Before he began writing fiction in the late 1970s, the Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami was the owner of a jazz club in Tokyo called Peter Cat, which he finally closed shortly before the publication of A Wild Sheep Chase. It was around this time that Murakami took up marathon running, a subject he would eventually tackle in the essayistic memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, published in English in 2008. One is inclined to think of Absolutely On Music: Conversations, which deals mostly with concert music, as something of a companion piece to that most recent foray into non-fiction. Like What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, it shows Murakami’s gift for writing about a subject unpretentiously, but in detail, betraying its enthusiasm only through the act of writing.

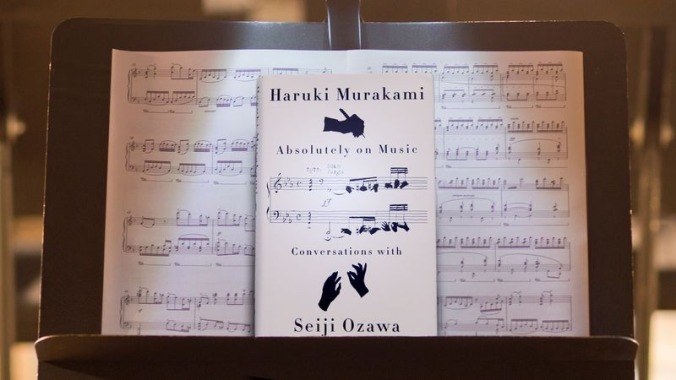

Murakami doesn’t make himself the central character of the book. Instead, his focus is on Seiji Ozawa, the storied octogenarian conductor best known for his long tenure with the Boston Symphony. As he explains in the introduction, Murakami first got to know Ozawa socially during a writer-in-residence stint at Tufts University in the 1990s, but it wasn’t until the maestro (as Murakami prefers to call him) underwent treatment for esophageal cancer that the two had a serious conversation about music. Absolutely On Music is structured around six of these, recorded in 2010 and 2011 at Murakami’s home and office or while traveling.

In the first, which runs more than 60 pages, they listen to and critique different recordings of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto, No. 3; others are devoted to subjects like opera and Gustav Mahler. There are names and dates sprinkled over every page Absolutely On Music, and yet it’s not a niche text. It’s not exactly an interview book, either, even if it composed mostly of these extended conversations (complete with time codes for the recordings under discussion) and shorter “interlude” interviews on topics like record collecting and the Chicago blues scene of the 1960s. Rather, Murakami, the self-described “amateur,” is using Ozawa’s first-hand knowledge of classical music and his effortless recall of soloists, performances, and moments as the counterpoint through which he can weave his own lifelong obsession with music, which he first describes as “a stimulus.”

In his fiction, Murakami has often written characters who see their lives narrowly, through their own fascinations (evident even in the titles of some of his novels, like Pinball, 1973 and Norwegian Wood), and he makes no secret of the fact that he himself sees everything as a writer. But his conception of writing as a unifying activity—one that is private, but public in its results, sustained by the paradoxical relationship between strenuous routine and imagination—is always compelling. Full of stories and opinionated asides, Absolutely On Music makes for a useful guide to the nitty-gritty of concert music for the uninitiated; its devotes pages to discussing differences in tempo between recordings of the same concerto, the evolution of studio recording techniques, and how a composer (in this case Brahms) can create the illusion of a brass or woodwind instrument playing continuously without a pause for breath. But it is also, on a subtler level, about the way the concert hall’s values of composition and rhythm can apply to any kind of creative life.

Purchasing Absolutely On Music via Amazon helps support The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.