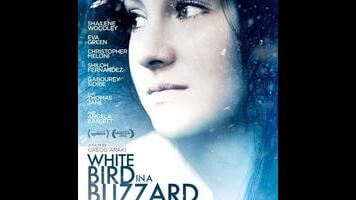

Gregg Araki chases respectability (again) with White Bird In A Blizzard

Back in the early ’90s, few people would have predicted Gregg Araki would still have a significant filmmaking career 20 years later. Early efforts like 1992’s The Living End and 1993’s Totally F***ed Up were pretty uneven, but that’s not the reason—even back then, Araki’s talent was evident. It’s more that he was someone who’d title a movie Totally F***ed Up. Outrageousness and shock value were his stock-in-trade, and while that kind of thing can be liberating, it can rarely be sustained; the well eventually ran dry even for the mighty John Waters, who hasn’t made a feature in the past 10 years.

Araki apparently figured that out. Right about the time that his shtick started to seem tired, he switched gears, adapting Scott Heim’s novel Mysterious Skin into a film that, while often disturbing, was uncharacteristically restrained by Araki’s standards, featuring a powerful, dramatic performance by Joseph Gordon-Levitt. It’s widely considered to be his best work, and kicked off a second creative wind that’s included both goofy stoner comedy (Smiley Face) and an inspired return to sheer lunacy (Kaboom). Neither of those films drew a sizable audience, though, and so it’s no surprise that Araki’s latest film, White Bird In A Blizzard, is another literary adaptation, gunning for respectability. It’s the most mainstream and accessible picture he’s ever made, but this time his pendulum swung a bit too far in that direction.

Set in the late ’80s (which allows Araki to plaster the soundtrack with his favorite indie rock from that era), White Bird stars Shailene Woodley as Kat, a formerly overweight girl who’s just discovering her sexuality after slimming down. Puberty belatedly reaching full strength happens to coincide with the mysterious disappearance of Kat’s mother (Eva Green), a voluptuous vamp prone to heavy flirtation with any man who crosses her field of vision, excepting Kat’s highly irritable father (Christopher Meloni). Sessions with a therapist (Angela Bassett), first romance with the hunky next-door neighbor (Shiloh Fernandez), and a creepy dalliance with the detective (Thomas Jane) investigating Mom’s vanishing act distract Kat from the truth of what’s going on around her, which she stubbornly refuses to acknowledge even when it’s obvious.

Part of the problem with White Bird In A Blizzard is that the film thinks its audience is just as dense as Kat. Playing keep-away with the revelation of what happened to Kat’s mother (and related activity) is pointless, as most viewers will tumble toward it almost immediately, and keeping us in the dark largely negates what the film is trying to say about Kat’s willful obliviousness. The emphasis should have been squarely on her, and it’s Woodley’s typically forthright, heartfelt performance that keeps White Bird aloft. She’s not concerned with remaining likable at all times, which makes her a good match for a director like Araki; Kat’s occasional brattiness and self-destructive impulses are consistently more compelling than are the flashbacks to Mom doing her va-va-voom routine (Green, overripe, is acting in a different kind of Araki movie) or Meloni’s unconvincing histrionics. Extremely literary voice-over narration suggests that the novel, written by Laura Kasischke, relies largely on Kat’s internal monologue, making it a tricky source for adaptation. Using only tiny snippets of it, the movie sometimes seems like it’s just an excuse for Araki to restore his serious-filmmaker credibility while spinning some choice Cure and Joy Division tracks.