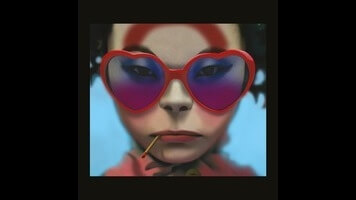

Gorillaz turn our national dystopia into more manic cartoon pop on Humanz

The key anecdote to know about the Gorillaz’s fifth record is this: Way back in 2015, when Damon Albarn was attempting to get his huge slate of collaborators on board with his vision of a hellish American dystopia, he asked them to imagine the country after something catastrophic had occurred, with the hypothetical example he plucked from a hat being Donald Trump winning the presidency. After that unthinkable nightmare became the churning content maw in which we live, Albarn and company did a sort of reverse retcon, scrubbing the record of explicit references to the new president. It was all a little too prescient, too on the nose; an album full of Trump-bashing would’ve been a part of our world, and not part of the cartoon universe that Albarn, illustrator Jamie Hewlett, and their rotating cast of collaborators have been conjuring over the past two decades in the grand transmedia Gorillaz experiment.

Still, that anecdote will haunt Humanz, and it’s easy to sort of groan about it: Oh good, another pop culture item to shoehorn into our greater post-Trump malaise, along with The Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, and every authoritarian post-apocalypse ever created. But then, Gorillaz have always been about America. Albarn and then-roommate Hewlett dreamed the whole concept up while watching MTV, challenging themselves to create something as distinctly artificial as the acts they saw parading across the screen during turn-of-the-millennium TRL. But what they ended up with was as much a comment on themselves as it was on Eminem, Marilyn Manson, and Orlando teen-pop. It’s right there in the band name, a reference to Noel Gallagher’s response when asked who, between Oasis and Blur, was The Beatles and who was the Rolling Stones: “We’re The Beatles and the Stones,” he said, “and they’re the fucking Monkees.”

With Gorillaz, Albarn leaned into that insult, creating something as disposable and TV-friendly as his other band had been accused of being. It’s a distinctly British attitude toward American culture—a sort of affectionate disdain—but the group’s elaborate cartoon fiction also served as an excuse for Albarn to explore the late-’90s globalist sampledelica of Cornershop, Jet Set Radio, and post-Odelay alt-rock, bringing in the rappers, riddims, and hypnotic loops that he was finding increasingly inspiring. The broader cartoon mythos started off as a handful of origin stories for the fictional quartet—hedonist rockstar Murdoc, pretty-boy singer 2-D, kawaii guitarist Noodle, and rapper amalgam Russel Hobbs. Since then, it’s blossomed into a broader transmedia monstrosity, its plot line spread out across myriad Twitter accounts, augmented reality games, interviews, web games, DVD extras, buildings, and a whole lot more. People have pieced it all together—you can read the full, mystifying saga on Reddit, or watch all of their videos in narrative chronological order—but it’s better understood as a sort of background mythology, like, say, the lore in a Dark Souls game. The fact that Noodle was briefly a cyborg or Russel was briefly a giant likely won’t factor into your actual enjoyment of Humanz.

And make no mistake: Despite its bleak real-world inspiration, Humanz very much wants to be enjoyed. This is, after all, the group that turned the environmental wasteland of Plastic Beach into a groovy, spy-movie island getaway, its broader fictions serving as an excuse to cycle through an endless string of guests. Humanz continues in this mold, flipping that album’s dreamy glo-fi mixtape (Snoop Dogg! Little Dragon!) into a relentlessly uptempo collection of nightclub anthems. A handful of the world’s best, most exciting rappers pop by, like Danny Brown, Popcaan, and Vince Staples, the last of whom opens the record with its functional thesis: “The sky is falling baby, drop that ass ’fore it crash.” Apart from a handful of interludes, Humanz never rests from this apocalyptic energy, mostly achieving Albarn’s stated goal of staying above 125 BPM by buzzing through ideas and cameos relentlessly. It can lead to whiplash, like when Kelela’s heavenly dance-floor siren routine flips to a more cacophonous turn by actual dance-floor siren Grace Jones, or the way the bellowing electro of “Carnival” is forced to give way to a Mavis Staples cameo and a Pusha T verse in the next track.

If all of that sounds like a bit much, well, that’s the problem with having too many guests on a record. Plastic Beach somehow bathed everyone in the same gauzy orange light, but the “party at the end of the world” conceit of Humanz necessitates more steam, more people, more characters, more. The tracks are all good—they are all “fun”—but there’s a manic intensity to it that doesn’t add up. We’re dancing away the pain, sure, but what are the stakes? It’s not Donald Trump, so it must be whatever’s going on in that greater Gorillaz lore, which—who’s the antagonist here, again? That loose relationship between the band’s music and their fiction is, on Humanz, finally a liability rather than an asset: For the first time, the music begs justification. It needs that Trump anecdote as much as it needs the 10-episode series Hewlett is reportedly hard at work animating.

All of this isn’t to say that the album is bad—Albarn’s dialed in, and the guests are meticulously curated—but rather that it seems dwarfed by its role as part of a larger concept, the music mostly valuable for its possible real-world applications in videos, on tours, as action figures and video games, and all of the other manufactured, disposable pop culture ephemera for which Gorillaz was designed. In a way, this is a fulfillment of their vision of themselves as a perfectly manufactured pop group: Humanz sounds like a soundtrack to what Hollywood types call a “property.” They’ve given in to the fictional machine.

That said, “humans” seems a strange theme for them, but it’s also their very humanness that gives the music its tension, its lifeblood. (The album’s best stretch is its last quarter, when Albarn’s high, reedy voice gets enough room to float out.) Gorillaz almost broke up after Plastic Beach because Albarn toured with real musicians front and center, their fictional counterparts relegated to between-set videos—much to Hewlett’s chagrin. On Humanz, the inverse is the problem: Albarn is largely invisible, his iPad beats and vast Rolodex filling the Day-Glo screen with high-polish hijinks. All the famous people and the cartoons are partying together, and it’s hard to know where the actual humans fit in. In that sense, it’s more like today’s America than ever.