Helter Skelter is long on detail, short on insight

Towards the end of Helter Skelter, journalist Steve Oney says of Charles Manson and his so-called “family” of brainwashed burnouts, “the more you focus in, the less glamorous it becomes.” And at nearly six hours, this docuseries has the luxury of taking its time laying out the factors that led to the murders of nine people, masterminded by a diminutive wannabe pimp who just couldn’t accept that his songwriting was average at best. That’s two more hours than Netflix’s Conversations With A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, and the same length as cult documentary Wild Wild Country. Manson’s misogyny and notoriety are akin to that of the former, but the story as a whole is a lot like the latter, showing the slimy underbelly of a ’60s counterculture that preached freedom and acceptance while hanging onto patriarchy and white supremacy.

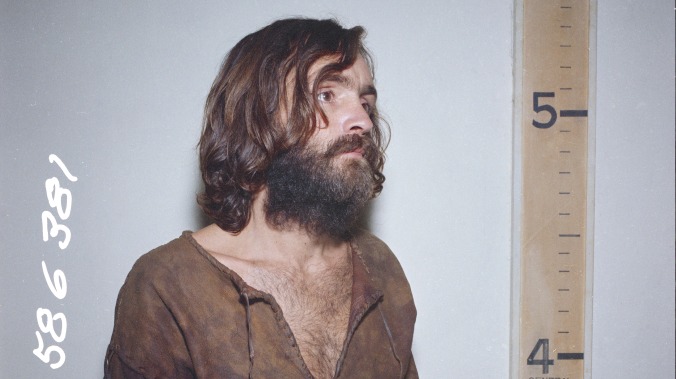

That particular point was fictionalized to thoughtful effect in Mary Harron’s 2019 film Charlie Says, and Helter Skelter covers a lot of the same material in terms of Manson’s sexual and emotional abuse of vulnerable teenagers, many of whom ran away to escape violence at home. Overall, the docuseries is quite sympathetic towards these women, who to be clear did experience horrific abuse during their time with the “family.” In terms of Manson himself—whose life story takes up two full episodes—the series falls on the “nurture” side of the “nature versus nurture” debate, as expressed through an acquaintance from his early years in small-town West Virginia who says Manson “wasn’t born evil.” An unstable childhood spent in and out of various institutions, she (and the series) argues, made him that way.

But two things can be true at the same time. Charles Manson may have been a product of the American penal system, but many people grow up under similar circumstances and don’t start deranged cults. Presenting Manson as a symptom of a diseased culture is where Helter Skelter indulges in some myth-making of its own, as well as in its frequent use of Manson’s music, sometimes accompanied by blurry re-enactments of women adoringly watching him play guitar—unintentionally hilarious, given how mediocre the music actually is. This portrait of the narcissist as misunderstood artist doesn’t jibe with interviews with record producer Terry Melcher, whose lack of interest in Manson’s music triggered a hissy fit of homicidal proportions. But it does align with how Manson liked to see himself, as reflected through interviews with victims/ex-followers who, despite everything, still speak fondly of the man.

Presumably, as with Wild Wild Country’s Ma Anand Sheela, the series’ on-camera interviews with these women were contingent on not pressing them too hard on sensitive topics. One former member complains that cops smashed her guitar when they came to arrest her compatriots, an anecdote that, even if you’re generally anti-police, can’t help but bring to mind a popular Kardashian-themed meme. It’s also frustrating to listen to interviews that downplay the racist paranoia behind “Helter Skelter,” which the documentary presents as a secondary motive that wasn’t actually all that important to the murders. That may be true, but does it justify the ease with which the “family” accepted Manson’s race-war vision? 50 years later, are they still under Manson’s spell?

Deglamorizing the “family” wouldn’t be necessary if Manson hadn’t been held up as a counterculture hero, both at the time of his trial and in the decades since. Many a high school had a goth kid who carried around a copy of Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry’s book Helter Skelter in the ’90s—at least, this writer’s high school did—and (male) reporters who worked the case describe him as a “philosopher” as well as a con artist. The fog of nostalgia that hangs over the ’60s is indeed thick, even when discussing the murders widely considered to have ruined everything. Again, the filmmakers don’t press too hard, allowing all but the “Helter Skelter” theory to pass by in conventional fashion.

Helter Skelter is full of detailed backstory and an impressively deep archive of vintage materials, everything from footage of Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski’s wedding reception to newspaper clippings jeeringly dubbing Manson’s mother Kathleen Maddox the “Ketchup Bottle Bandit” after a failed stick-up. This vintage footage adds visual interest and a sense of time and place to the story, with the side effect of making the production designer and casting director of Once Upon A Time…In Hollywood seem really good at their jobs. (Seriously, it’s eerie.)

The series’ structure, however, is not as impressive. The premiere is optional if you plan on watching the rest of the series, beginning with a standalone episode where Manson hanger-on Bobby Beausoleil describes the murder for which he is still serving time before backtracking to go entirely chronological for episodes two through six. Here, the execution is a little too thorough, repeating a substantial amount of footage as the saga as a whole catches up to that initial chapter. This repetition really stands out when you watch episodes of Helter Skelter back to back, but may not be as noticeable if you tune in week to week. Still, it’s indicative of this self-proclaimed final word on the Manson family’s greatest flaw—it’s so committed to detail, it forgets about insight.