Helena Bonham Carter on playing eccentrics and having a baby with Elizabeth Taylor

In reprising her role as The Red Queen in Alice Through The Looking Glass, Helena Bonham Carter continues what’s been an award-winning career defined by an adeptness for portraying the eccentric. Though Bonham Carter’s capabilities certainly aren’t limited to those roles, having received an Oscar nomination for her role as Queen Elizabeth in The King’s Speech, the London native’s most comfortable form has come by way of uncomfortable characters.

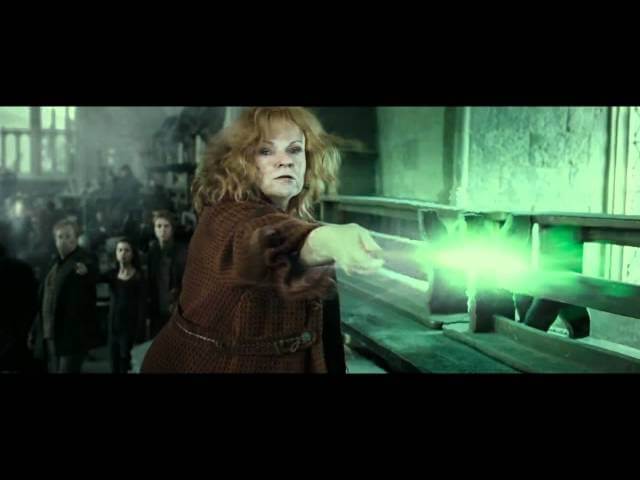

A living primer on how to emulate the bizarre in as many ways as possible, Bonham Carter’s versatile approach to what might otherwise be a phoned-in performance of “crazy” has lent a certain degree of individuality and nuance to such characters as everyone’s least favorite cousin Bellatrix Lestrange from the Harry Potter films, the perpetually jaded Miss Havisham from Great Expectations, or the chain-smoking disillusioned Marla Singer of Fight Club. In a conversation with The A.V. Club, Bonham Carter delved into her choice in roles and how much some of them stay with her.

The A.V. Club: You’ve played a lot of damaged characters.

Helena Bonham Carter: Yes. They’re damaged. Definitely damaged.

AVC: Thinking specifically about characters like The Red Queen or Bellatrix Lestrange, are you drawn to those types of roles?

HBC: I definitely like damaged people. I’ve got an affection for them. My mom’s a psychotherapist, and it’s always interesting to watch why people have developed the way they have. It’s a longer journey to work out, but there isn’t really a great scheme or conceptions that I make about playing them. It’s just like, “Oh yeah, I’ll do that.” It’s also about the kids and location, but also I was lucky because [the characters] come from two great authors. They both have the scope to invent stuff. I mean, Bellatrix I milked to the hilt because I was so bored. It was great doing Harry Potter because they really look after you, but you’re stuck in a trailer for hours, and it’s only one set, but I knew I had to do something that was visually catching in order to make the kids remember me. I was given the tipoff right from the start that [Bellatrix] was not a very significant part. [My daughter] said, “It’s not a big part, but it will be significant plot wise,” so I’ve got to work out how they’ll remember me. You have to make it fun, and I knew we had to bring energy. On a big CGI film, I felt a responsibility to be fully alive and bring some energy to the set, because you can get so infected by the laboriousness of getting a shot right. It takes so long, so I was just determined to bring some fun.

AVC: Is that historical stereotype of the “crazed woman” character something you take into account just for the sake of taking your roles beyond that?

HBC: I hadn’t been. But there have been many of those stereotypes. You’re right. I think that as an actor, I always feel responsible to be as precise as possible. There’s no plate. The more detail and the more specific and precise you are, then you’re not going to play a stereotype. You have to have respect for the character and be their champion. But a lot of it’s in the writing. You inherit somebody else’s work, and Linda [Woolverton, Alice screenwriter] did a great job. That’s what makes me go to work, because I can listen as a character. It’s on the page. All the complexities are there; it’s just up to you to examine it, hopefully, and question it. With something that offers you all of these different colors and choices, that’s what’s exciting. When it’s something where you really have to search around for a choice of what makes it work—just one way it works—that’s when it’s hard. But Linda was particularly idiomatic with these characters. You could recognize the Red Queen through the dialogue. She was written idiomatically, and so many scripts aren’t. And I think it helps being a woman. It’s a bit of a woman’s form, come to think of it. Between Alice, Linda, [and producers] Suzanne Todd and Jennifer Todd, there’s a bit of, not quite Whatever Happened To Baby Jane?, but…

AVC: It’s close.

HBC: [Laughs.] Yes. Very.

