Graduation is a work in progress for the adult students of Night School

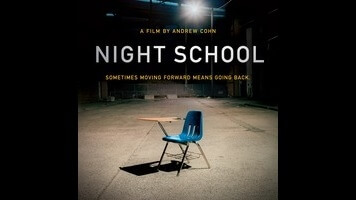

Here’s a tough reality of American life: Entire futures hinge on a thin scrap of paper, rolled up and handed out to teenagers. Stranger still, this particular scrap of paper, so crucial to so many career paths, can only be acquired at an age when the brain is almost comically resistant to thinking ahead. Well, at least that’s historically when you could get one. With Night School, documentarian Andrew Cohn (Medora) takes his camera behind the walls of the Excel Center in Indianapolis, where high school dropouts can enroll for free in an intensive adult-education program. If they pass all their final exams, these returning students earn a diploma—not a GED, but the real deal, basically indistinguishable from what they would have received if they had graduated the first time around. It’s like an accelerated version of high school, minus the dances and the extracurricular activities and the backdoor beer-buying schemes. It’s also something sadly rare in U.S. education: a second chance for those who have slipped through the cracks.

Shot in the all-access vérité style of one of Steve James’ slices of city life, Night School narrows its focus to three Excel Center hopefuls—all black, all balancing their studies with low-paying jobs. Greg Henson, who dropped out to sell drugs, is now a thirtysomething single father, determined to move past the missteps of his adolescence. Having left school as a teenage mother almost 40 years earlier, Melissa Lewis works at a secondhand store by day and grapples with algebra by night. And 26-year-old Shynika Jakes, who sleeps in her car when not crashing with friends, dreams of leaving her job at Arby’s to become a nurse. Beyond the occasionally maudlin lilt of the music, there’s no overt editorializing. But in the specifics of the stories being told, Cohn acknowledges the very real factors that drew his subjects out of the classroom—the allure of quick income, the burden of parenthood—even as all three openly admit that it was their mistake to drop out.

Night School builds toward a big exam at the end of the year, complete with a months-to-go countdown clock. It’s a familiar, foolproof dramatic structure; whether his subjects pass or fail, Cohn is guaranteed some climactic drama. A lot can happen over the course of a school year, even outside the social petri dish of actual high school: We see Melissa go on dates and fall in love, her excitement about the new romance contrasting with her anxiety about a class she might have to repeat, while Shynika becomes hesitantly involved with a social-action group striking for working wages in the fast food industry. Based on the scenes Cohn includes, it’s Greg who has the most eventful year; over just a few short months, his brother is shot, his young daughter is diagnosed with epilepsy, and an outstanding warrant threatens efforts to get his decade-old criminal record expunged. Persevering in the face of mounting obstacles, Greg becomes the movie’s inspirational center: a man forcefully setting his priorities straight and course-correcting toward the life he wants for his family.

When not shaping his footage into recognizable character arcs, Cohn steals fleeting glimpses inside the Excel Center itself, where faculty offer crash courses and break tough news on the students’ academic standing. When these teachers discuss a natural “purging,” wherein they essentially weed out those not serious about the program, one can’t help but wonder about the tougher, messier, more comprehensive movie Frederick Wiseman might make on this subject. (About the only impression of the learning process we get are close-ups of half-completed math equations; like most movies about school, fictional or otherwise, this one doesn’t risk boring its audience with many actual classroom scenes.) Night School takes the human-interest route instead, and while that doesn’t allow for the most complete vision of the program, it does put a touchingly human face on the movie’s opening statistic—as well as grant a sliver of hope for those 1.2 million American kids who abandon their education every year. We live in a culture that tends to give up for good on dropouts. Greg, Melissa, and Shynika are living proof that there’s no expiration date on “back to school.”