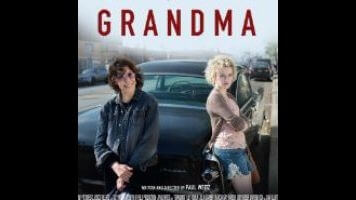

There’s a long tradition of films treating scrappy and lively older characters as a punchline, as if it’s inherently hilarious to see anyone above 65 swear, drink, fight, acknowledge sex with positivity or enthusiasm, or otherwise indicate they’re still alive below the neck. It’s taken the aging of the American population and the splintering of the film industry into specialty audiences to move cinema away from that trend. Old folks behaving badly are still a go-to stereotype, but they’re being offset by films like Paul Weitz’s Grandma, which touches on the sentiment and scorn of big, prestige-like family dramas like August: Osage County, but only in the lightest way possible. On paper, Grandma may sound like a drama, given how it revolves around lost loves, life lessons, and unwanted pregnancy. In practice, it finds the human side of the cussin’ granny character, and turns serious issues and sappy plot developments into a playful, only mildly melancholy romp.

A good chunk of the credit goes to Lily Tomlin, in her first starring film role since 1988’s Big Business. Tomlin plays aging poet and “unemployed academic” Elle Reid, a septuagenarian who’s snappish and so ruled by defensive pride that she’s alienated many of the people in her life, including her estranged daughter Judy (Marcia Gay Harden) and her current lover Olivia (Judy Greer). When her teenage granddaughter Sage (Julia Garner) turns up on her doorstep, looking for the money for an abortion she scheduled for the end of the day, Elle doesn’t have the cash, and has just cut up her credit cards to make yet another reckless statement about her independence and freedom. So the two of them go on a road trip, hitting up Elle’s old acquaintances for the money. Along the way, Tomlin makes it abundantly, entertainingly clear that Elle has never taken shit from anyone in her life. And she wants Sage to follow suit, especially when dealing with her sneering, immature baby daddy (Nat Wolff). But the same attitude that’s brought Elle freedom and some artistic respect has also left a trail of broken relationships behind her, and Grandma is more about revealing the limits and regrets of complete independence than about Sage’s situation, or even the evolving relationship between grandmother and granddaughter.

Writer-director Paul Weitz could have handled this material in a thousand ways, including the broad, loud, exclamation-point-filled comedy he brought to Little Fockers, or the wry, restrained grief he brought to About A Boy. But as with in 2012’s Being Flynn, he navigates awful-sounding material with a gentle, sympathetic touch, neither overplaying the violent-granny gags nor overselling the moments where the characters bond. Grandma is a rare chance for Weitz to work from an original script instead of adapting a book or sequelizing characters he didn’t originate, and while Grandma isn’t as elaborately worked and narratively complicated as Being Flynn, it does bring across Elle’s story in an innovative way, as her small-range trip around town becomes a journey into the past she doesn’t want to acknowledge. Instead of exposition about Elle’s 38-year relationship with her recently deceased partner, Violet, Weitz offers characters commenting on Elle’s tattoo of Violet’s name, or how Violet affected their lives. Elle doesn’t tell Sage who they’re putting the bite on next, or what hazards might come up in the interaction; her history unfolds through action, as she visits old acquaintances played by Elizabeth Peña, Orange Is The New Black’s Laverne Cox, and a shockingly facial-hair-light Sam Elliott.

Tomlin and Elliott’s scene together is worth the price of admission on its own; he’d steal the movie if it wasn’t so firmly in her hands. It’s a classroom-worthy study in narrative efficiency, bringing up information only as it’s needed, but making each progressive evolution of the emotion between them into a new revelation. Both characters underplay a core of fury and sorrow that manifests, as human emotion so often does, in ways that don’t immediately suggest anger or sadness. The sequence is emblematic of the rest of the film—both the restraint and talent that makes it work, and the brevity and jumpiness that limits it, keeping the story and the emotions small and moving events along with regrettable speed.

Grandma is a bottle episode of a movie, restrained not in space, but in time and incident. It only covers about eight hours in a family’s life. The abortion—treated gently and without judgment by the film—may stick with Sage, as Elle says, for the rest of her life. But the film isn’t designed for that kind of large-scale impact. It’s an artful, funny, endlessly surprising little acting and writing showcase that shows just how far it’s possible for writers to take tired, clichéd characters, by treating them as human beings and caring what goes on underneath the surface of the easy jokes.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.