HBO reclaims its true-crime crown with 5 tales of murder, mayhem, and mystery

Next to its streaming competitors, HBO is a dinosaur. The original pay-cable network will celebrate its 50th anniversary in 2022, five decades in which it’s built a reputation—well, for many things, including hard-hitting true crime documentaries like Paradise Lost (1996) and The Iceman Tapes (1992), films that are less stodgy than PBS and more detailed (and graphic) than an episode of Dateline. (Reruns of Autopsy, anyone?) Of course, the cord-cutting era has upended these dynamics, leaving everyone—even HBO—scrambling to catch up to Netflix and its string of 2010s docuseries hits.

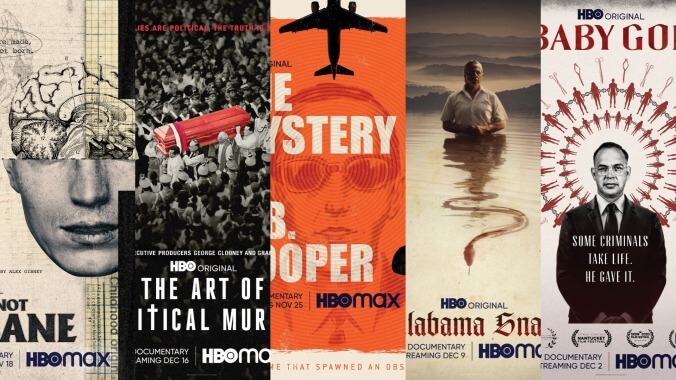

Beginning November 18, the network is reasserting its dominance with a series of five films that have only two things in common: High production values, and tales of real-life violence and mayhem. Some are serious and straightforward, and some cinematic and speculative. Some search for answers, and some recount the details for posterity. Some, to be honest, are more entertaining than others. But all of them come burnished to a high shine with that HBO prestige gloss.

The highest profile of the five was also the first to debut: Crazy, Not Insane (November 18, B-) is the latest film from the prolific Alex Gibney, who just last year brought the Elizabeth Holmes doc, The Inventor: Out For Blood In Silicon Valley, to HBO. (He also directed the two-part series Agents Of Chaos, which debuted on HBO Max in September.) Gibney’s made a series of documentaries dealing with faith for HBO, and in a way Crazy, Not Insane is part of this legacy, dealing as it does with a person—pioneering psychiatrist Dorothy Otnow Lewis—whose unwavering belief in her methods may have blinkered her as much as helped her. The belief in question here is Lewis’ research on Dissociative Identity Disorder, the controversial diagnosis formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder and popularized in pop-culture artifacts like Sybil and M. Night Shyamalan’s Split.

Crazy, Not Insane is presented in a “from the case files of” sort of format, as Lewis and her son go through reams of paperwork and handwritten notes from Lewis’ career as a forensic psychiatrist and expert witness. She’s an extremely empathetic woman, so much of that testimony has been on behalf of the defense: Lewis has interviewed 22 serial killers, by her own recounting, and has argued in court for many of them to be sent to mental hospitals rather than prison—or, at the very least, to be spared the death penalty. Famous patients include Genesee River Killer Arthur Shawcross, a case Lewis looks back on with regret and ambivalence, and a final pre-execution interview with Ted Bundy, who Lewis believes suffered from an undiagnosed case of DID brought on by his incestuous childhood.

Gibney is clearly fond of Lewis, and her sweet-natured credulity does contrast endearingly with the dark fascination of her work. But if one did not take the time to google “DID” after watching the film, one might come away with the impression that Lewis’ detractors are simply being punitive or envious, rather than rigorously scientific. It’s true that DID is more widely acknowledged as a credible disorder now than it was in Lewis’ ’90s heyday. But hypnotic regression similar to the type Lewis used in her work also fueled the Satanic Panic of the ’80s, in which innocent people had their lives and careers ruined—a rich vein of material Gibney ignores in favor of wry chuckles at a petite, sprightly woman delightedly recounting her interactions with the most violent men alive.

