Green screen, working with kids, rubber overalls—Willem Dafoe embraces it all

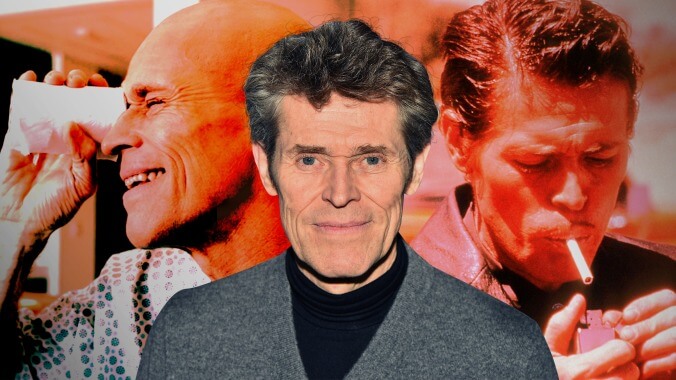

Image: Graphic: Allison Corr

The actor: With so many hard-working character actors out there plugging away for years and precious little recognition, why did The A.V. Club go back and do a second Random Roles interview with Willem Dafoe? Because he’s Willem Dafoe, that’s why.

But in all seriousness, Dafoe—who sat down for his first Random Roles interview with The A.V. Club in 2012—has had a hell of a decade. He’s been nominated for two Oscars, one for The Florida Project (2017) and one for At Eternity’s Gate (2018). He continued to develop his working relationship with directors Wes Anderson and Lars Von Trier, while forging new ones with up-and-coming directors like Florida Project’s Sean Baker and The Lighthouse’s Robert Eggers.

But while Dafoe is proud of his work in all of these films, My Hindu Friend (2015) might be the work from this decade that’s closest to his heart. In the film, Dafoe plays a character based on the film’s co-writer and director, Hector Babenco, the Brazilian filmmaker probably best known in the U.S. for his 1985 film Kiss Of The Spider Woman. Diego (Dafoe) is a director who’s dying of cancer and who forges a touching friendship with an Indian boy he meets on a cancer ward, a story that becomes even sadder when you realize that Babenco was himself dying of cancer during production, and died just a few months after the film’s release in Brazil. Nearly four years later, My Hindu Friend hit American theaters in late January, and is available for digital rental and purchase on YouTube, Amazon Prime, and Google Play.

My Hindu Friend (2015)— “Diego”

The A.V. Club: Working on this film must have been a very intense experience, both physically and emotionally.

Willem Dafoe: Sure, just in the fact that [I was playing] someone who’s been through a lot. And [Babenco] had a terrific stake in making this film because, although it is part fiction, it does draw a lot on autobiography. So the stakes were very high. And there is a period of the film where he’s quite sick, so I had to lose weight. I had to shave my head, and I spent a lot of time in the hospital. And of course, as we’re doing this, I was doing a lot of the same things that Hector went through, so they were very emotionally loaded. Plus, I’m shooting in his house, with his wife playing the love interest. So it was quite intense.

AVC: Were you acquainted with Hector before you started this project?

WD: I knew his movies very well. I met him—I remember this very well, cause he was a big person with a big personality, and charismatic—I remember meeting him at the Venice film festival when I was there with Last Temptation Of Christ. We hung out together, and we got along, and we kept in touch some. And then I lost track of him, not knowing exactly why. In retrospect, I know he was very sick for a while.

And when he came back, we talked about me doing a film called Foolish Heart. I think it was difficult to set up, because his health was uncertain, so he ended up doing it in Portuguese on a much more modest scale. So, we had tried to work together. And then I was in Sao Paolo with a theater piece of Robert Wilson’s. Hector knew I was there, so we met, and he showed me the script for Hindu Friend. He said, “I’d love for you to do this.” So it was quite direct. He said, “when can you do it?” And I told him when, and then we were off to the races.

AVC: I’m curious: You said Hector’s wife played your love interest in the film. What was that experience like? Did it help you get into character to be working with the real people?

WD: You’re dealing with so much. We were shooting at his house, so with everything we were doing—the ghosts of those original actions are still in the house, and you’re accessing them. While you are inventing some things, [the reality] is very present. And you have him always speaking in your ear, telling you what he went through. And you’re taking that on, trying to inhabit that state. When you’re confronting death and when you’re spending time in the hospital and you’re around hospital culture all the time, you can’t help but personalize that. It’s so easy to imagine yourself in that position.

Streets Of Fire (1984)— “Raven Shaddock”

AVC: You wear a pair of rubber rubber overalls in this movie…

WD: Designed by Giorgio Armani, yup.

