Hanya Yanagihara’s latest epic, To Paradise, is a muddled slog

At 700-plus humorless pages, the third novel from the author of A Little Life asks too much of its readers

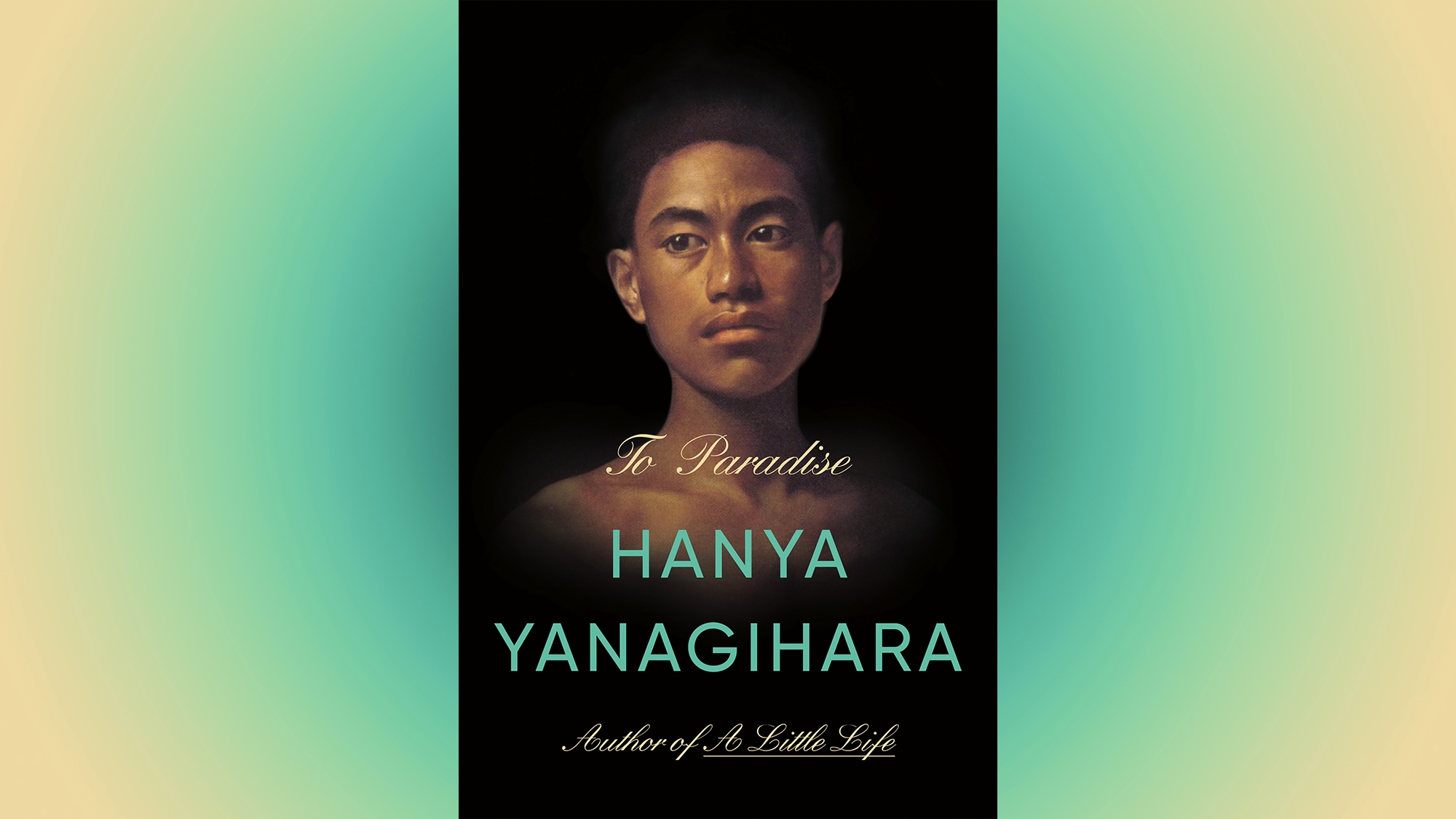

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Hanya Yanagihara’s third novel, To Paradise, asks a lot of its readers. First, that they hang in for 700-plus pages. Second, that they repeatedly leave behind a full cast of characters without learning their fates. Third, that they keep straight roughly a dozen different people named David or Charles. And fourth, that they accept both the logic of a dystopian future and an alternate history of the United States that sometimes contradicts much of what they might understand about human psychology.

In exchange, they will be rewarded with glimpses of tenderness, the familiar yearning for a paradise that doesn’t exist, and sumptuous descriptions of rich people’s dinner parties. The question is, is that enough?

