see what you brought to the table. He didn’t say, do this, do that, like certain directors, certain old school directors. He was more and more up to date about really letting it come from the actor, and it was great working with him. And I tried to do that as a director as well, you know, let it come from the people.

AVC: You have such an incredible body of work. Are there other films you’re especially proud of that you feel like have not cultivated the reputation they deserve?

RD: Yeah. When I played Joseph Stalin, I got some tremendous feedback on that, but I even got negative feedback on The Apostle, if you can believe that. But I got a terrific letter from Marlon Brando. I showed him that and he really appreciated it. And I heard that Billy Graham appreciated it. So I got it from the religious and I got it from the secular, after that film on religion. But I enjoy directing too, somewhat. I mean, they say it’s very difficult to do, it’s so much work, but I found when it went well, acting and directing, at the end of the day, that was great. I wasn’t tired. So each project presents certain possibilities, certain challenges.

AVC: Having accomplished so much, is there anything that you never got to do or that you still want to do?

RD: Two films recently that will not get made, The Plowman, I was working on with Ed Harris. That’s not gonna get made, I don’t think. And there was one before that in Texas about a young lady and a mountain lion that killed her mother. It was very well written by a man and a woman, and we just couldn’t raise the money. It all comes down to money. And then people say, oh, Bobby Duvall, this and that, you say you can’t raise money? I’ll say it right now. I don’t care what my name is. It’s very, very difficult to raise the proper amount of money.