Dogs can’t act. Apologies to the many great “animal actors” of Hollywood, but they can’t. That’s okay—they have other skill sets, and it doesn’t take much to make watching a dog entertaining. Filmmakers have relied on well-trained pooches and careful editing to craft canine-centric narratives (the Lassie approach) or called on actors to give voice to the inner emotional lives of their non-human protagonists (the Homeward Bound method). They have also, of course, turned to animation: Not only can the dogs of Oliver And Company act, they can also sing, dance, and do stunts!

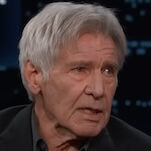

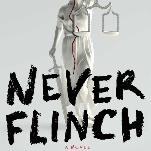

The latest adaptation of Jack London’s 1903 novel The Call Of The Wild opts for the animated approach—there’s no singing, but it seems stunts were a must. Yet its producers were not content to simply create a dog protagonist unfettered by the limits of real-life canine actors. This version of Buck had to look like the real thing, as real as a grumpy and sumptuously bearded Harrison Ford; they wanted the endless possibility offered by an animated dog, but also the heightened thrills and fears of seeing that dog roam a world that is recognizably our own. The resulting hybrid of live-action and photorealistic animation is perhaps the best that could be hoped for from a film trying to be two things at once. The promise of an adaptation of The Call Of The Wild in which the dog’s journey and emotional life take priority may not be fulfilled, but neither is the nightmare of more than 90 minutes spent watching Harrison Ford navigate a very snowy uncanny valley. It is neither disaster nor dream, landing firmly somewhere in the disappointing middle.

Like most adaptations of London’s novel, this version from screenwriter Michael Green hews loosely to the source material. Buck (animated, though played on-set by motion capture performer Terry Notary) lives a cosseted life in the household of a wealthy judge (Bradley Whitford), but his wilder instincts keep getting in the way. When a misadventure with a birthday feast condemns him to a night on the porch, he’s lured away from home by a dognapper who promptly ships him off to the Yukon, there to be sold to anyone in need of a very large sled dog. Buck is violently introduced to what London called “the law of club and fang” before finding himself on the sled team of two kindly postal workers (Omar Sy and Cara Gee); when they’re forced to sell the team, Buck and his new canine pals are suddenly at the mercy of a cruel, foolish would-be prospector (Dan Stevens). But between adventures, Buck keeps crossing paths with two entities that ultimately shape his future: the quiet, curmudgeonly John Thorton (Harrison Ford), and an unearthly lupine spirit with glowing eyes and billowing fur, which seems to guide him as, say, his own animal instincts might.

While inserting a great wolf spirit as the personification of the title may not be a particularly subtle choice, it’s an effective one, if only because it has no fealty to realism. Director Chris Sanders, best known for his work directing animated films like How To Train Your Dragon and co-scripting the 1994 The Lion King among other Disney classics, excels when The Call Of The Wild departs the realm of what’s possible in live-action, embracing all the possibilities that animation offers, including thrilling sprints through caverns of ice. This time spent with Buck does sometimes wander into the uncanny valley, but it’s less off-putting than you might suspect; the power struggles, adventures, and daring deeds rely so much on the physicality of all the animals involved that Buck’s too-expressive face doesn’t matter so much. In these sequences, the potential of the format is realized: The world still looks and feels like our own, but the story is one that simply couldn’t be told with animal actors.

It’s when humans enter the picture that things go sideways. It’s not as though the performances are bad, exactly, though one wonders why Sanders and company opted to bring in actors like Whitford for roles that could charitably be described as thankless. Ford and his beard have the meatiest material with which to work, as Green gives Thornton a more intimate, mournful backstory which ultimately makes his need as great as Buck’s. Gee and Sy fare nearly as well in the film’s most effective act, but Stevens, outfitted in a fabulous and impractical red suit, seems to have wandered in from another, far weirder film; he’s one mustache-twist away from Snidely Whiplash territory, a choice far more cartoonish than any of the film’s actually animated sequences.

Even if Stevens had both feet in this movie, however, there would be no denying that the experiment simply doesn’t work. It’s one thing when Buck races through the snow with his fellow dogs, or cavorts in the woods with the wolves he encounters along the way; it’s quite another when he plops down next to Harrison Ford, just in time for a nice long one-sided conversation about grief or alcohol or the wild and its call. Sure, the blended format makes it possible for Buck to stage a dog intervention in which Thornton’s stash of booze is confiscated, but just because it’s possible doesn’t mean it’s a good idea, and the film never quite recovers from the empty silliness of such sequences. London’s story is one of instinct and adventure in the great unknown. The tale Sanders tells is far too manicured and polished to measure up. Buck may thrive in the wilderness, but The Call Of The Wild wouldn’t last a day.