As a director, screenwriter, and workaday creator of music videos and performance projects, Harmony Korine has developed an aesthetic as unique and bracing as any that have stemmed from the heyday of American independent film in the 1990s. He made his name in 1995 as the screenwriter of the nihilistic-teen movie Kids, but his own style—marked by a teeming mix of transgressive prurience and humanistic ideals—came into its own in his 1997 directorial debut, Gummo. (Reactions were mixed: Werner Herzog called Korine "the future of American cinema," while others proved considerably less charitable.) After his 1999 film Julien Donkey-Boy, concocted according to the rules of the era's purist Dogme manifesto, Korine fell out during a long period dotted by sporadic short works and troubling tales of druggy self-destruction. Now he's back, in a clear-headed fashion, with Mister Lonely, a new film featuring twin stories about celebrity impersonators and nuns. The A.V. Club recently talked to Korine about dancing, Buster Keaton, and blue-robed sisters flying through the sky.

AVC: Does an interest in vaudeville inform your work still?

HK: Yeah! That's my favorite. That was how I started. I never cared about making one coherent masterpiece with a conventional narrative. I always wanted my movies to have images falling from all directions in a vaudevillian way. If you didn't like what was happening in one scene, you could just snooze through it until the next scene. That was the thing about vaudeville: You didn't have to worry about the beginning and ends of these things.

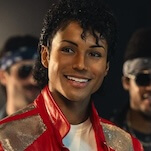

AVC: In Mister Lonely, Denis Lavant plays a Charlie Chaplin impersonator, even though you've said he reminds you so much of Buster Keaton. Why Chaplin instead of Keaton in the film?

HK: I was going to go with Keaton, because I prefer him. I love them both, but Keaton is my favorite. But that's why I didn't choose him. I loved him so much, I didn't want to work with him. This was as close as I was going to get to work with James Dean or Sammy Davis Jr. or the Three Stooges, but I never wanted to work with Keaton, because I couldn't ever direct Keaton. It would have been too confusing for me.

AVC: How do you regard the difference between the two of them?

HK: Keaton does a comedy of sadness. In close-ups on Keaton's face, there was true poetry. I always felt sort of guilty laughing at him. I always felt sympathetic. Chaplin was an unabashed human—he was just funny, not thinking about "The Tramp" too much. But with Keaton, there was something deep, like "the truth" in his face.

AVC: How did you go about assembling a cast from your fantasies of entertainers past?

HK: I was writing with my brother. We would eat chicken McNuggets and just sit there and talk about the criteria. They had to be iconic. They had to have a certain kind of mythology that we could bleed into the narrative. And then there were people I just liked. I liked the way they looked. I didn't want to have a fat Elvis in my movie.

AVC: What was the genesis for the idea?

HK: At first, it started with the nuns. I had these ideas for years, of images of nuns jumping out of airplanes without parachutes, and riding bicycles. I was also thinking about impersonators, and though these two ideas seemed separate, they spoke to each other. There was an allegory of sorts. Sometimes I just sit on the couch, and if I look out the window and see a fat guy with bloody knuckles and curlers in his hair spitting, I start to think, "Wow, what does that guy do for a living? What do his kids look like?" It just happens like that.

AVC: What did your brother bring to the movie?

HK: I felt like this movie had to be a little more conventional in the way it was told, and he is slightly more bookish than I am. He has a firm grasp of traditional elements of storytelling that I try to throw away. I felt like I needed someone who could rope me in a little bit. Also, I hadn't written in a really long time, so I didn't even know if I could write any more. I needed someone to bounce ideas off.

AVC: What feeling did you start to recognize when you realized you wanted to make a movie again?

HK: I don't know. I had traveled for so long, living like a tramp, and it just felt right. I started to think clearly again, and I couldn't really do much else. I tried working odd jobs that had nothing to do with creating, and it was difficult for me. In the end, I just always loved movies. When I'm making a film I feel most alive, like I'm doing the right thing, and I'm in the place where I need to be. But it was a struggle, and I wasn't sure if people would let me make films again.

AVC: What kind of odd jobs did you work?

HK: I worked at the Jewish community center in Nashville. I was a lifeguard's assistant. I worked as a shoe cobbler, did some yard work, worked with some Mexicans in the neighborhood, went to Panama where my parents were living and spent time with a group of fishermen…

AVC: What does a lifeguard's "assistant" do?

HK: Just watch the lifeguard. [Laughs.] It's the same as a lifeguard, but there's only one main lifeguard. He can't be expected to save everyone!

AVC: You've published a novel, A Crackup At The Race Riots. Before you decided you wanted to make another movie, were you writing in any other capacity?

HK: No. I would scribble shit and throw stuff down. I had houses that burnt down, so I lost a lot of things. After I had two houses burn down, it threw me for a whirl. I didn't know what I was doing. I didn't feel like I had anything to say. People everywhere were making movies or taking photographs and littering the world, and I didn't want to contribute to the pollution. I thought the most noble thing in the world would be to just disappear.

AVC: Did it feel noble during any of that time?

