HBO’s Spielberg is a wide-ranging, but inessential portrait of one of America’s most popular artists

Edited from an unprecedented collection of talking-head interviews with the director and his friends, family, and creative collaborators, the new HBO documentary Spielberg offers a comprehensive career history of one of America’s defining popular artists. But what do its 145 minutes (an appropriately Spielberg-ian chunk of time) really tell us about Steven Spielberg, aside from the fact that the man has made a lot of movies? Not much. Even at his most thoughtful and challenging—in the likes of A.I.: Artificial Intelligence and Munich—Spielberg is mostly an intuitive artist, and his darkest pictures are nonetheless painted from an earnest, sentimental palette. Will anyone who’s seen E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Catch Me If You Can, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, etc. be surprised to learn that the director’s childhood was heavily affected by his parents’ divorce and the distance it created with his father? Will they be shocked to discover that the filmmaker behind Lincoln, Bridge Of Spies, and Amistad has strong, idealistic feelings about American values? Is anyone going to be blown away when they learn that Steven Spielberg—the Steven Spielberg—grew up in the suburbs and loved movies as a kid?

Of course not. Spielberg is a master of the obvious, and that’s exactly how director Susan Lacy chooses to present him in this documentary, which closely follows the formula of her long-running PBS series American Masters: plenty of journalistic access (including a once-in-a-lifetime roster of interviewees and plenty of vintage home-movie footage), but limited insight. Opening with a famous sequence from his favorite film, the David Lean epic Lawrence Of Arabia, it ostensibly tells the story of Spielberg’s development as an artist, though not always in chronological order, which yields some strange and clumsy results. For example, considering how often Spielberg references the director’s early life, the decision to not mention his Orthodox Jewish upbringing until the halfway point—that is, the part of the documentary that deals with Schindler’s List—is odd, nearly contradicting earlier sections.

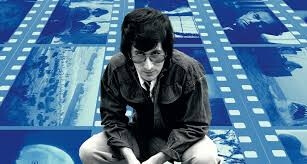

As for the real nuts-and-bolts of the artistry—say, what makes a Spielberg movie shot by Janusz Kamiński different from a Spielberg movie shot by Dean Cundey or Douglas Slocombe—forget about it. Movie directors are professional conversationalists; the job is mostly talk, every scene explained repeatedly from different angles to producers, crew, actors, and editors before it ends up on a screen. But the anecdotes told here are old chestnuts; one can only hear about Jaws’ malfunctioning animatronic shark so many times. (However, the story about how George Lucas re-wrote Star Wars’ opening crawl because Brian De Palma couldn’t understand the plot is vastly improved by Spielberg’s screeching, whiny, over-the-top impression of the latter.) The Super-8 footage of Spielberg and the other directors of his generation palling around in the 1970s is a minor treat for fans, but it would take an avant-garde artist to draw some insight out of these grainy shots of Lucas and Martin Scorsese nodding awkwardly at the camera from a dimly lit kitchen.

Thankfully, Spielberg, the father of the modern blockbuster, has made so many classics and huge hits that Lacy’s overview doesn’t have to uncritically fawn over every one of his movies to justify his genius. It’s somewhat refreshing to see a stolid, workmanlike profile acknowledge artistic shortcomings, or even to hear the director himself admit to chickening out when it came to sex in his adaptation of The Color Purple. And yet, Spielberg is such a known quantity that one almost wishes that this documentary had a contrarian streak, or at least tried to defend commercial and critical failures like 1941. At least then, it might offer something that hasn’t been said a thousand times before. In other words, one wishes that it had a point of view.