AVC: It just seems very uncomfortable inside a pair of rubber overalls.

WD: They looked good. I’m an actor, so if I’m looking good, I’m feeling good. What can I say?

That was pretty much the first studio film I ever made. Walter Hill said when he wrote the script, he made a list of all the things he loved to see when he was young going to the movies, and he tried to do all those things in the story. And he basically did. So it was a film made with a lot of love,.

I think it was ahead of its time, and it’s now being appreciated in retrospect. And when I run into people who are Streets Of Fire fans—man, they’re hardcore. So it’s a movie that lives well in my memory. It’s fun when you’re playing the head of a motorcycle gang and your entourage is 50 guys on Harley-Davidsons. That’s a pretty extreme—and pretty fun!—fantasy experience.

AVC: Your first studio movie, and you have all these guys in an alley behind you. That’s pretty cool.

WD: I had a good head of hair, too.

AVC: You mentioned that Walter Hill had this list—did you connect with that? Since you guys are from different generations.

WD: It is a different generation. But it was more that he’s a great cinephile. He was steeped in cinema culture, and particularly at that point, I was more of a guy from the theater. My knowledge of cinema was very poor. So it’s only in retrospect that I appreciate some of the references, and some of the stuff that was consciously, or maybe even unconsciously, quoting from classic films.

The Florida Project (2017)—“Bobby”

AVC: Did you film this one after you filmed My Hindu Friend?

WD: I filmed it after. Hector died in 2016, and we finished the year before. That’s long before The Florida Project.

AVC: So did that experience give you a precedent for working with non-professional actors? There are quite a few of those in this movie.

WD: It depends on what kind of film you’re making. Sometimes it’s very enjoyable [to work with non-professionals]. If they’re from the world, and they’re doing things that they know how to do, then it’s not a problem. With performers that aren’t usually actors—yes, they have limitations. They aren’t skilled at repeating things, and sometimes they can’t exactly drive a scene. They may need special kind of environment on the set to perform well.

But they have such a clean sense of play. And there’s this realism to having no ego or identity as an actor, so they can be very free. And if they’re inhabiting something that’s a fantasy for them, particularly with the children, they can be very pure in that performing. So I don’t mind [working with non-professionals] at all.

And on any movie, since there’s not a uniform training for actors or a uniform career track for acting in movies in the States, you’re always dealing with people with a wide range of experience. Some people are very trained, and some people are just naturals who are really good in front of the camera. Some are experienced theater actors, some are models… it’s a mixed bag. So every time you do a movie, you have to deal with what’s there.

And I kind of enjoy that, because you’ll always find new ways to perform and new ways to approach things. That’s the way to keep your performing alive, rather than have your process harden into a very strong sense of rules or conditions. Because those are the things that I think really weigh down an actor, when they start to create “I don’t do that”s or “I don’t like that”s. You gotta be flexible. And I think sometimes working with a wide range of people and a wide range of experience really helps you with a certain kind of flexibility and tolerance. And curiosity.

AVC: Well, all those words apply to your performance in that film. In your interactions with Brooklynn Prince and all the other kids—they’ll ride by on their bikes, and you’re exasperated, and it just feels like a real moment, you know?

WD: Sean Baker is very good at creating an atmosphere, to make the kids very relaxed. And also we were shooting in a real place, so the people there really taught us how to behave in that world. I wasn’t trying to be an actor as much as I was trying to be a good manager of that hotel, basically.

Spider-Man (2002)— “Norman Osborn/Green Goblin”

AVC: The superhero film culture was different in 2002. It wasn’t as all-encompassing as it is now.

WD: It was. That was one of the things that was really fun about it. For Sam Raimi, it was a personal film.

Also, some of the effects weren’t as developed then, even as much as they were in subsequent Spider-Man movies. So I enjoyed it, because there was a lot of kind of classical wire work and flying around. People were trying to figure it out, you know? And there’s a passion that comes from that kind of problem solving. So that was really a fun experience. The cast was good; it was cast very well, and Sam was really fun to work with. I think it’s a good movie. It effortlessly goes back and forth between drama and comedy, you know? It doesn’t point to itself too much. It’s not kitsch, but it has a good sense of humor about itself.

Aquaman (2018)—“Vulko”

AVC: You mentioned that the technology was changing movie over movie; was there anything in particular that changed for you between movies? As in, you did wire work for one film, and then in the sequel it was CGI?

WD: Not specifically. The CGI gets more sophisticated every time. On the first Spider-Man, it was strictly practical. But by the time I got to Aquaman, while there was wire work on that, there were these new innovations. Now you can basically key in on the monitor and see the mock-ups for the sets, so rather than just the straight green screen, you can go to the monitors [while you’re shooting] and see what it’s going to look like. We didn’t have that kind of sophistication with Spider-Man—at least, I wasn’t privy to it.