AVC: Do you make it a point to choose a character like The Red Queen just for the challenge of bringing depth to what’s essentially a caricature?

HBC: I try. That’s why I go to work. I don’t work all the time, also. I’ve got two young kids, so I try to make the most of it, and my work in a way is my play, as I try to explain to my children. [They say] “Why do you have to go to work? You don’t have to work,” and I say, “Well, no. I do. I have to work for me. It’s in my soul, because my work is like your playing.” So, for me to be satisfied and fulfilled, I’ve got to exhaust every possibility and to think about it and try everything and research and do everything, and I am pretty thorough. I don’t know that I’m always successful, but I’m very thorough, and I work hard. And I love people. Usually I fall in love with someone on the page, and I feel like it’d be great and try to have it and try to make them come alive in as many colors as possible.

AVC: Thinking about your real-life role as a parent, has that influenced your choice in roles or even your creative approach as an actor?

HBC: Not so much my choices but definitely in part, because a lot of the criteria for the job immediately changed. A lot of it went right out the window because the films were not shot in England. I don’t think I’ve shot anything away from them more than two weeks. The first Alice was shot in L.A., but we brought them with us because they were so young, so it didn’t really matter. So yeah, a lot of it depends on where it is and how big a part it is. Because of that a lot of them are more character parts and more manageable with big balance and a kind of juggling act.

AVC: Looking all the way back to the beginning of your career. I mean, not to sound like it’s that far back.

HBC: Oh, it is that far back. It’s okay. I’m proud of being around for so long. I survived. [Laughs.]

AVC: From the standpoint of personality, your characters have pretty much run the full gamut. Has that been a kind of personal benefit just in terms of keeping things interesting for you as an actor?

HBC: Well, I suppose my privilege is that I’ve been continually employed, but I’ve still got all these characters around inside me. So the biggest privilege for me is whenever I play somebody, I sometimes hope that I can still keep them with you. Like I played Elizabeth Taylor not that long ago, and she pops up. She had such huge strengths, and she can sometimes help me. I drop into her and her sense of humor, but I borrow. Sometimes when I’m in public, I drop into Queen Mother. She helps me because she was very expert at being gracious in public and slightly passive aggressive. [Laughs.] Not passive aggressive—she had real grace and knew how to have an armor, and she knew how to acknowledge every individual. So she helps me, too. So did Elizabeth [Taylor], of course. Elizabeth knew how to be famous. So all these different people that I’ve played, they help. I still carry them around, and that’s a big gift. I feel like on a personal level they’ve just enriched me, and it’s just been fun to know them. It’s like having all these new friends.

AVC: Do all of the characters stick with you like that?

HBC: They do, but not intentionally. It’s just a muscle memory effect. I’ve got a great friend who’s a voice actor, and he sometimes has to debrief me because sometimes the accent has stuck around way too long, and it’s very difficult to get rid of it. But they don’t necessarily stay intentionally. They just pop out. But they’ve always taught me stuff. The education that comes with the job has always been great, too. I’m about to play someone who’s mentally ill, is on several different medications, and has a slight learning disability, and I’m brimful of all that crap, and I see the world in a completely different perspective. You’re always doing that. You’re changing perspectives, and trying to see the world from their perspective and saying, “Well, if this were to happen to you, how would that change your day-to-day living? How would that change the way you see someone or experience something?” The young lady I’m about to play has got such physical damage from the side effects of her medication that a flight of stairs would be like an absolute Everest for her. It’s called 55 Steps, in fact, because something even that simple would be painful. We wouldn’t think of that, or I wouldn’t. Yet. [Laughs.] But that’s fascinating.

AVC: And that’s a biopic about Eleanor Riese?

HBC: Yes! That’s her.

AVC: Is there a different dynamic for you in portraying a real-life individual who’s troubled as opposed to a role based in fiction?

HBC: You have a responsibility when it’s somebody real. Definitely. But you sort of ask for their help, too. I might be totally bonkers, but I do believe that there is a spiritual element to it. Actually, I just played someone who’s still alive, Mary-Kary Wilmers in this television series called Love, Nina, and when I accepted the part I said, “I’ve got to have her blessing,” and she did [give it to me]. I explained to her, “I’m never gonna be you, but it’s gonna be as if you and me had a baby. What’s gonna come out?” It’s the same thing with Elizabeth Taylor. I could never be Elizabeth. It’s gonna be me and Elizabeth having a baby. With me and Eleanor, it’s the same. [Laughs.] I won’t be exactly how she was. No one knew her. Though the pressure is less than the Queen Mother and Elizabeth, I still have a responsibility, but it will be as if Eleanor and me had a baby. So it would be called “Helenor,” basically. In my head at least. God knows what’s gonna come out.