The book’s through-line is a townhouse located in New York City’s Washington Square. Told in three sections, To Paradise checks in with the inhabitants every hundred years. Section one, set in 1893, follows a young banking heir named David Bingham, who must choose between his dull, nouveau riche suitor, Charles Griffith, and a con man, Edward, who has beguiled him with dreams of the West. The Northeast is its own country called the Free States, where gay people may marry. The West is a separate territory. The South is called the Colonies and has lost the war “but seceded anyway, sinking further into poverty and degradation by the year.”

Despite the name, freedom in the Free States extends only so far. Marriages are arranged, even between men, to accumulate property. Who is permitted to marry and why is central to the book, maybe because it provides a useful, if not subtle, metaphor about the intrusion of the state into the personal lives of its inhabitants. Meanwhile, hatred of Black people is total, and seems to exist in a vacuum, enduring even in a culture where homophobia and xenophobia of (white) immigrant children have been eradicated.

These rules read as strange, not because anti-Blackness in any version of America is difficult to imagine, but because it is so neatly siloed. Possibly Yanagihara has built her world this way to highlight one of our most pernicious issues. But how citizens of the 1800s have arrived at acceptance of nearly everyone else is one distraction among many that make it difficult to grasp what the novel is getting at.

Book two jumps ahead one hundred years to 1993. You might expect a link to section one. But there is no mention of the characters or how the experiment of the Free States concluded. We are deposited in an AIDS-ravaged New York that resembles our own world. David Bingham, this time descended from Hawaiian royalty, attends a farewell party for a dying friend at the Washington Square townhouse, which now belongs to David’s boyfriend, Charles Griffith. The plot takes us back to David’s upbringing in Hawaii, and once again cuts off before the conclusion of the narrative.

By book three, the New York of 2093 has plunged into totalitarianism in the face of catastrophic climate change and endless, rolling pandemics. Washington Square Park has become a tent city and is later razed altogether. Tragically, the townhouse has been divvied up into eight apartments. Charles Griffith, a monstrous doctor in the mold of Mengele, tries to save humanity by instituting death camps, while wrangling with his rebellious son, David Bingham. One of the pandemics has killed a generation of children and so, to promote procreation, marriage between men and women has been made compulsory.

Read most generously, the three books stand alone as proposed multiverses, rather than linear episodes. In part two, David muses, “Suppose the earth were to shift in space, only an inch or two but enough to redraw their world, their country, their city, themselves, entirely? What if Manhattan was a flooded island of rivers and canals, and people traveled in wooden longboats, and you yanked nets of oysters from the cloudy waters beneath your house, which was held aloft on stilts?” He goes on imagining alternate Manhattans. A metropolis “rendered entirely in frost,” a Manhattan that looks the same but with no one dead of AIDS.

This would appear to be the key to understanding the novel. But scattered allusions to the storied Bingham family undo this interpretation. And in book three we get a limp explanation of how two of the sections relate: Book one is a story told by a Washington Square storyteller in 2093, who is disappeared by the government before he can finish it.

Yanagihara’s first novel, The People In The Trees, focuses on the abuses of colonialism, culminating in multiple horrific rapes of children. Her second book, A Little Life, grandly exploits the suffering of gay men, leaning once again on childhood sexual abuse. But while those books are in bad taste, voyeuristic, overwrought, and repellently titillating, they are also juicy and engrossing. This book is just boring.

Women exist mostly as sidekicks and surrogates. Life’s dramas—its marriage plots and childrearing and apocalypse rescues—are left to the men, the various reincarnated Davids and Charleses. But these reincarnations are not one-for-one. It never becomes clear whether the characters that share names are meant to be distant relatives or the same person. If all the Davids are the David, if all the Charleses are the Charles.

You might feel compelled to make a chart of how various traits and relationships track between characters with repeating names. Go ahead and get out the bulletin board and red string—it won’t help. David and Charles sometimes have a happy romantic relationship, but sometimes not. Or a Charles is a Charlie’s grandfather. Or a Charles is a David’s father. Or a David is a David’s father. As section-three Charlie remarks, in perhaps the book’s only funny moment, “That’s a lot of Davids.”

David is all of us, the book seems to say, and Goliath is the government, infectious disease, climate change, the colonizers, the jackboots at the door, the bulldozer of history that will, in time, plow us under like a Washington Square shantytown in the year 2093. All the forces that can, and have, destroyed paradise.

But ultimately, the gimmick is too silly, too diffuse, for the book to succeed. The loving relationship between this Charles and that David, or that David and this other David, is subsumed by general confusion. The luxe meals eaten at the townhouse dining table—the delicate shards chiseled from a chocolate mountain, the “ginger-wine syllabub,” whatever that might be—don’t redeem it. Each section ends with the refrain “to paradise,” an enormously corny conceit that undermines otherwise moving scenes. It’s a shame because the idea feels true, the yearning for some imaginary place, some antediluvian world. What’s almost lost in all the noise is that none of the characters ever make it there.

Author photo: Sam Levy