HK: I don't know. That's something I never thought about.

AVC: The new movie runs two very distinct stories on parallel tracks throughout. Did anything surprise you about the way they fit together in the end?

HK: I always knew they were going to work together. There will always be people who require taking a leap of faith. I knew that would be a challenge for a certain portion of people watching the film, but it didn't make that much of a difference to me. I felt like they were the same story and spoke to the same ideas. Ideas of faith and hope and—I don't want to say "magic," but there is something… They're all dreamers. I've always been pulled toward people who can't seem to make anything fit. It's like a cinema of isolation, of loneliness. They go outside the system and create their own society to develop their obsession to an insane degree.

AVC: The making of the movie involved immersive stays in a commune-like setting with the cast of characters you'd chosen. Once you've created a world like that to live and play in, is it difficult to leave to make sense of it and edit?

HK: Yeah, it takes a little while. You have to step back. But editing is fun for me. That's where you make things happen. Filming a movie, I just try to set things up and see where it goes. Editing is a puzzle. I often don't even know what I'm trying to say. I'm just trying to make myself laugh. That's it. It's musical, or something.

AVC: How about the soundtrack—how was it working with Jason Spaceman and Sun City Girls?

HK: Great! Spaceman 3 was one of my favorite bands growing up, and Jason Spaceman is someone I got along well with. I always felt his music was like narcotic gospel—there's something very moody and ethereal about it. Sun City Girls is the same, but different. To me, they're like the premier American avant music act. They're like the Marx brothers of music. I don't mean they're funny like that, but they turn everything on its head. I've been a fan of theirs for a really long time.

AVC: How did the interaction with those guys go?

HK: With Sun City Girls, I gave them the script beforehand. I just told them to create music based on the vibe of the story and the script. There were specific songs I sometimes asked them to do, or sometimes I would show them a scene, but mostly I didn't show them anything. Most of the time, they were making music based on the idea of the film before they had seen it. With Jason, we asked him to score specific parts of the film. When I was in the UK editing, Sun City was in America, so we worked through the mail. And Jason would go off to Wales for a week to a recording studio and then send mp3s. We would try things. Certain things would work; other things wouldn't.

AVC: Was there any interesting stuff that didn't work?

HK: That's always the case. It's something I can never figure out. A lot of times you can write a scene with a specific song in mind, and then you lay it over the image, and it kills it. I can never figure out why certain music works. Some music you listen to and say, "Man, that would be great for a movie." But when you try it, it's horrible, because the music itself is cinematic. The weight of it kills the image. Then there are things that work perfectly, like the Bobby Vinton song "Mr. Lonely." I was eating barbecue at this little restaurant and that song came on. The song itself was such a great narrative, this over-the-top, melodramatic narrative. I was like, "I want to put this in a film!"

AVC: Werner Herzog plays a role in this movie, as he did in your last one. What do you like about Herzog as an actor?

HK: I like working with family and friends and people I admire. All my movies are filled with family members of some capacity. I think it means more when you have a personal relationship with someone. Werner has a real charisma, and he has a deep understanding of entertainment.

AVC: What is his presence like? Do you talk to him about your role as a director?

HK: No. It's more about him talking about buzzards in the sky. [Adopts German accent.] "Oh, look at the buzzards in the sky. This is going to be a great day." That's the extent of it.

AVC: How about the footage of the nuns in the air? How did the filming of that work?

HK: It was a challenge. I wasn't in the air. I was on the ground trying to coordinate it, and it was tough. That's all I can say. There was only one place in the world that would allow a nun to ride out of an airplane on a bicycle, this one place in Spain. And when we went, it was like 140 degrees. I was hallucinating. The camera guy had a camera on a helmet, and he'd jump out at the same time, and I remember all we had to eat there were these four-cheese pizzas. After the third day being 140 degrees and all you were eating was four-cheese pizza, it took on this surreal quality, watching nuns jump out of planes without parachutes.

AVC: Did you ever have a desire to jump yourself?

HK: I was going to, because I was asking these other people to do it and I thought it would be fair, but my wife was like, "Forget it!"

AVC: Gummo had a thread of tenderness that seemed to go unnoticed in a lot of negative reviews, while Mister Lonely seems intent on making that aspect of the story much clearer and bolder. Were you trying to communicate differently this time out?

HK: I guess all films reflect your mental state at the time of making them. I wasn't trying to make a more commercial film. I just felt like this was the story I wanted to make. I felt like the characters would be fun to make, and it was reflective of my feelings toward the world. A long time ago, I gave up trying to figure out how people would react to things, or how I would fit in. I was always wrong. I always thought I would make a movie as successful as The Shawshank Redemption. I thought Gummo would be played in shopping malls. So I just stopped thinking about it.

AVC: Now that it's done, how do you feel about having made a movie again, after so much time away?

HK: For me, it's kind of like vomiting. Not that film is like vomit, but more like this mass of ideas and thoughts that you have and just have to put them out there. It's not even about making perfect sense—it's more about making perfect nonsense. I don't do too much soul-searching or self-analysis. I just enjoy making things.