Rolling Stone: Stories From The Edge is a bizarre documentary, especially considering it comes to us from Oscar-winning director Alex Gibney (co-directing with Emmy winner Blair Foster). Maybe the timing is suspect: As it celebrates its 50th anniversary, the magazine is currently up for sale, and a less-than-fawning biography of Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner has just been published (Joe Hagan’s Sticky Fingers). The magazine still clings to its print copies, which now have many fewer pages than they did in its heyday. Still, Rolling Stone’s significant stature in journalism history cannot be denied, and this four-hour HBO documentary seems like an attempt to remind everyone of that importance, as the magazine ascended from record reviews on newsprint to noteworthy interviews with presidents.

But it starts off in such a careening fashion. After a few notes about how Wenner and his then-wife Jane borrowed $7,500 to start the magazine in 1967 in San Francisco, the documentary immediately devolves into gratuitous naked-groupie footage (although at least now we know exactly how those famous plaster-casts are made). Ostensibly because this was Rolling Stone’s first significant story? It’s not really clear. It’s actually less clear when we go from Jefferson Airplane’s San Fran mansion to Ike and Tina Turner’s living room, to delve into a RS feature story on the couple. We’re left with a troubling quote by Tina that she has to do what Ike says, and then we’re on to the first of many John Lennon interviews. Sure, we know how Ike and Tina turn out, but the cuts are discordant enough to be jarring. There’s no narration to hold the overall through-line together, just quotes read out loud from the stories themselves (by actor Jeff Daniels). Even more frustrating are the brief glimpses of the offices filled with overflowing ashtrays, and the typewriters, and the galleys, laid out using rubber cement and X-Acto knives; since today’s publishing world is a far cry from all that, a closer look would have been welcome.

