Gus Van Sant’s uneven career took off with the half-great My Own Private Idaho

Some filmmakers are remarkably consistent, hitting roughly the same section of the dartboard every time, whether it’s right near the bullseye or way out by the perimeter. Others, like Gus Van Sant, are more erratic, equally likely to produce a triumph or a disaster. For every Drugstore Cowboy and To Die For in Van Sant’s filmography, there’s an Even Cowgirls Get The Blues and a Restless; when he unexpectedly hit mainstream pay dirt with Good Will Hunting (as a director for hire), he immediately squandered that capital by remaking Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho with Vince Vaughn and Anne Heche. Even when signs look good, things can turn ugly—his most recent film, The Sea Of Trees, was selected to play in Competition at Cannes, but wound up receiving such brutal reviews there that it may have singlehandedly ended the McConaissance.

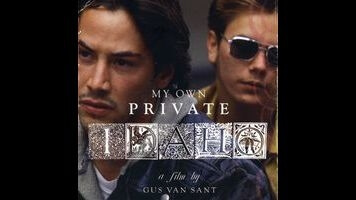

Most people would place My Own Private Idaho (1991), Van Sant’s third feature, in the triumph category. (It’s receiving a Blu-ray upgrade from Criterion this week, a decade after it first added it to its collection.) Both Mala Noche and Drugstore Cowboy had been widely admired, but this was the movie that really put Van Sant on the map, confirming him as a major talent with a singular, confident voice. The seeds of his subsequent wild variability, however, were originally sown here. In truth, My Own Private Idaho is two separate films inelegantly stitched together, only one of which is first-rate. The other stems from the same sort of harebrained idea that led to a laughable shot of Norman Bates frantically jerking off.

First, the terrific movie: a tender story of unrequited love involving two Portland street hustlers, played by River Phoenix (two years before his death at age 23) and Keanu Reeves. Mike (Phoenix), the more sensitive of the two, suffers from narcoleptic cataplexy, which means that he regularly keels over at moments of high stress. His best friend, Scott (Reeves), takes this in stride—they sometimes service the same clients, with Scott having to drag an unconscious Mike away—and the two share a unusually close bond, eventually traveling together to Idaho and then Italy in search of Mike’s mom, with whom he lost contact years earlier. But their relationship is complicated by Mike’s intense desire for Scott, who’s fundamentally straight and only has sex with men for money. When Scott falls in love with a young Italian woman (Chiara Caselli), their joint odyssey abruptly ends, leaving Mike as adrift as he’s ever been.

Now that Joaquin Phoenix is considered one of the greatest actors of his generation, it can be hard to remember that he started out in his brother’s considerable shadow. River won several Best Actor prizes for this performance (Venice Film Festival, National Society Of Film Critics), and he’s achingly vulnerable; a campfire scene in which Mike tells Scott how much he wants to kiss him is almost too painful to watch. But Reeves, too, does impressive work, at a time when he was primarily known for playing amiable goofballs in Parenthood and the Bill & Ted movies. Both actors took a significant public-image risk by accepting these roles back then (though Van Sant fashions the sex scenes as arty montages of still photos), and neither makes any attempt to distance himself from the sordid milieu or the raw emotions. They put their trust in their director, who rewards it by creating a visually arresting movie around them while always keeping them front and center. From a marvelously witty sequence in which hustlers dish with each other from the covers of porno mags to the disturbing dream of a house falling from the sky onto a lonesome highway, My Own Private Idaho features some of Van Sant’s most striking, memorable images.

The thing is, though, the Mike-searches-for-his-mom narrative is decidedly on the skimpy side. Van Sant therefore decided to combine it with another, unrelated idea he’d been kicking around: a modern-day take on Shakespeare’s Henry IV (both parts) and Henry V. Scott is revealed, improbably, to be the son of Portland’s mayor; he’s just dicking around with prostitution until he comes into a massive inheritance, at which point he’ll join high society and his youthful indiscretions will presumably be forgotten. (Uh-huh.) There’s also a Falstaff figure, named Bob (played by William Richert, himself the director of such films as Winter Kills and A Night In The Life Of Jimmy Reardon), who shows up early in the film for the sole purpose of being spurned by Scott near the end of it. The dialogue for these scenes is straight out of Shakespeare (rewritten in contemporary English), and My Own Private Idaho grinds to a halt every time it abandons its original story in order to indulge in some lightly reheated Bard. Van Sant never found a coherent way to combine the two ideas, which makes Idaho’s Henry-derived material come across as a gimmicky distraction from something heartbreakingly sincere. It doesn’t ruin the movie, but it was the first indication that this gifted filmmaker had some clunkers rolling around among the inspiration. Confirmation soon followed.