Nowadays, just about every major public scandal gets turned into a feature-length documentary. The challenge for the filmmaker—assuming a quick cash-grab isn’t the aim—is to find an angle on the material that hasn’t already been wrung dry by the daily news media. Ideally, the movie will take its time, dig deeper than previous deadline-driven journalists could manage, and finally emerge when the scandal is in danger of being forgotten, the public and the media alike having moved on to fresh meat.

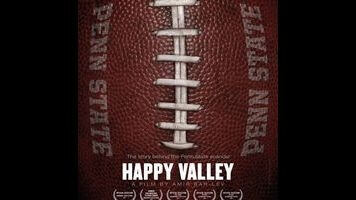

That’s not so much the case with Happy Valley, Amir Bar-Lev’s account of the sexual-abuse charges that rocked Penn State three years ago, landing retired assistant coach Jerry Sandusky in prison and resulting in the dismissal of longtime head football coach Joe Paterno (who died of cancer two months later). As its title suggests, the film aspires to be a portrait of the surrounding community rather than an exposé—a good thing, since it has no new information to offer regarding the case, and doesn’t even do a terribly coherent job of organizing the details for the benefit of some hypothetical ignorant viewer. But Happy Valley’s thesis, stated bluntly multiple times, is an overly familiar one: that Americans worship football too blindly, ignoring aspects of the culture surrounding the game that are clearly destructive. A documentary about such obsession as it applies to high-school football, Go Tigers!, came out way back in 2001, and the same idea pervades the book that inspired Friday Night Lights (film and TV show). That’s not to say that it isn’t relevant to the Penn State scandal, but there’s a big difference between relevant and revelatory.

Given the right subject, Bar-Lev can definitely accomplish the latter. His 2007 film My Kid Could Paint That, about the controversy surrounding a 4-year-old abstract artist, ranks among the finest documentaries of the past decade, getting to the heart of genuinely complex ideas about our collective hunger for narrative. Here, however, all he really manages to do is get a few locals to hang themselves with their own rah-rah rope. It’s hard not to cringe when a self-involved Penn State student complains to the camera that all the attention being paid to Sandusky’s victims is killing school spirit, or when people trying to have their photo taken beside a statue of Paterno (since torn down) heap abuse on a protestor who gets in their way (though, to be fair, the protestor yells things like “pedophile enabler!” at them).

Mortifying though such moments are, Bar-Lev ultimately fails to make the more damning case that such willful indifference was what allowed Sandusky to prey freely on the region’s kids. It’s a touch glib to repeatedly raise the question of why Paterno didn’t contact the police after hearing about a specific incident, then imply that the answer can be found in these ordinary citizens’ admittedly selfish desire for things to go back to normal. Happy Valley’s interviews with figures directly related to the case—Paterno’s widow and sons; Sandusky’s adopted stepson, who suddenly declared himself another of Sandusky’s victims toward the end of the trial, after having previously denied having been abused—shed no light on the subject whatsoever, coming across like an obligatory waste of time. The most likely culprit, so far as Paterno and other Penn State officials are concerned, is just the natural human tendency to ignore things that one doesn’t want to believe—especially when those things, should they prove to be true, will reflect poorly upon your judgment. But that simple thesis wouldn’t support an entire movie.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)