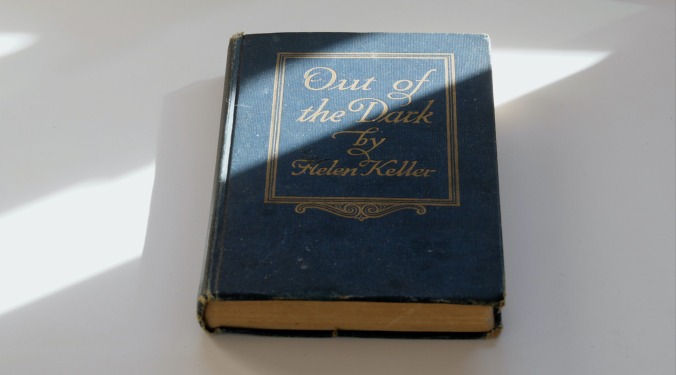

Much of Her Socialist Smile amounts to a chronology of Keller’s activism (largely narrated by the poet Carolyn Forché), and the film is highly engaging on this count. Gianvito’s impulse to defamiliarize, though, goes beyond an exposition of Keller’s political work, and is further reflected in the film’s scintillating form. Forché’s narration is sometimes accompanied by functional images, such as a shot of Keller’s 1913 book Out Of The Dark, which includes the essay “How I Became A Socialist.” More often, we get sensuous visuals—mostly landscapes and images of nature—that are not just counterintuitive but downright confounding in their apparent disconnect from the audio. In one of the film’s more unexpected juxtapositions, an account of Keller’s political reading, which included The Communist Manifesto and Mikhail Bakunin’s God And The State, arrives alongside a close-up of a slug.

On one level, these texturally specific images highlight the tactility that Keller would have been intimately familiar with but which cinema can only indirectly convey. On another, they remind us of the senses that she did not have access to, prompting us to consider how these condition our thinking in ways that we take for granted—and what it would mean for things to be otherwise. These questions emerge most forcefully in Gianvito’s treatment of her public speeches, of which no footage exists, despite scores of well-attended appearances. Gianvito’s “solution” is daring and inspired: Attempting to bring us closer to Keller’s experience, he presents her words in white text on a black background, with no sound.

Indeed, Her Socialist Smile is, in a very literal sense, a film to be read. This is a stark, provocative approach, one that doesn’t just confront our conventional notions of what is “cinematic,” but also asks what rhetoric and oratory mean to someone like Keller, who learned about the world through her fingers. Further, it suggests that she might even have been better equipped for being free from what contemporary media studies calls “visual culture.” We get a vivid sense of this when Gianvito presents a clip of Noam Chomsky speaking, where the effect of experiencing his speech cadences and body language, after so much onscreen text, is genuinely uncanny and hypnotic, practically hindering our ability to engage with his words. Another notable interlude, which puts Keller’s words in red text, accompanied by a blaring punk-rock anthem, makes a related point, highlighting the distracting audio-visual barrage of information we are confronted with on a daily basis.

Her Socialist Smile develops, in other words, a kind of ethics of the image. Gianvito is not, of course, suggesting that we should somehow give up our senses—only that, whatever the technology or medium we engage with, it is our responsibility keep our minds from becoming what Keller called “automatic machines.” A few times across the film, the director cuts to an empty theater, where we are presented, again via text, with some of Keller’s more memorable responses to interviews. (Q: “What do you think of Capitalism?” A: “I think it has outlived its usefulness.”) But the choice of location is pointed, for it shows that anything can, as it were, be turned into entertainment. However much we may agree with Keller’s responses, we also realize how easy it is to become overtaken by context—in this case, a kind of snappy, soundbite presentation—and thereby slip into an uncritical frame of mind.

When Keller’s contemporaneous commentators lambasted her for venturing into politics, they often did so on the condescending grounds that her limited experience of the physical world somehow negated her opinions on practical matters. While watching Her Socialist Smile, however, we confront the exact opposite conclusion: that Keller’s difference in abilities in fact strengthened her practical reason, enabling her to see more clearly with, as she phrased it, “the eyes of the mind.” It is a genuinely thought-provoking notion, suggesting that the work of building a better future starts with the imagination, the kind of vision available even to the blind. It would be misguided, though, to simply see Gianvito as forwarding a thesis about Keller. Rather, Her Socialist Smile conveys something deeper, more fundamental: that no matter what the medium or message, one must never forgo the responsibility to think.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.