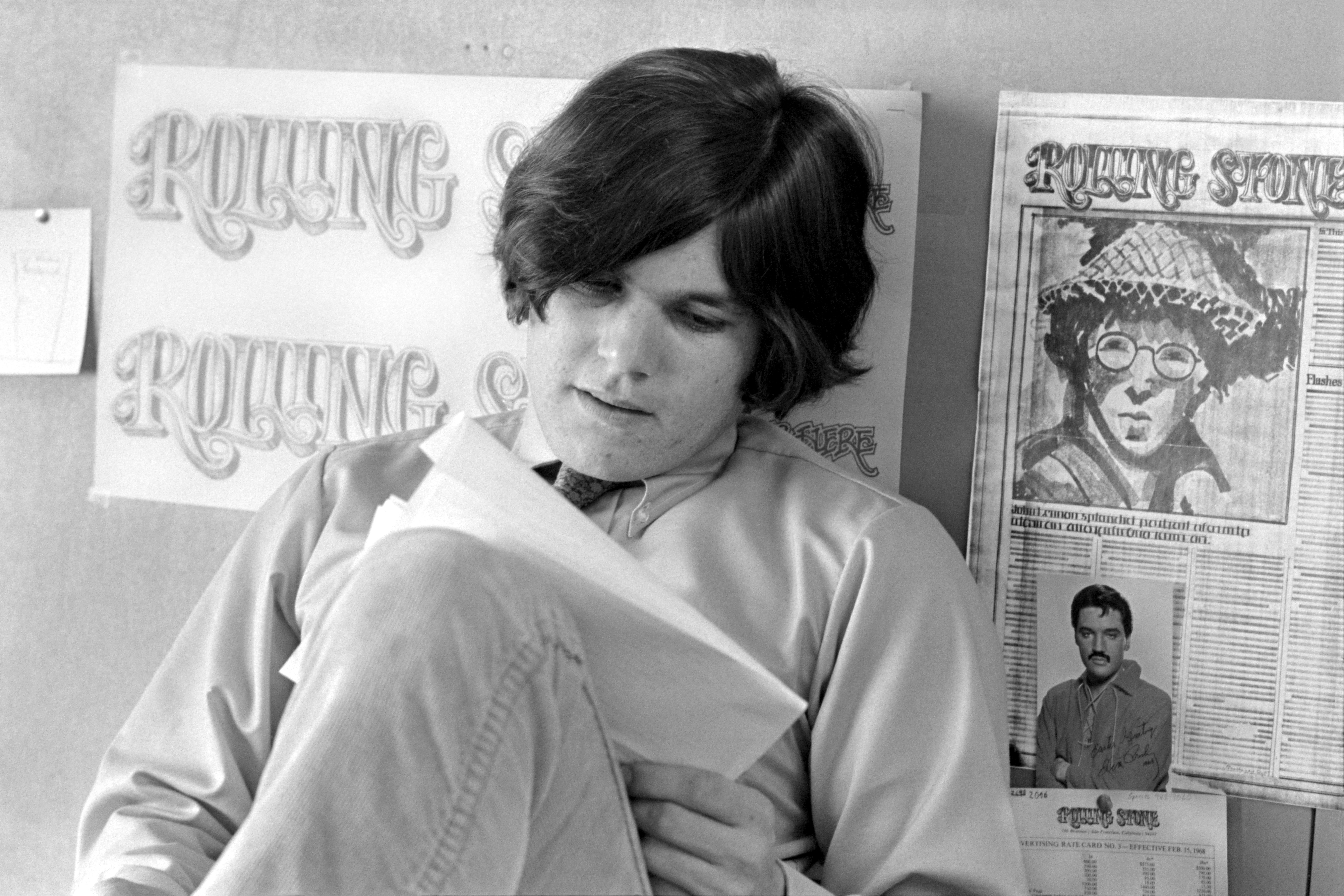

Instead, the documentary is eager to trace the success of everyone from Bruce Springsteen to The Clash directly back to Rolling Stone. Springsteen did invite RS writer Jon Landau into the studio with him after a thoughtful review that declared him the future of rock ’n’ roll, and Landau eventually became a music producer. Rolling Stone was also one of the first U.S. publications to cover The Clash. Best of all, there’s baby Cameron Crowe, cutting high school classes to go interview the likes of Deep Purple and Jethro Tull, for the real-life roots of his movie Almost Famous.

Wenner pops in and out through it all, sometimes walking through a gallery of some of his magazine’s most famous photos with photographer Annie Leibovitz. She recalls how nice John and Yoko were to her on her first shoot with them, and credits Wenner for sending in a young, untested female photographer. We also hear from famous RS luminaries like Hunter S. Thompson, trying his hardest to sway 1972 voters toward George McGovern, and to examine the depravity of Palm Beach in the Roxanne Pulitzer divorce case.

What’s interesting is how many of Rolling Stone’s most famous stories are not actually music-related: The documentary states that coverage of the Patty Hearst kidnapping case in 1974, thanks to an inside source, was the story that helped put Rolling Stone on the map, raising it from a counter-culture publication to a mainstream magazine. The documentary credits the magazine’s article on Jimmy Swaggart’s fall from grace as helping to stem the evangelist tide, in a segment about Swaggart that really seems to go on for too long.

Things do seem to pick up in part two of the documentary. We see the magazine struggle as the ’80s dawned, as the magazine’s now-ex-hippies moved from San Francisco to New York, and Wenner began to resemble no one as much as the establishment itself. As one of the writers points out, “no musical center existed in the ’80s,” so the magazine’s staff warred among themselves over how much to cover upcoming genres like punk, hip-hop, rap, and alternative in favor of Rolling Stone’s old bread-and-butter artists like Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones.

The hip-hop and rap section is one of the documentary’s most interesting because it contains a rare nugget of criticism, by writer Alan Light. He had devoted himself to covering albums by upcoming black artists like Public Enemy, only to see Nirvana make the elusive RS cover after a single hit song. Light became particularly close to Ice-T, who documents how he came up with his landmark and controversial song “Cop Killer,” leading to an Oprah showdown in which he successfully out-argues Tipper Gore. Ice-T admits here, “My mistake was thinking that I could say anything and there would be no repercussions.”

As the decades progress, the doc features Rolling Stone’s (sometimes incendiary) sitdowns with Bill Clinton, a candidate who seemed to the staff to manifest the idealism of the 1960s. RS writer Michael Hastings (who died in a car crash in 2013) is lauded for his takedown of U.S. General Stanley McChrystal in Afghanistan, possibly to offset the magazine’s ’90s dive into teenybopper pop like Britney Spears and ’N Sync.

But no event in Rolling Stone’s recent history stands out as much as the scandal over the 2015 story “A Rape On Campus” after it was discovered that the alleged victim, referred to as “Jackie” in the article, fabricated her story to writer Sabrina Rubin Erdely. Rolling Stone wound up printing multiple retractions to the story, and in 2016 a jury found the magazine and Erdely liable for defamation to the tune of $3 million in damages. It is a journalistic disaster that Wenner shrugs off as “once in 50 years,” citing “dumb fucking luck,” even as the story not only irrevocably damaged the reputation of the magazine, but made it even harder for sexual assault victims to come forward for fear that they would not be believed.

The HBO press release says that the documentary “is presented by HBO Documentary Films; A Jigsaw Production in association with Nevision Limited and Rolling Stone Productions,” which helps explain why it’s as fawning as it is. It especially stands out in contrast to one of the doc’s best moments, when a young Cameron Crowe gets called into Wenner’s San Francisco office to discuss a Led Zeppelin profile in which the band had taken over the narrative, offering little from the writer himself. That kind of even-handedness is something this documentary definitely could have used more of; instead, all we’re left with is the sense of how proud Rolling Stone is of Rolling Stone. That’s justified in many cases, but it still only displays one side of the story. Rolling Stone knows that better than any other magazine.