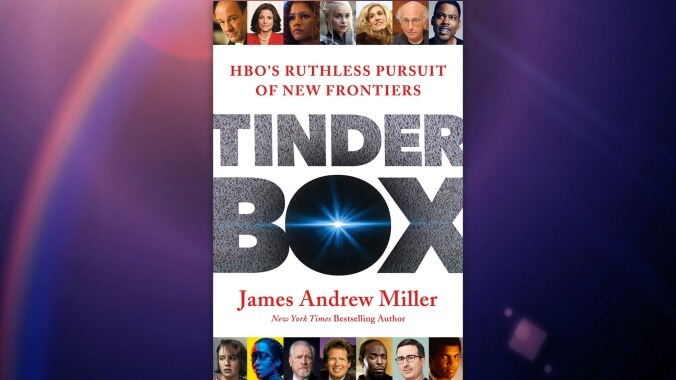

HBO oral history Tinderbox offers little more than amusing anecdotes

James Andrew Miller interviews dozens of key players from HBO’s past for his 1,024-page book, but can’t weave them into a cohesive whole

The HBO series Vinyl seemed destined for success. Created by Martin Scorsese, Mick Jagger, and Terence Winter (who’d served as executive producer of The Sopranos and creator of Boardwalk Empire), the 2016 show centered on the exploits of a 1970s record executive. The pilot was directed by Scorsese. Its cast wasn’t star-studded in the same way a series like Big Little Lies’ was, but Bobby Cannavale, Olivia Wilde, and Ray Romano weren’t nobodies. Yet Vinyl failed. Why did it fail? That depends on who you ask, but nobody disagrees. It failed.

The lesson that Casey Bloys, the current content chief at HBO and HBO Max, took from the experience was “there’s nobody above the law, there’s nobody who can’t make a bad show.” Even with all the right tools, sometimes you can’t create something worthwhile. A useful way, perhaps, of thinking about Tinderbox, an oral history of HBO from journalist James Andrew Miller, whose previous subjects have included ESPN and Saturday Night Live.

The massive, 1,024-page book is built on interviews of dozens and dozens of key players in HBO’s past. There’s Edie Falco and Laura Dern. Davids Chase, Simon, and Larry. There’s executive after executive after executive. Miller did an exceptional job getting important people on the record and at length.

That, unfortunately, is only half the job, and often the better you are at it, the harder the other half of the job—putting the book together in a cohesive way—gets. There is so much ground to cover, from 1971 to the present day. Organizing it all so that it flows well and gives readers the context they need is a gargantuan task, and Tinderbox doesn’t come close to fulfilling it.

There are a number of amusing stories for fans of HBO’s biggest hits. A standout is J.B. Smoove’s account of his Curb Your Enthusiasm audition. He recalls walking in and saying, “Okay, Larry, let’s do this baby, and since this is improv, I might fuck around and slap you in the face.” But that story is quickly followed by a section that exemplifies the book’s flaws.

Less than a page later, there’s a quote from John McEnroe about his appearance on the show. “When I saw the outline, I thought, ‘How the hell can somebody even come up with this? This guy’s out of his mind.’” That is immediately followed by bolded, italicized transitional text about a former executive returning to the HBO building because they were naming a theater after him. If you’ve never seen Curb or perhaps don’t remember the plot of a television episode that came out 14 years ago, Miller won’t help you. He never explains it.

This quick gloss is not in exchange for depth in other areas. Little in this book rises above the level of trivia. Did Michael Imperioli have a driver’s license when he started on The Sopranos? He did not. Tom McCarthy, writer and director of Spotlight, directed an unaired Game Of Thrones pilot. It never saw daylight because it was, apparently, horrible. But there’s little more detail than that.

The book is most engaging when it reveals the odd way executives think about the art of television. One example: In the late ’90s, HBO was developing a movie about the slave ship Amistad at the same time Steven Spielberg was developing his own. Because HBO was on track to release its film first, Jeffrey Katzenberg, then head of DreamWorks, called and asked new CEO Jeff Bewkes if HBO would drop the project to make way for Spielberg. Bewkes was hoping HBO’s version would compete for an Emmy, but recalls thinking, “If Steven thinks he can do for civil rights with Amistad what he did for anti-Semitism with Schindler’s List, we should hold back with our modest megaphone.” It’s got a nice ring to it, though it’s unclear just what he thinks Schindler’s List did for anti-Semitism or how Amistad could do the same for civil rights.

A more sinister turn occurs during the making of Westworld. Miller writes that creators Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan encountered resistance on one particular artistic decision: putting “faces in the foreground of scenes involving nudity.” Instead, “HBO would push back, asking for closeups of breasts and other body parts.” Worse, on a conference call, “an executive accused Joy of having a ‘girlish’ fantasy about how great ‘gentle sex’ could be.” This incident gets the rare-in-Tinderbox treatment of anonymizing both Miller’s source(s) and who that source was talking about.

An odd feeling builds throughout the book that Miller is protecting certain executives and the myth of HBO more generally. He tells the story of Chris Albrecht, the chairman of HBO who lost his job in 2007 after he was arrested for grabbing his girlfriend by the wrist and throat in Las Vegas. In the wake of this news, the Los Angeles Times reported that this wasn’t his first alleged offense: In 1991 HBO had paid a $400,000 settlement to a subordinate with whom Albrecht was “romantically involved” because he allegedly shoved and choked her. That chapter ends with a chorus of his colleagues opining about how everyone makes mistakes. Later, Miller refers to it as that “crazy night in Las Vegas.”

Similarly curious is Miller’s presentation of an instance regarding then-chairman Michael Fuchs’ decision to fire Bridget Potter, a senior vice-president. Then-HR chief Shelley Fischel said, “There have been instances when I believe HBO terminated women in a way that reflected a male perspective on employment… For women, Michael was not easy to work for.” The only follow-up to this is Potter calling Fuchs “an equal opportunity bully.” There is no way to know the reason for the absence of further comment. Did nobody have anything else to say? Did Miller not ask, or did he just leave it out?

Here, the overall surface-level nature of Tinderbox is a mark in Miller’s defense; he skimps on details everywhere, not just on workplace discrimination and sexism. At least his interviews have produced a nice volume of anecdotes to share at parties.