Harlots’ candy-colored shell can’t hide its politically charged story

This spring, Hulu’s premiering two dramas that explore the oft-fraught relationship between (patriarchal) society and women’s bodies. An adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale will be out in April, when we’ll all surely shake our heads over the dystopian novel’s prescience. But first, the original drama Harlots—a joint venture with ITV—takes us back to a time when an estimated 20 percent of women in London were sex workers, and a full 100 percent of them were expected to feel ashamed about that. That disapproval wasn’t to be aimed at a world that denied women education and advancement, but rather, the women who had the audacity to not lie down in the gutter and die.

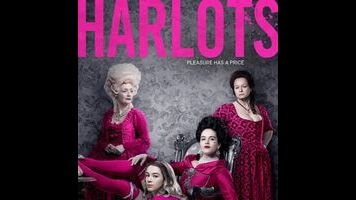

But a morality play this isn’t—Harlots may feature characters who are deemed sinners and those who presume to be saints, but they regularly switch positions, rendering any judgment moot. Series creators Moira Buffini and Alison Newman have combined their prestige drama and soap opera sensibilities to produce a scintillating confection, one that’s distractingly pretty and frequently gripping. The show’s sexual politics are on full display along with all the heaving bosoms and quivering buttocks. Its story centers on women, with men really only showing up to make trouble. A power struggle between two madams, played by Samantha Morton and Lesley Manville, is at the center of all the corsetry and intrigue. While their feud encapsulates the moral and economical debates, there are several side stories that offer rich opportunities for the rest of the cast, which includes Downton Abbey’s Jessica Brown Findlay.

Margaret Wells (Morton) is presented as the more sympathetic of the two rivals, who is to be commended for her enterprising nature: she was essentially sold into the sex trade at the age of 10, and now she’s running a “boarding house” of her own. As she tells her lover, “This city is made of our flesh—every beam, every brick. We’ll have our piece of it.” At first glance, that determination is laudable; Margaret refused to be beaten by a system that assigned her next to no value at birth, then promptly put a price tag on her prepubescent body. But while she may be affectionate with the women she employs, she remains their pimp. Her moral quandary is further complicated by the fact that she pushed her eldest daughter Charlotte (Findlay) into the courtesan life, and is already plotting her young daughter Lucy’s (Eloise Smyth) debut.

Morton’s performance, which is built on Margaret’s shaky moral ground, anchors the series. She’s tasked with taking a perverse pride in her daughters’ aptitude for the life they’ve been resigned to. The Oscar-nominated actor rises to the challenge, displaying vulnerability along with shrewdness, and crafting a complex character that we might even call an antihero. Margaret’s charming and caring, but she’s also all too aware of her standing in life. She’s bent on financial independence, and she’ll use any means to achieve it. The hypocrisy of using her own daughters to get there is lost on Margaret, but when you consider the even grimmer alternatives, it’s hard to judge her.

Even as it acknowledges that Margaret’s largesse doesn’t come without strings, Harlots suggests there are worse things, including being a prostitute without protection (contraceptive and otherwise), or working for the other madam in town, Lydia Quigley (Lesley Manville). Lydia offers a gilded cage, where the demands are higher, and her regard for her “girls” is considerably lower. But Harlots wisely avoids declaring a winner, preferring to leave black and white off its palette of rich, saturated colors. The two madams clash over customers and management styles, but they also share a complicated history, as well as a common enemy. Their relative success remains out of reach or an illusion, thanks to confounding laws—prostitution itself wasn’t illegal, but its places of business were—a growing evangelical movement, and a hypocritical clientele.

The first two episodes effectively set up the larger conflict that’s brewing, but they also revel in the colorful cast. Manville builds Lydia’s icy exterior only to have it melt away at the first sign of real competition from Margaret. Findlay’s character is a far cry from Lady Sybil; though she’s one of the most desired courtesans, Charlotte refuses to be at the whims of any man, even one who pays her gambling debts. And though she’s just now getting into the family business, Smyth’s Lucy displays an impishness that suggests she’ll soon be giving Charlotte a run for her money. But the show belongs to Morton, who plays the bawd, mother, entrepreneur, and second-class citizen with equal vigor and humor.

Reviews by Genevieve Valentine will run weekly.