AVC: I always wonder that aspect of it. I did an interview with Samuel L. Jackson where we talked about The Phantom Menace, and he said you really have to act, because you’re in front of a green screen looking at a tennis ball. He said you really have to put yourself in the moment.

WD: Yup. I think with green screen, if you embrace it rather than complaining about it, it can be a lot of fun. Because it’s up to you. It’s all in you. It’s all in your imagination, because you have to create these things in your head.

The Lighthouse (2019)—“Thomas Wake”

AVC: Your dialogue in this film is very stylized. Was it more difficult to deliver that style of dialogue versus something more naturalistic, or is that where your theater training kicks in?

WD: It’s where the theater training kicks in, and I loved it. It’s very evocative. You do have to practice [that style of dialogue]. It’s got a music and a rhythm that is part of understanding the sense of it. The big trick, besides finding the music and the rhythm, is that it still has to feel like natural dialogue. Because the style of the movie—although it’s got elevated language, and even though some of the behavior is quite extreme, it’s a naturalistic movie.

I really enjoyed it, because you can be far more articulate when the language is so specific and when the images are so juicy. So, emotionally, it plays on you much more than more prosaic or more conversational dialogue. That was one of the great pleasures of working on this film. And I think Robert Eggers and his brother both have a great facility for writing that type of dialogue. I mean, it’s quite amazing.

AVC: How long were you out in this remote location? Were you being taken on a boat into the set every day?

WD: No, no, it was a peninsula. It’s made to look like an island, but there was this little spit of rocky peninsula that we built the lighthouse on. And I was staying in the fisherman’s cottage, which was quite close to the set. So it wasn’t a big deal getting to the set every day. We did, I think, 35 days of shooting—there was some studio work in Halifax, but the majority of it was on location.

AVC: Staying in the fisherman’s cottage must have been helpful for immersive purposes.

WD: Well, you wake up every morning and the first thing you do is you check the weather. You look out and you start the fire to get the place warm. It definitely puts you in the state of mind of someone that’s living in nature and has an intimate relationship with the weather, which certainly is a huge character in the movie.

AVC: You mentioned just before that you, you know, embrace green screen—

WD: I try to embrace everything. [Laughs.] If I’m in a movie with green screen, I’m gonna love it. That’s the nature of being a performer: You see what’s there, and you use it the best you can. That’s all.

AVC: I was just wondering if it was helpful to be in an immersive environment, or if it was not really necessary. You know what I mean?

WD: No, of course it’s helpful. It’s fun. Sometimes you’ll have a director that really creates a specific world—whether it’s David Lynch, or whether it’s Wes Anderson, or whether it’s Robert Eggers—and when you enter that world, you’ll know exactly what has to happen. All your energy doesn’t go into sussing it out and figuring out strategy. All your energy goes into being present, and the actions that you do. And what you have to do becomes very, very clear.

The heart and pleasure [of performing] is in being present in a very full way, receiving what’s there, and letting it have the capacity to surprise you. If you’re trying too hard to figure out the world, I don’t think you’re as available, because you’re shepherding the world too much, you know?

Wild At Heart (1990)— “Bobby Peru”

AVC: Bobby Peru scared me so bad. It’s a very unnerving performance. What was it like shooting this role, with the teeth and everything?

WD: It was beautiful. It was beautifully written, and David Lynch is fun to be around, and Laura [Dern] and Nic [Cage] were fun to perform with. Lynch creates a very specific world, and I had great externals there as far as a real performer’s mask. As you said, I had the teeth, and I had a very specific look and way of speaking. The language was very beautiful.

He’s bad without apology, which is always nice because there’s always a temptation to kind of tip your hand and, you know, justify why a character is bad, or find the psychology. There’s no psychology there. That guy, you know exactly what he wants. And operates on a level that’s almost superhuman, because his appetites are not colored by any social considerations. He’s an interesting character because he’s such a force of nature. And then, of course, you’ve got the scene where he seduces Laura Dern. When she submits to him, he basically turns it into a joke, exposing the fact that he’s not really interested in the seduction, just the power game.

AVC: You called Bobby Peru a force of nature… from what I know about Lynch’s process, it’s very intuitive. So I imagine that’s all of a piece for him?

WD: Yeah. And, as you said before, fitting in with what you were talking about, he makes you a very complete world. It’s quite clear. That was a long time ago. I’m sure he’s changed a lot. But at that point—for example, with my costume, there was no discussion. It was, “here’s your costume.” It was practically handed to me on a on a hanger. He was very clear about [what he wanted], yeah.

