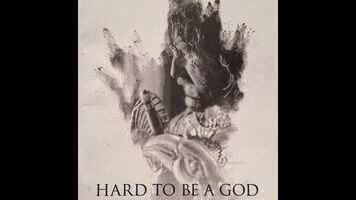

Hard To Be A God will take you to a world of shit

The plot of Hard To Be A God—the late Aleksei German’s decades-in-the-making medieval sci-fi flick—is relatively straightforward, but it’s often difficult to follow, because it’s buried under all of the mud, muck, smoke, decay, and shit that German crams into every frame. To put it another way: If Hard To Be A God isn’t the filthiest, most fetid-looking movie ever made, it’s certainly in the top three. Everyone seems to be continually kicking each other, spitting on each other, or beating each other—and if they’re not, it’s because they’re busy picking things out of the mud, poking bare and dirty asses with spears, or smelling what they just wiped off their boots. It is grotesque and deranged and Hieronymus Bosch-like, and damn if it isn’t a bona fide vision—but of what, exactly?

German—pronounced with a hard G—is probably the most important Russian filmmaker to remain more or less completely unknown in the United States, and Hard To Be A God is the movie he spent almost his entire career trying to get made and the last decade of his life trying to finish. It’s an adaptation of a 1964 novel by the Strugatsky brothers, Arkady and Boris, heavyweights of Soviet sci-fi. The Strugatskys wrote Roadside Picnic, which Andrei Tarkovsky adapted as Stalker, and Definitely Maybe, which Aleksandr Sokurov made into Days Of Eclipse. In short, they wrote the kinds of novels that make Russian filmmakers create the sort of drizzly, overcast long-take inquires into the cosmic unknown that are more or less unique to Russian cinema.

In simplest terms—the kind that don’t really account for all that stuff going on in front of the camera—Hard To Be A God is about a scientist, part of a team sent years ago to a distant planet to live among its human-like natives. The planet resembles feudal Europe, only somehow much worse; the observation team was sent there in the hope that they could witness a cultural renaissance firsthand, except that said renaissance never ended up happening. Now, they just live among the locals—he (Leonid Yarmolnik) as Don Rumata, a nobleman in the brutal, decrepit Kingdom Of Arkanar—and meet up once a year to swap stories, get (literally) shit-faced drunk, and tear up the empty medieval countryside in their tank. Forbidden from interfering with the planet’s cultural or technological development, they must instead content themselves with watching as its inhabitants repeatedly fail to pull themselves out of a dark age. Hence the title, Hard To Be A God.

“This isn’t Earth,” declares the narrator at the very beginning of the movie. Of course, it sort of is Earth, or maybe just one country in particular—a country with a weakness for political strongmen, a storied history of imprisoning intellectuals and artists, and a tendency to explain away cultural repression through the rhetoric of populism. Perhaps it’s because these kinds of things tend to be cyclical and predictable that Hard To Be A God, a project begun in the mid-1960s as a commentary on Stalinism and filmed in early- to mid-2000s, looks, at least in part, like an attack on Putin-era Russia. It sure as hell wasn’t intended that way, but that’s how it plays. Go figure.

Hard To Be A God follows the man known as Don Rumata as he grows increasingly unhinged, his neutrality—the thing that makes him a god-in-disguise—eroded by years of watching free-thinkers get strung up in town squares and by his struggles with Don Reba (Aleksandr Chutko), a rival nobleman with his eye on the throne of Arkanar and a personal secret police tasked with suppressing science, art, and literacy. What Hard To Be A God resembles most—other than German’s previous film, the Stalinist nightmare Khrustalyov, My Car!—is Orson Welles’ similarly muddy Shakespeare pastiche Chimes At Midnight. It’s shot in black and white, mostly handheld, with face- and body-distorting wide-angle lenses. It sounds a bit like Welles, too; like a lot of Russian filmmakers of his generation, German tended to post-sync all of the sound in his films, giving Hard To Be A God the clear, claustrophobic quality of a radio play, straight-into-the-mic voices rumbling over a soundscape of scraping, clanging metal, and Foley rain.

Comparisons with Welles tend to dog German’s later work, in part because of his tendency to run into financial troubles and work piecemeal (Khrustalyov took seven years to film; Hard To Be A God took six, and was still in post-production when German died in 2013, aged 74), and because of their similar visual styles and shared taste for raucousness and movement. Even when one isn’t entirely sure what’s going on in Hard To Be A God, there’s at least something to look at, be it a mass procession of soldiers in Don Quixote helmets or a man swinging a flamberge sword over his head like a helicopter blade. And, in the end, what leaves the strongest impression is what German crams into the frame; regardless of its themes of political repression and its undertones of religious inquiry, Hard To Be A God is first and foremost a vision of human misery, brutality, and ignorance. Except, of course, none of these people are human and this isn’t Earth. It just looks like it.