Lewis does not believe in the existence of biblical evil, and Crazy, Not Insane follows this line of logic by asserting that all so-called “evil” acts must have a biological and/or psychological explanation. It’s a fascinating idea, enhanced by some hair-raising interview footage that could make the most skeptical mind question whether there might be something to Lewis’ theories. The documentary also wisely avoids trying to out- Mindhunter Mindhunter by eschewing re-enactments entirely, relying instead on Laura Dern’s narration over illustrations of Lewis’ diary entries to weave together disparate footage. In the spirit of the scientific method, however, Crazy, Not Insane would stand on more solid ground if it gave more screen time to its critics.

A similarly enigmatic mystery drives The Mystery Of D.B. Cooper (B, November 25). The intrigue in this documentary is less morbid and more romantic: The perpetrator of America’s only unsolved skyjacking, D.B. Cooper became a folk hero for the cynical 1970s when he parachuted out of the back of a Boeing 727 with $200,000 in ransom money on November 24, 1971. No one knows what happened to him after that, or if he even survived the landing. But no one’s ever found the parachute, and although some of the cash washed up in rural Washington in 1980, D.B. Cooper himself has never surfaced, alive or dead. Did he leave the country? Blend back into society? Four different people claim, with unshakeable certainty, that they know who the real D.B. Cooper was, and all four of them sit in front of director John Dower’s camera for interviews.

This particular film comes from the Louis Theroux “sardonic Brit with ironic distance from the material” school of documentary filmmaking, and it does seem like Dower—who, predictably enough, co-wrote and directed Theroux’ 2015 film My Scientology Movie—is having a bit of fun with his subjects (regrettably so, in the case of a transphobic joke). And it is a wild tale, full of eccentric characters like the conspiracy theorist who lives in exactly the vintage RV piled with junk that you’d expect a guy who wrote a book called D.B. Cooper And The FBI to live in. There’s even a character who looks like Laura Palmer—or “the dead girl on the TV show,” as she calls her.

Unlike Crazy, Not Insane, The Mystery Of D.B. Cooper does rely on dramatizations to tie its story together, weaving them in with vintage 16mm footage that highlights just how different the world was in 1971, particularly in terms of air travel. Not only could you smoke on a plane—neither a security screening nor a photo ID was required to board a flight at that point in history. (Thus the frequent hijackings.) Of course, these differences weren’t all positive, as one subject reveals as she remembers the ad campaigns touting the sexual availability of flight attendants that were common when she began her career. They had gotten rid of the weigh-ins by 1971, she says, so things were a little better then than when she started in the ‘60s. And The Mystery Of D.B. Cooper is fueled by such wry observations, right up until an abrupt, but haunting, ending questioning the nature of belief itself.

Alabama Snake (B, December 9), meanwhile, takes the concept of dramatic re-enactments and applies a level of stylistic showmanship rarely seen in documentaries. This story is just as incredible as The Mystery Of D.B. Cooper, albeit with a more sobering outcome: Unlike the D.B. Cooper saga, here people actually got hurt. But Alabama Snake is still a whopper, told in the embellished style of old-timers spinning tales on a front porch. And that framing is appropriate, given that the credits say the film is “inspired by the work of” Dr. Thomas G. Burton, a retired English professor from East Tennessee State University who devoted his academic life to recording Appalachian folklore and culture, specifically the phenomenon of Pentecostal snake handling.

Set in the scrub-covered foothills of northern Alabama, this tale begins in a Piggly Wiggly parking lot and grows to a tale of fire and brimstone, of stubborn devils and guardian angels. Most of the film is devoted to the life of Glenn Summerford, a petty criminal-turned-Pentecostal minister who was either redeemed by the blood of Christ or used his religion as a cover for horrific abuse, depending on who you ask. Snake-handling services where believers drape themselves in rattlesnakes (if you don’t get bit, God is with you; if you do, you must have sinned, so no medical intervention is allowed) take place in isolated churches that are generally hostile to outsiders, which makes Burton’s trove of VHS footage from Summerford’s church invaluable to director Theo Love. And the ’80s aesthetics on display in the footage are liable to produce nervous laughter, if only for the contrast between the stiff Aqua Net hairdos and the mortal peril on display. The result is a story that seems to take place out of time, in a place that’s barely on the map as it is, and Love accentuates the mysticism as much as he can.