The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004)—“Klaus Daimler”

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009)—“Rat”

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)—“Jopling”

The French Dispatch (2020)

AVC: Speaking of directors who create a specific world, you’ve worked with Wes Anderson several times now.

WD: I’m in the new one as well.

AVC: What keeps you coming back?

WD: I like his movies. He gives me fun things to do, and it’s always fun to work with him.

AVC: What kind of atmosphere is there on set? Anderson’s got this reputation for being particular, I think because of the precise composition of his films.

WD: That’s true. But he also makes it a good life adventure. It’s a very social environment, because he tends to get very strong casts to hang out together. Specifically with The Grand Budapest Hotel, we were all staying at the same hotel every night in the spirit of the Grand Budapest Hotel. We’d have dinner together, people would come and go.

He makes a world. He makes a world within the world. And I think actors really respond to that. It creates a camaraderie where everybody is patient, and everybody works very hard. Yes, he’s demanding, but everybody’s there for that world and they’re there for Wes. So it’s very clear. So yeah, there’s a camaraderie that he creates. He’s demanding, but he’s a very sweet person who’s very committed to what he’s doing. So everybody respects that by being patient with his very specific instructions, and sometimes going for very many takes.

AVC: What’s very many? Dozens?

WD: Oh yeah. Well, I’m used to working on movies where you get maybe two takes, so—you know.

AVC: Oh, wow. No pressure there, huh?

WD: That’s actually not a bad way to work sometimes.

AVC: Why?

WD: Because you don’t wait. You put it out there. And I’m used to that, because in the theater, I was used to rehearsal that afternoon, and trying new stuff most every night. It’s always nice to have that little sense of flying by the seat of your pants.

Murder On The Orient Express (2017)—“Gerhard Hardman”

AVC: How about another big ensemble piece, Kenneth Branagh’s Murder On The Orient Express? What was that experience like? Did it have that communal aspect you were talking about?

WD: It had a little bit of that. They were very, very, very, very different experiences, but similar in the respect that everybody was there full-time. It’s an ensemble, so nobody has to do any super heavy lifting. [Branagh’s] got the heavy lifting. But everybody has to be around all the time, because they’re part of the world. So we have these great actors that are used to headlining movies basically being part of the ensemble. But, I think largely because a lot of them are also English actors who are used to the theater, they’re also used to doing all kinds and sizes of roles. They’re used to sitting around. [Laughs.] It was beautiful.

You’d have to be around, everybody would have to be around, because they didn’t make any special [accommodations]. They didn’t shoot people out too much. Kenneth would a little bit, so he could direct. Sometimes he’d shoot his side and then we’d shoot complementary shots for him, so he could be in it and watch. But generally speaking, everybody was there every day, and it was kind of sweet. Everybody would come in in the morning, and there was a real good feeling to it. You’d get on that train, and you’d start to work. And yeah, there was a lot of hanging out, but everybody enjoyed it because also you had a lot of beautiful, experienced theater people. There was always a good humor, and a lot of swapped stories.

At Eternity’s Gate (2018)—“Vincent Van Gogh”

AVC: Playing Vincent Van Gogh, the character was much younger than you were when you were playing the role. Did that factor into your characterization at all?

WD: I guess nobody gave you the bulletin, huh?

AVC: I guess not—what do you mean?

WD: Ah, you didn’t get the memo! I think that thing about age is bullshit. Yeah, Van Gogh was 37 years old when he died, but he was not a young man, first of all. Mortality in the time he died was different, their 40 was our 75.

AVC: You know, that’s a great point.

WD: This was not a young man. And he had a lot of physical problems. He was an alcoholic, and he was pretty beat up. So I may be older than him by numbers, but I never gave age a single thought. Plus, you have to think about this: He was a man that really lived life. A 37-year-old man now is not having the same kind of experience.

I don’t know. I never gave a thought, and I found it piddly and beside the point when people would discuss that issue. Watch the movie—nobody should be thinking about age. I think it’s a beautiful movie. And if you’re thinking about that, you’re a moron, what can I say? Not you personally, of course.

AVC: [Laughs.] I know, I know. I know what you mean.

WD: Whoever even started that idea lacks imagination.

AVC: So what were you thinking of, then? What was your focus for the character?

WD: Primarily, it’s a movie about painting. And his letters. His letters are very intimate, and very beautiful. We used his word, I speak some of his words in the film. That was a lot. I was in the place where he was, and I was looking at the things he was looking at. But above all, I’d say I concentrated on the painting. It was a wonderful experience, because I was very full and engaged.