Alabama Snake is shot like a horror movie, and edited and scored like one as well: In one particularly ominous shot, Love cuts from a reenactment of Summerford “exorcising” a black, oily demon from a congregant to an eerie cackle over footage of an abandoned shack, as Summerford’s ex-wife Doris explains that fear is essential to the Pentecostal religion. These touches are undoubtedly cinematic, but they’re also leading, which may irk some documentary purists—particularly when Love interviews Darlene, the second Mrs. Summerford and the victim of the rattlesnake attack that anchors the story. She’s clearly a shattered person, which makes her mutterings about demons as the camera swooshes around her too uncomfortable to be rip-roaring fun. For the most part, however, Love’s stylization makes Alabama Snake stand out from the crowd.

Baby God (B, December 2), meanwhile, doesn’t have fun with its subject matter. But it’s difficult to find a lighthearted angle on this crushingly depressing story, even one that might be in bad taste. A sobering tale of medical hubris and the doctor/father/God complex of patriarchal medicine, Baby God tells the story of Dr. Quincy Fortier, who impregnated hundreds of women without their knowledge or consent over several decades as a fertility specialist in Las Vegas. Women would come to him for help getting pregnant, and would get results—but until the advent of DNA testing, what no one knew was that Fortier was inseminating these women with his own sperm. It’s a shocking violation, and an extremely intimate one: How can you put what’s essentially an act of sexual abuse behind you, when your abuser’s DNA is forever commingled with yours? And the dissociation of the victims interviewed in Baby God is tragic: They all say that they were raised to believe that a doctor was “like a priest” and should be obeyed without question, a haunting reminder of the arrogant dominion misogynistic doctors held over women’s bodies in midcentury America.

Director Hannah Olson uses bleakly beautiful shots of an abandoned clinic out in the Nevada desert to drive home the secrecy that surrounds Fortier and his crimes, a whisper network reminiscent of the truth seekers in Netflix’s The Keepers. And the mothers of these children aren’t Fortier’s only victims. Later on in the documentary, Baby God shifts to Fortier’s biological children, both the ones he acknowledged and the ones who found out about their parentage much later in their lives. “There’s this monster… he’s living in me,” one says; he’s haunted by the truth behind his conception, and comforted by seeking out his biological half-siblings in meetings that are part family reunion and part therapy. Stories like these are why 23andMe has you sign a waiver when you send in that tube of saliva, and after watching it, you’ll never think about those tests—or a trip to the gynecologist’s office—the same way again.

The last of HBO’s unofficial series of true-crime docs, The Art Of Political Murder (B-, December 16), is also the most conventional of the bunch. Bookending a run that began with Laura Dern narrating Dr. Dorothy Lewis’ diary entries, this film comes with a little celebrity wattage of its own in the form of executive producer George Clooney. And, as one might expect from a Clooney cosign, the film deals with human rights issues, specifically the genocide of Mayan people by the Guatemalan government from the early 1960s through the ’90s. If you need an introduction to the genocide for international audiences, however, The Art Of Political Murder isn’t it.

Instead, the film chronologically traces the 1998 murder of Guatemalan human rights activist Bishop Juan Gerardi from the night of his death through the verdict in his killers’ trial. The case had huge implications for Guatemalan politics, as interview subject after interview subject explains. But given that the Bishop’s death appears to be less emblematic of the genocide and more of a turning point in the conversation around it, simply viewing this documentary without previous knowledge of the massacres doesn’t resonate as well as it could. At times, it seems as if there’s a larger, more interesting story around the edges of director Paul Taylor’s rather dry, procedural approach—which might have its benefits, if it motivates viewers to learn more about the history of state-sponsored terror in the region. But despite the filmmakers’ efforts to shove this sprawling story into a true-crime box, ultimately it’s a bad fit for a series that’s more focused on chilling mysteries than cold historical facts.